Multispecies grazing could be a great strategy to improve pasture quality and increase economic returns.

Some pastures may be better suited to grazing one livestock species; however, pastures with high plant diversity and variations in topography, such as Western rangelands or a pasture that has been encroached with weeds and brush, are ideal for multispecies grazing. Through multispecies grazing, there are several opportunities to better utilize and improve returns on resources:

1. Maintain or improve forage production and diversity

2. Increase animal units and grazing distribution

3. Raise and market multiple products from a common pasture

4. Manage invasive weeds, invasive annual grasses and brush encroachment

5. Manage animal parasite loads

6. Decrease predator threats

Maximizing forage resources

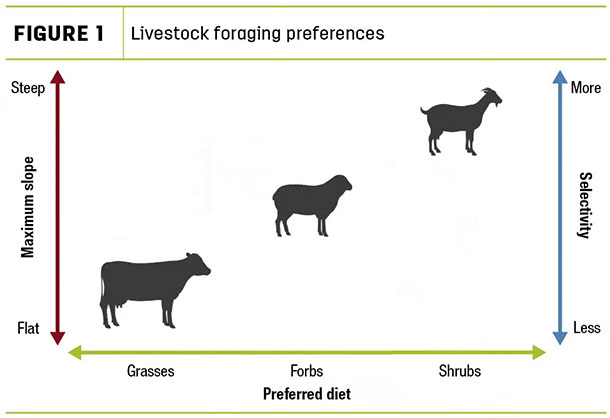

While the dietary preferences of cattle, sheep and goats overlap, they differ enough they can complement one another in a pasture diverse in plant species. Although grazing livestock will each feed on grasses, forbs and shrubs at some point, cattle forage predominantly on grasses, sheep primarily select forbs, and goats readily browse on shrubs.

Grazing two or all three species in combination in a pasture produces a more uniform utilization of the available vegetation and can result in increased stocking rates. For example, sheep and cattle have approximately 35 percent dietary overlap, which decreases when plant availability and plant diversity increase.

Grazing two or all three species in combination in a pasture produces a more uniform utilization of the available vegetation and can result in increased stocking rates. For example, sheep and cattle have approximately 35 percent dietary overlap, which decreases when plant availability and plant diversity increase.

Cattle typically do not change their dietary preferences when other grazing animals are present; however, sheep and goats will alter their dietary choices toward more obtainable vegetation (i.e., forbs or shrubs cattle avoid) when grazed alongside cattle. This complementary behavior can lead to a 15 to 20 percent increase in carrying capacity when cattle graze with sheep or goats.

Additionally, preferred topography differs by livestock species. Cattle prefer to graze areas made up of less than 20 percent slope and rarely traverse slopes of 20 to 40 percent grade. Cattle are not selective grazers, and they take in large quantities of feed; therefore, they need more water than sheep and goats.

Because of their physiology, cattle tend to spend more time in low, flat areas with easy access to water, such as riparian areas, and typically will not travel more than 1.5 miles from water to graze. Sheep readily traverse slopes up to 45 percent grade and typically stay in dry, upland areas as opposed to wet-bottom lands, such as riparian areas. Goats are opportunistic grazers and are extremely agile.

They have a unique ability to reach and climb for feed. Sheep and goats are also willing to travel much farther from water than cattle.

Differences in grazing preferences makes multispecies grazing especially effective in rangeland settings and pastures where there is variation in plant species and topography. Because cattle prefer to stay lower and near water, and sheep and goats tend to traverse steeper terrain, grazing them in common allows for optimal pasture utilization each year.

Differences in grazing preferences makes multispecies grazing especially effective in rangeland settings and pastures where there is variation in plant species and topography. Because cattle prefer to stay lower and near water, and sheep and goats tend to traverse steeper terrain, grazing them in common allows for optimal pasture utilization each year.

Furthermore, under circumstances where pastures need to be rested, grazing cattle one year and sheep the next year would allow a year of rest for either the riparian areas or uplands because of their preferred grazing behaviors.

The addition of an additional livestock species in a pasture also allows producers to raise and market multiple commodities using the same piece of land. Dual-livestock operations may have added stability compared to single-species operations because they have access to additional marketing opportunities and can rely on one livestock species to balance the other during bad market years.

