Editor’s note: This is the second in a two-part series. In Part I (click here to read), we discussed dystocia in cattle and the importance of determining presentation, position and posture of the fetus when attempting to provide assistance.

In Part II, we review guidelines for determining when it is appropriate to apply traction to assist with delivery and discuss obstetrical techniques designed to minimize injury during the fetal extraction process.

And finally, we’ll review the consequences for cows and calves of ignoring these important obstetrical principles.

Delivery by forced extraction

Calving assistance errors are an important cause of dystocia-related injury resulting lameness in calves and cows, but by understanding the pelvic anatomy of both the cow and calf and what constitutes reasonable limits on extraction forces, many of these problems can be prevented.

For starters, whenever faced with a dystocia problem, the first step in evaluation is to determine presentation, position and posture. Assuming these are normal, determine if the calf can be delivered vaginally; in other words, is the pelvis of the cow large enough to permit delivery of the calf?

For a calf in anterior presentation, delivery is possible when the pasterns are extended at least a hand’s-width beyond the vulva. When the pasterns are extended beyond the vulva by this distance, it means that the widest part of the fetus’ pelvis is beyond the cow’s pelvis.

When the calf is presented in a posterior presentation, delivery is possible when the hocks are at or slightly beyond the vulva, which indicates that the shoulders of the calf are beyond the pelvis of the cow.

Forced extraction of a fetus should not be attempted until the above criteria have been met, as failure to do so will likely result in needless injury to either the cow and calf or both.

If these guidelines are met, one may begin the fetal extraction process by applying the following techniques:

1. Apply obstetrical chains or ropes to the fetus’ legs for assisted delivery and always use a half-hitch (above and below the fetlock) to avoid excessive pressure that might result in fracture of one or both legs.

2. When applying traction, always avoid excessive traction on the fetus. (No more than two persons should apply force at one time.)

3. Work with the cow and synchronize traction with pushing by the cow, and allow the cow to rest between each effort as needed.

4. When applying traction to the fetus, always pull straight backwards until the hips of the fetus have cleared the hips of the cow (or when the shoulders have cleared the hips of the cow in a fetus coming backwards); a downward pull prior to this point may complicate delivery.

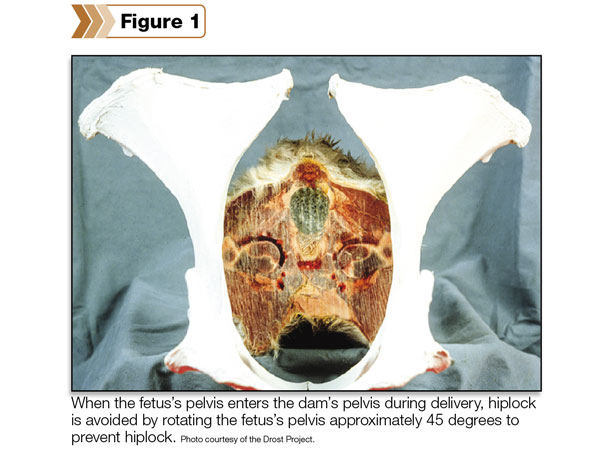

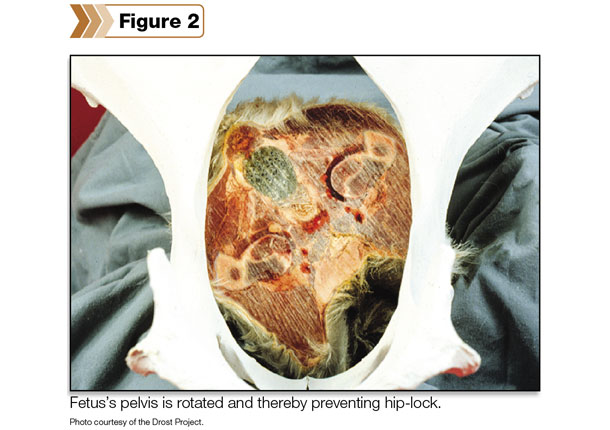

5. Always rotate the fetus during delivery approximately 45 degrees to take advantage of moving the widest part of the fetus’ hips through the widest part of the cow’s pelvis to avoid hip lock.

6. For fetuses that may be suffering from hypoxia (lack of oxygen) from prolonged calving, assistance to acquire colostrum may be necessary.

Specific injuries resulting in lameness are relatively rare in cattle with exception of those situations where a person or persons have applied excessive force during the delivery process.

In calves, fractures of the lower leg immediately above the fetlock are not uncommon when there has been excessive traction applied to the legs during delivery.

