Under poor feeding management, the onset of these disorders is almost assured. The objective of feeding management is to provide a ration with balanced nutrition in a manner that maximizes nutrient utilization while lessening the occurrence of digestive disorders.

Anatomical peculiarities of the equine digestive tract

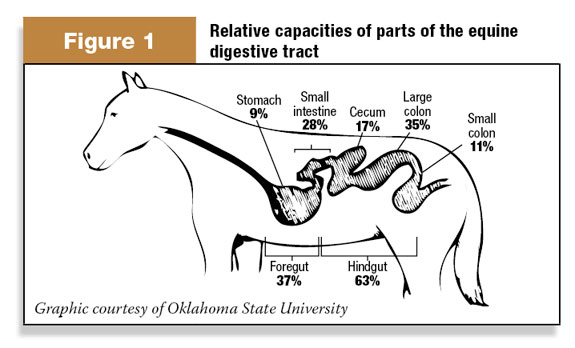

The horse’s digestive tract can be divided into two functional divisions: foregut and hindgut. The foregut of the horse is made up of the mouth, esophagus, stomach and small intestine.

It functions similarly to the digestive tract of the pig in that it is made of a simple, one-compartment stomach, followed by the small intestine.

The hindgut of the horse is comprised of the cecum, large colon, small colon and rectum. The cecum functions much like the rumen of a cow in that it is a relatively large, fermentative vat housing microbes that aid digestion.

These microbes break down nutrient sources that would otherwise be unavailable to the horse. Each part of the digestive tract has peculiarities that relate to feeding management.

Mouth

The mouth is responsible for the initial breakdown and swallowing of feedstuffs. Chewing reduces the size of large-particle feedstuffs and breaks up the less digestible, outer coverings of grains and forages.

Additionally, mastication stimulates salivary glands to release saliva, which assists in lubrication of feed for swallowing.

Since proper denture conformation is necessary for mastication, inspection of the horse’s teeth by a qualified individual should be a routine management procedure.

As horses age, dental conformation can be expected to deteriorate. Consequently, older horses require more frequent inspection and treatment of teeth.

Signs of poor dental conformation include excessive loss of feed while eating, positioning the jaw or head sideways while chewing and evidence of general loss of condition and thriftiness.

Esophagus

The diameter and tone of the musculature of the esophagus make it difficult for the horse to expel gas through belching or vomiting. These are predisposing features to gastric rupture, gastric distention and colic.

Stomach

Compared to most livestock, the size of the horse’s stomach is small, about 10 percent of the volume of the total digestive tract.

The small size makes the rate of flow of feed material in the digestive tract through the stomach relatively fast.

Gastric emptying is dependent upon volume, so large meals can be expected to pass more quickly than feed eaten continuously at low volumes.

Studies have shown the majority of feed material in the digestive tract passes to the small intestine within 12 hours following a meal.

Small intestine

The small intestine is the main site of digestion and absorption of protein, energy, vitamins and minerals. Similar to the stomach, intake level of the feed influences rate of flow of ingested matter through the small intestine.

Large amounts fed in meal feedings increase rate of flow to the large intestine.

Cecum and colon

Ingested matter not previously digested or absorbed in the small intestine flows to the cecum and colon, which make up about 50 percent of the volume of the digestive tract.

The cecum and colon house bacterial, protozoal and fungal populations, which function in microbial digestion of feed material in the digestive tract. Many different products of microbial digestion are absorbed by the horse.

Passage of ingested matter through the large and small colon is relatively slow. Rates of flow through the colon may take up to several days following the time feed was eaten.

The diameter of different segments of the large colon varies abruptly. Additionally, the arrangement includes several flexures where the colon turns back onto itself.

Anatomical arrangements such as these predispose the horse to digestive

upset when nutrient flow is abnormal. ![]()

—Excerpts from extension.org

Graphic courtesy of Oklahoma State University

David W. Freeman

Extension Equine Specialist

Oklahoma State University

david.freeman@okstate.edu