Furthermore, because the carrying capacity can increase 15 to 20 percent with the addition of a second species, the return on income may also be improved by 15 to 20 percent.

Targeted grazing

One of the most frustrating things as a cattle producer is fighting the spread of invasive weeds and annual grasses, and keeping perennial grasses healthy and productive. Often, cattle will not consume those invasive plants, leading to a wearisome cycle of spraying weeds and having them return or pop up somewhere else.

Sheep and goats can be an effective tool in removing and inhibiting invasive plants because of their willingness to consume them, which can help improve the overall health of a pasture. With invasive weeds like leafy spurge, whitetop, spotted knapweed and thistles, sheep and goats can be used to graze ahead of cattle and remove the tops as they are flowering, prior to seed production, to help prevent them from spreading.

Invasive annual grasses, such as cheatgrass and medusahead, should be grazed while green and prior to seed production. Because sheep and goats graze more selectively than cattle, they tend to be more effective at managing invasive annual grasses. However, cattle can also be used. These grasses tend to be most palatable at the time of optimal removal for effective management.

Larkspur is a poisonous weed toxic to cattle, but sheep can tolerate up to four times more larkspur than cattle. This tolerance makes them ideal for grazing ahead of cattle to help reduce the likelihood of overconsumption by cattle.

In addition to weed management, goats are uniquely adept at managing overgrown brush and shrubs. Grazing goats at a high stocking rate may be the best way to decrease the canopy of unwanted shrubs. Because of their willingness to climb and traverse rough terrain, goats are a great option to decrease vegetation overgrowth in pasture areas nontraversable by cattle or sheep.

Grazing to reduce fire fuel loads is also most effective with multispecies grazing. To decrease the overall fire fuel load, cattle can be used to reduce the biomass of grasses, and sheep and goats can be used to target weeds and shrubs.

Control parasites and predators

Parasites are typically specific to cattle, sheep and goats and are most often ingested through grazing. Multispecies grazing can be used to decrease parasite load in livestock. Alternating grazing between species in a pasture allows the sheep- or goat-specific parasite larvae to be ingested by cattle through consumption of the blades of grass on which they reside and, alternately, the consumption of cattle-specific parasite larvae to be ingested by sheep and goats.

Additionally, as cattle or sheep and goats come off a pasture, they should not return for 40 to 80 days to most effectively decrease the infectiousness of the parasites, especially in wet pastures. A recommended rotational strategy would be to graze cattle first, allow the pasture an approximate 30-day regrowth period followed by sheep or goat grazing and then graze cattle again after another 30-day regrowth period.

Predators such as wolves, coyotes and stray dogs can be a major problem in some areas of the country. When cattle and sheep are trained to graze together, cattle provide a buffer for sheep from predators. Cattle, on the other hand, may benefit as much as the sheep from the sheepdogs trained to live with and protect the livestock.

Considerations for multispecies grazing

While there are many benefits to grazing multiple species of livestock in common, there are also several considerations to make when transitioning into such an endeavor. First, the overhead of installing fences and handling facilities to accommodate the new livestock may outweigh the benefits.

Second, there is a chance that, by adding a new livestock species, the original livestock species numbers may need to be reduced. Depending on the operation and individual circumstances, this may not be a negative thing from the economic standpoint, but it is something to consider.

Third, two or more species of livestock may impose labor and scheduling conflicts, so careful planning is needed before deciding.

Adding a species to the operation would require diligent homework to learn all the required nutrition, breeding practices, marketing, health, etc., for that species.

Multispecies grazing can have many benefits for the overall health of the pastures and for the financial bottom line. The future of the livestock industry, especially in the West, relies heavily on finding the land and forage resources to support livestock production. Multispecies grazing provides an opportunity to get more livestock production out of less land and gives us tools to keep that land healthy. ![]()

PHOTO 1: Cattle prefer grazing areas with less slope. Photo by Cassidy Woolsey.

PHOTO 2: Sheep do not require as much water as cattle. Photo by Carrie Veselka.

PHOTO 3: Goats are able to travel farther than cattle. Photo Lynn Jaynes.

Melinda Ellison is a range livestock extension specialist in the Nancy M. Cummings research, extension and education center in the animal and veterinary science department at the University of Idaho.