Femoral nerve paralysis is also a possible sequel to forced extraction resulting from severe stretching of the quadriceps muscle group that leads to vascular (blood vessel) and nerve damage.

Calves affected with femoral nerve paralysis will exhibit atrophy and decreased muscle tone of the quadriceps muscles and have difficulty advancing the affected limb or limbs. Fractures and dislocations of the hip and shoulder are also possible but normally occur less frequently.

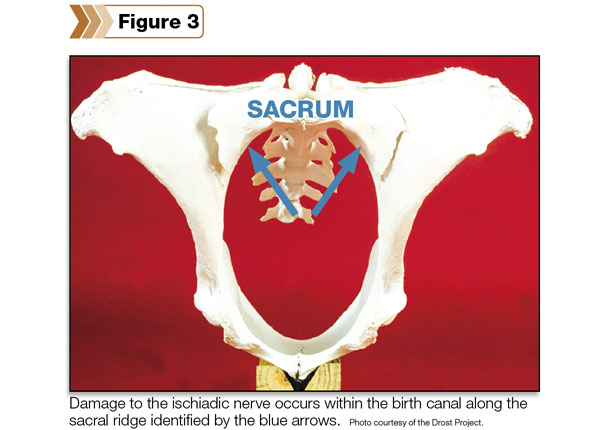

In cows, damage to the ischiadic (sciatic) and obturator nerves occurs subsequent to dystocia and protracted calving conditions. The actual lesion occurring in the ischiadic nerve (which is also spinal nerve – Lumbar 6) is believed to be within the birth canal on the sacral ridge and its site of exodus near the ischiadic notch in the wing of the ilium.

The obturator nerve also courses through the birth canal and is therefore vulnerable in cases of prolonged calving and dystocia.

Damage to the obturator and associated sciatic nerves often leads to a paresis or weakness of the adductor muscles located on the inner thighs of the rear legs. These muscles are designed to adduct the rear legs (that is, prevent the rear legs from splaying laterally).

Lateral splaying of the rear legs not only reduces stability but also increases the probability of subluxation of one or both hips, which in most cases leads to permanent disability or the down cow state.

The most common cause of the non-ambulatory state in beef cattle is calving paralysis, but it’s the secondary problems that often make this a permanent condition.

If the cow is unobserved and down for a prolonged period of time (for as little as six to 12 hours), she may be predisposed to a disorder known as “compartment syndrome.”

The sheer mass and weight of the cow’s body causes pressure necrosis (tissue death) and poor circulation of blood within the heavy muscles of the rear legs. The result is permanent damage to muscles that frequently leads to an irreversible down cow state.

Finally, although damage to the ischiadic nerve usually occurs within the birth canal along the sacral ridge, clinical symptoms are often manifested in the lower limbs as damage to the distal branches of the peroneal and tibial nerves.

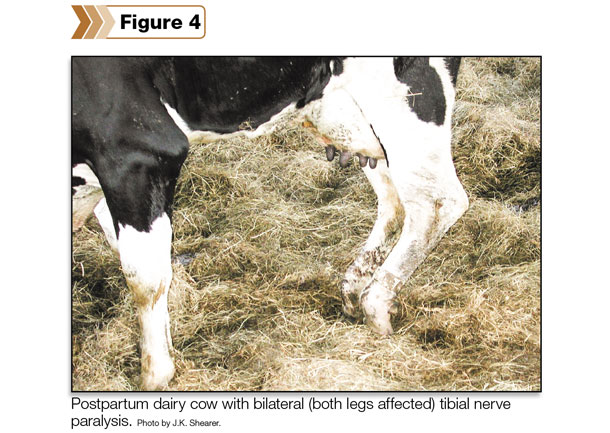

In cases of damage to the peroneal nerve, cows will tend to knuckle over onto the dorsum of the pastern. When the tibial nerve is affected, the hock joint will appear lowered and the fetlock joint will be flexed.

In summary, the approach to managing dystocia in cattle has significant impact on postpartum health and well-being of cows and calves. We can prevent dystocia-related lameness in both by careful attention to the basics of bovine obstetrics:

-

Never try to extract a fetus without first assuring that the presentation, position and posture of the calf are correct.

- Do not apply traction to the calf before determining if the calf can be delivered by forced extraction.

- Work with the cow and pull straight backward while rotating the fetus approximately 45 degrees to avoid hip lock.

Application of these techniques will not only make delivery of calves easier, but it will also help to prevent potential for postpartum injury and lameness in cows and calves.