Dr. Robert Mortimer from Colorado State University has written “Calving and Calving Difficulties,” and Dr. Richard Randle from the University of Nebraska has written “Assisting the Beef Cow at Calving Time.” Both resources provide information for assisting a difficult birth and are the basis for the guidelines given here.

In a normal delivery, the calf should be born within two to three hours after the water sac appears in heifers and one to two hours in cows. If it is longer than this, the calf may be born dead or weak.

Timing is critical to providing help, so checking on calving heifers or cows frequently is important. Good facilities, equipment and tools can provide the restraint and assistance needed to safely deliver a live, healthy calf.

Visit with your veterinarian for advice on when to call him. The goal of assisting a difficult birth is to minimize stress to both the cow and calf. Experience will aid in determining if the calf can be delivered with assistance or if a caesarean is needed.

This can often be decided when examining the cow for the first time. The following are steps to use to decide if a calf can be delivered or if a caesarean should be done.

Steps in calving assistance

Examine the pelvis vaginally to determine how much the cervix is dilated. The cow’s vulva and rectum should be scrubbed and clean prior to entry. A plastic shoulder-length OB sleeve should be worn and lubrication used when examining the cow.

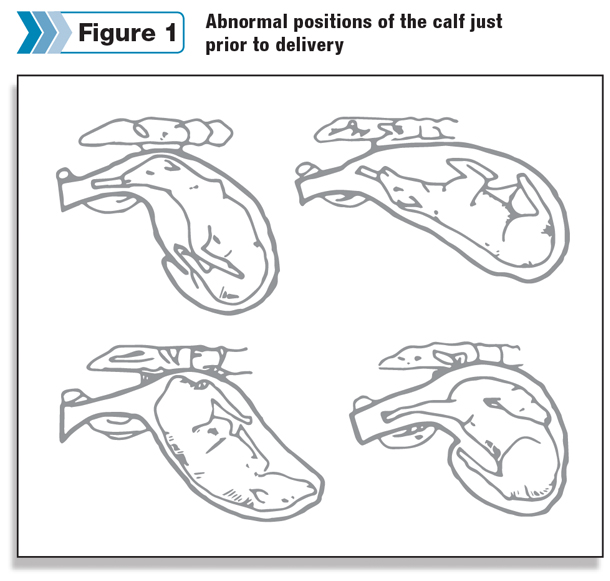

Determine if the calf is alive and evaluate the situation based on what Dr. Mortimer identifies as the 3 P’s of presentation, position and posture of the calf. Presentation refers to whether the calf is coming frontward, backward or transverse.

Position refers to whether the calf is right-side-up or upside-down. Posture refers to the relationship of the calf’s legs and head to its own body.

The size of the calf in comparison to the birth canal should also be determined when examining the situation. A big calf pulled through a small pelvis may kill the calf and injure/paralyze the cow. If it is determined the calf is too big while the head and front feet are still in the birth canal, there is still the chance for a successful caesarean.

Dr. Mortimer recommends calling for professional help when a producer encounters any of the following during examination or early on in the delivery process:

- A problem they don’t know how to deal with.

- A problem they understand and know the solution to but are unable to handle.

- A problem they understand, but after 30 minutes of work they aren’t making progress toward the solution.

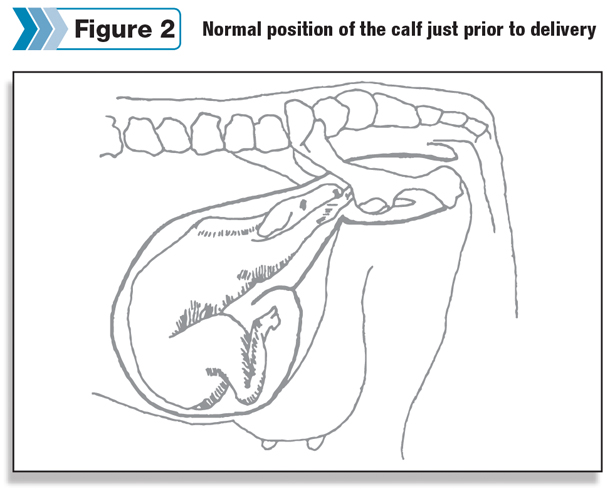

The rest of this article will describe assisting a normal presentation where the calf is positioned right-side-up with the front legs postured so that they can move into the birth canal (Figure 2).

