Managing for reproductive success actually begins prior to calving. Effective planning for reproductive health and limiting the impact of anestrus will ensure producers are setting their cows up for the breeding season.

Cows cycling early in the breeding season have a greater chance of higher pregnancy rates and therefore increase their opportunity to become pregnant during a limited breeding season. Breeding season length will influence the uniformity of calves – subsequently, calves born early in the calving season will weigh more at weaning. Additionally, replacement heifers born early in the calving season are more likely to conceive early in the breeding season as yearlings and stay longer in the herd.

However, one of the primary reasons for culling cows on a beef cattle operation is the failure to rebreed. To have a successful breeding season, it is vital for that cow to cycle and conceive early in the breeding season. Therefore, understanding how to manage the postpartum interval (PPI), how body condition can impact PPI and rebreeding, and how we can use reproductive technologies to manage anestrus will be important when setting cattle up for a successful breeding season.

Managing the postpartum interval

To maintain a yearly calving interval, beef cows must recover from the nutrient and physical demands of calving and lactation, and will have 80 to 85 days to return to estrus after calving to potentially maintain a yearly calving interval. Failure to successfully manage the PPI is one of the major causes of reproductive loss, especially so in young cows.

After calving, cows go through postpartum anestrus, a period in which cows do not experience estrous cycles. This period can vary in length due to factors such as uterine involution, short estrous cycles, nutritional status and suckling effect.

Uterine involution can be defined as the structural and functional regression of the uterus to a status that can support another pregnancy. This includes returning to a non-pregnant size, shape and position, shedding of all fetal membranes and repair of the uterine tissues. This process is completed in approximately 20 to 40 days following calving if no complications arise. However, factors such as nutrient restriction, calving difficulty and disease will delay normal involution.

During the first ovulation postpartum, why is the first estrous cycle short? The corpus luteum during a short estrus secretes less progesterone, is smaller and is less responsive to stimulation. Therefore, fertility is decreased and the majority of cows will experience a short estrous cycle (an estrous cycle of 10 days or less). When a short estrous cycle occurs, the corpus luteum will regress and the cow will return to heat before maternal recognition of pregnancy occurs. That means that cows need to initiate estrous cycles prior to the start of the breeding season to become pregnant. If cows do not exhibit estrus or are still in anestrus, the chances for those females to cycle or get bred early in the breeding season decreases.

Body condition and nutritional status prior to calving are influential in postpartum reproductive performance. Therefore, managing nutrient intake and body condition score (BCS) before and after calving contributes to improved reproductive efficiency within a herd. For reproductive success, BCS (on a 9-point scale) should target a 5 to 5.5 for mature females and 5.5 to 6 for first-calf heifers by the breeding season.

The act of suckling and presence of a calf has the greatest effect on PPI length. Temporarily removing calves from cows for 48 hours or weaning calves has been shown to trigger anestrous cows in a body condition of 4 or 5 to start cycling.

BCS influences postpartum interval

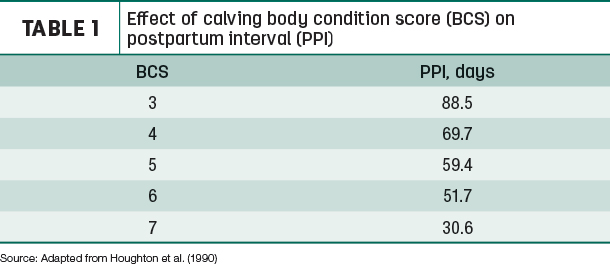

BCS is an effective management tool to estimate the energy reserves of a cow. Research has shown that body condition at the time of calving has the greatest impact on subsequent rebreeding performance (Table 1).

As illustrated in Table 1, as BCS decreases in females at calving, resumption of estrus or PPI increases.

Furthermore, several studies indicate that cows which gain a BCS during the last trimester tend to have shorter PPI compared to those that maintain condition. Therefore, nutritional adjustments in the last trimester prior to calving to increase calving BCS could impact reproductive performance and should be part of a nutritional management strategy.

How to move up late-calving cows in the breeding season?

Utilizing a controlled intravaginal drug release (CIDR), which is a slow-release progesterone device, is a common estrous synchronization tool that can be used to “jump-start” the cycle of late-calving cows or manipulate the cycle in cows and heifers. Research has shown that inserting the CIDR no sooner than 20 days post-calving can initiate cycling earlier than may occur naturally. Even if artificial insemination (A.I.) is not being utilized, estrous synchronization can help decrease the PPI of thin BCS cows in the breeding season.

One resource that allows producers to compare costs of protocols and generate calendars specific to timing of synchronization drugs, CIDR insertion and removal, and when to artificially inseminate is the Estrus Synchronization Planner.

Overall, evaluating body condition prior to calving and through the breeding season will allow producers to make appropriate nutritional changes to ensure those females are in adequate condition for the next breeding season. Optimal reproductive performance of your cow herd requires that cows target a BCS of 5 or better. For early postpartum cows, utilizing estrous synchronization tools that include a progestin may be advantageous.

References omitted but are available upon request by sending an email to the editor.