There are many reasons for this continued improvement in yield: better genetics, equipment efficiency and speed, better timing and placement of seeds, fertility management, plant population increases and even plants that resist bugs and diseases.

In short, we do a better job of growing corn in differing soil types, varying weather and other environments today than we ever have before.

Corn plant breeders have actively bred corn plants for increased yield and agronomic performance for over 100 years. Advancements have been significant, as yields that averaged 35 to 40 bushels per acre in the 1930s are averaging over 150 bushels today.

In addition to plant selection, equipment technology has adapted to improve the seedbed and seedling placement. The timing and placement of fertilizers has challenged the plant to do more and sustain stress better than ever, and herbicides, insecticides, pesticides and fungicides are more easily applied. Perhaps the most obvious change over the years has been increased plant populations.

In the 1930s and 1940s, plantings of 4,000 to 8,000 plants per acre were standard practice. Today, planters can adapt to variable rates on the move and commonly place over 40,000 plants per acre.

So is there an optimum planting population? Are higher plant populations efficient and effective to gain yield and appropriately utilize the land base we have today?

Optimal plant population across all hybrids is related to several factors, including ear type, stress tolerance, timing and the severity of stress in relation to the crop’s development cycle.

In general, hybrids respond to higher populations by reducing the size of the ear on each plant. A hybrid that responds to reducing plant populations by increasing ear size is often referred to as a “flex-ear” hybrid, whereas a hybrid that has the “fixed-ear” characteristic produces the same-sized ear regardless of plant population.

Flex-ear hybrids tend to produce longer ears or larger diameter ears when planted at reduced populations. “Semi-flex” is the designation given to hybrids that fall somewhere in between flex and fixed ears.

As plant genetics shifted from 8,000 to 40,000 plants per acre, the corn plant itself endured radical changes. Hybrids that performed best at low populations were hybrids that expressed themselves in improved length, girth and also tended to be robust plants with sturdy stalks and big open leaves.

These hybrids usually photosynthesize sunlight well, promoting dynamic root development and making them reasonably drought tolerant. As breeders began to place more seeds per acre, row width narrowed and the genetics changed, giving birth to semi-flex corn hybrids.

These hybrids were bred with a reduced root mass, allowing for thicker planting populations. Eventually more and more varieties were developed to allow plant populations to reach new yield levels. Fixed-ear plants were bred to have more erect leaf structures, reduced root mass and decreased stalk sizes, and they eventually became the new norm.

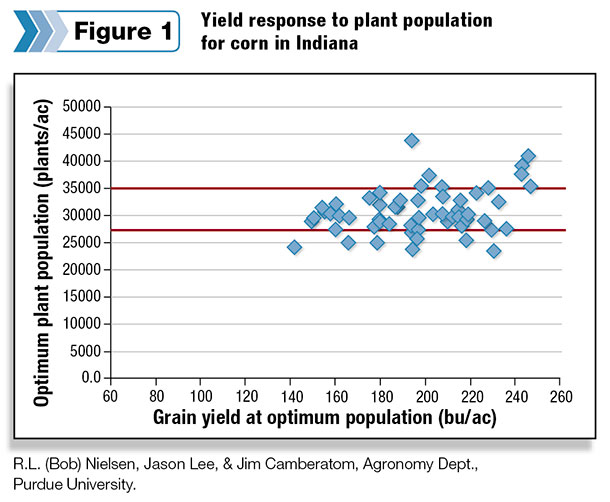

This progression has made sense and has been easily justified by continual increases in yields. As you see from the results of the study in Figure 1, yield increase has followed increased populations.

What we lacked in boldness of stature and structure we made up for with GMO technology to assist the plant to be its best. While studies show we can certainly outpace yield with overcrowding, we have sufficient evidence that certain fixed-ear or determinate corn hybrids can return higher yields.

Throughout this process of breeding for more yield, little attention has been paid to livestock feed quality, particularly corn grown for whole-plant silage. As plant breeders chased higher populations, thicker, denser-cored stalks gave way to smaller, woodier stalks.

The reasoning behind this is that the fibrous portions of the narrower stalks had to be more substantial to remain intact through harvest, and so quite logically they became harder. This resulted in a stalk that is less digestible for livestock whole-plant silage consumption. Crowding plants per acre consequently reduced plant sugars and decreased nutrient values of the stover and grain.

Drought tolerance also decreased as each plant has more competition for water and was bred to have a smaller root package in order to fit more plants per acre. Wide, dense core stalks require less bonding material to stand and move more nutrients into the plant to be passed on to the livestock consuming it.

These plants photosynthesize more sunlight and favor grain digestibility. Another consideration for a whole-plant silage producer would be to reduce plant populations of full-flex corn, increasing the overall starch percentage of the dry matter in the silage, resulting in increased available energy and decreased supplement grain costs.

We have to make sure that planting more seed is beneficial to an operation, because it comes at a cost. When comparing the average national grain yield from the last five years with the average national grain yield 20 years ago, we will see that the average yield is up 10 to 15 bushels per acre, but we planted a lot fewer seeds per acre 20 years ago.

Assuming that an 80,000 unit of corn costs you $300, the difference in yield when planted at a population of 40,000 versus 28,000 would have to be 15 additional bushels per acre.

Ultimately, we are at a crossroads when it comes to flex- versus fixed-ear corn hybrids, as both have their benefits when properly placed. On one hand, we have fixed-ear hybrids with narrower stalks, erect leaves and smaller root packages, which are ideal for planting at denser populations. These plants allow us to maximize our total grain production per acre.

We also have flex-ear hybrids, which allow you to spread a bag of seed further, have denser, more digestible stalks and with fewer “neighbors” can even add extra rows of kernels or grow longer.

Flex ears also come with a larger root package, offering some extra drought tolerance. As you can see, both fixed- and flex-ear hybrids have their place. To select which is right for us, we need to consider the destination of the corn to maximize the effectiveness of the crop produced. FG

-

Mark Kirk

- Nutritional Research Manager

- Masters Choice Inc.

- Email Mark Kirk