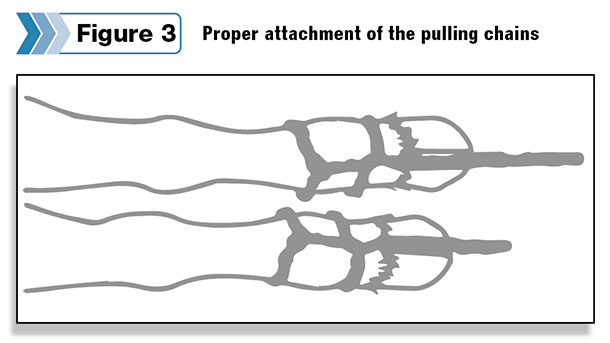

Attach the chains or nylon straps to the front legs of the calf, placing the loop of each chain around each leg. Then slide the chains up on the cannon bone 2 to 3 inches above the fetlocks (ankle joints) and dew claws.

Place a second loop between the fetlocks and the top of the hoof. Make sure the chain pulls from either the top of the leg over the fetlocks (Figure 3) or the bottom of the leg (dew claw side).

Once the chains are in place, if the cow isn’t already lying down, lay the cow down on her right side. This allows the calf to enter relatively straight into the pelvis. Attach the obstetrical handles to the chains and gently pull, making sure the chains haven’t slipped.

Pulling should only be applied when the cow is pushing with abdominal pressure. Start pulling on the calf’s left leg, which is the down leg if the cow is lying on her right side.

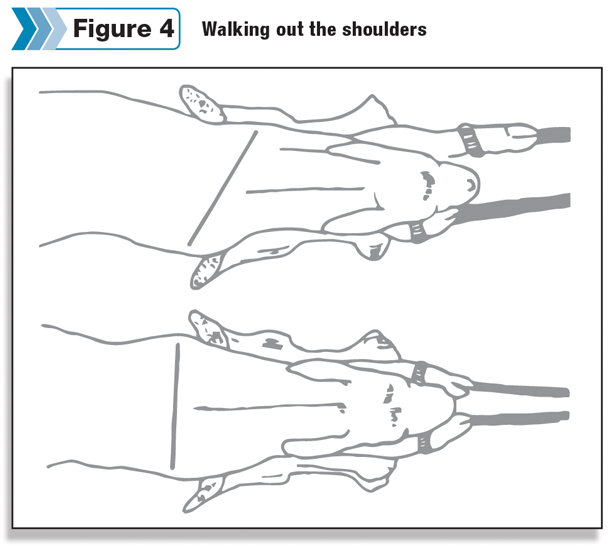

This leg usually comes through the pelvis easily. The real test for delivery is if the second shoulder can be moved past the cow’s pelvis. Once the first shoulder is through the pelvis, it should be held in place and traction applied to the other leg.

This process is called “walking out the shoulders.” Good judgment should be applied in the use of pressure on the calf. If the calf’s other shoulder will not move through the pelvis at this point with appropriate tension, a cesarean is recommended.

The amount of tension should be limited to the strength of one man per leg. Two strong men can exert from 400 to 600 pounds of force, while the inappropriate use of a calf puller could exceed 2,000 pounds of force.

Excessive pressure may deliver the calf but will increase the chance of death to the calf during delivery and trauma to the cow. A calf puller should be used correctly and only by experienced people. A calf puller can apply traction equivalent to the pull of seven men.

Once the shoulders have been moved through the pelvis (Figure 4), the calf should be able to be delivered using “bilateral traction,” where each leg is pulled together. Before the pelvis of the calf enters the cow’s pelvis, a break can be taken. This is what usually occurs in a normal delivery.

At this time the umbilical cord is compressed, and the calf should begin breathing on its own. This is also the time when an oversized calf is rotated a quarter-turn so the widest part of the calf’s pelvis is going through the widest diameter of the cow’s pelvis.

Once the calf has reached this point, constant pulling will not allow the calf to expand its chest and breathe. Make sure the calf is breathing and observe that the calf continues to breathe as the calf’s hips are pulled through the pelvis of the cow.

The “Calving and Calving Difficulties” publication written by Dr. Mortimer gives excellent instruction in how to correct abnormal presentations.

Stockmen calving cows would do well to review the advice given by Dr. Mortimer and think through how the techniques described could benefit them this calving season.

Good planning, preparation and the application of proper techniques can improve calf survival when difficult deliveries occur due to calf size or abnormal situations. ![]()

-

Aaron Berger

- University of Nebraska

- South Panhandle Extension Unit

- Email Aaron Berger