Compared to the decline seen in the beef industry during the 1980s and 1990s, red meat has been taken off the health hit list, and lean red meat is now in the good graces of our local family practitioner.

Low-carb diets are seeing new-found fame among people trying to reduce their waist lines and, overall, consumers want protein in their diet. The USDA forecasted that in 2018, the average person consumed almost 10 ounces of meat and poultry per day (almost double the recommended daily level of protein). Global meat consumption is also projected to increase more than 4% over the next 10 years. As countries develop and incomes rise, so do the options to consume higher-priced protein sources such as beef.

This provides the U.S. with a difficult question: How do we produce more beef, on less land, while improving efficiencies and production in a sustainable manner? In 2012, the meat industry processed 33.2 million cattle, which equated to 25.8 billion pounds of beef. The goal moving forward will be to figure out how to continue to increase pounds of beef without drastically increasing our cattle on feed number.

The easiest way for us as an industry to achieve this goal is to find ways to improve cattle health management, enhance feed efficiencies and increase our carcass yields (without reducing quality grade). Achievable, but complicated. One aspect that may play a role in overall health and efficiencies of feedlot animals and cause impacts to carcass yields are liver abscesses.

Reducing condemnation

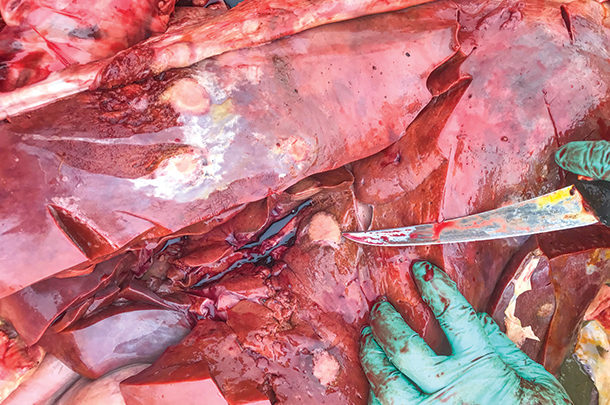

Liver abscesses are the primary cause of liver condemnation in feedlot cattle harvested in the U.S. According to the 2016 National Beef Quality Audit report, 30.8% of livers were condemned at harvest. In 2011, only 20.9% of livers were condemned.

This is particularly concerning since we have more research and technologies in the feedyard than we have ever had in the past, nutritional management approaches, such as changing ration compositions leading to lower-starch rations, better understanding of the causes and bacteria associated with liver abscesses and potential feed additives to show control of liver abscesses – and yet, rates in cattle continue to increase every year.

Liver abscesses cost the U.S. cattle industry an estimated $60 million per year. Currently, it isn’t the reduction in sellable livers that are a major component of economic loss (livers are worth about $3); it is the cost of the adhered livers in terms of the labor and time it takes to trim the carcass.

However, liver abscesses in feedlot cattle are not only an economic issue for the beef packers. Liver abscesses are a telltale sign that the animal’s performance potential wasn’t 100%, which may lead to economic losses for producers.

Feeding high-energy diets is generally associated with liver abscesses. A direct mechanism and pathway for development has yet to be fully explained, but most researchers agree that ruminitis, damage to the ruminal wall, is the primary route. The primary bacteria associated with liver abscesses is Fusobacterium necrophorum, an anaerobic bacterium that originates in the rumen. However, researchers are finding that other bacteria are playing a role in the overall etiology of an abscess.

In a recent study conducted at Colorado State University, researchers found that 12 different bacteria were present in all collected liver abscess samples. Enterobacteriaceae bacteria such as Salmonella enterica have been present in abscesses in several recent trials. It is still unknown how salmonella gets to the liver and what role this may play. However, as our understanding of what bacteria are within liver abscesses expands, so will our understanding regarding how to manage the issue.

One direction of focus resulting from discovering bacteria such as salmonella are present within an abscess is the importance of gastrointestinal health related to liver abscesses. Factors such as leaky gut would allow these bacteria to break out of the intestine and into the portal system, causing these bacteria to gain entry to the liver via the intestine.

Tylosin has been the primary antibiotic control option for producers. Although tylosin is effective, consumer concerns regarding antibiotics and anti-microbial resistance have revitalized the industry to start searching for an alternative solution to controlling liver abscesses. Vaccines, probiotics, prebiotics, essential oils, nutritional management and feed ingredients are all being researched as potential solutions.

Management keys

However, most producers, veterinarians and nutritionists agree there isn’t a single silver bullet out there, and finding the right combination of products in the most cost-effective manner will be the optimal solution. Historically, the foundational objective for controlling liver abscesses is keeping the rumen healthy so that bacteria can’t break through the rumen wall. However, protecting the gastrointestinal tract may be just as critical for managing abscesses.

To ensure rumen and intestinal health within a feedlot animal, feed management is the top factor in the success of abscess prevention. Without a well-managed nutrition program, consistent feeding frequency and bunk management program, no additive in the world will show significant benefits in abscess control. In a review done in 2015, it was concluded that although roughage level provided during growing and finishing diets influences the incidence of liver abscesses, the type of roughage provided and roughage passage rate out of the rumen will significantly influence abscess development.

Although detecting a liver abscess in live cattle is virtually impossible, the effects of severe abscesses can be seen in factors that will directly contribute to a producer’s bottom line. Performance factors such as reduced average daily gain (ADG) and growth to feed may be greatly affected. During 12 experiments utilizing 566 head of individually fed cattle, researchers found that final weights for cattle with an A+ liver score (Elanco Liver Check Service; A+ = one or more large or multiple small, active abscesses at harvest) were significantly less.

Additionally, hot carcass weights (HCW) were lighter and dressing percentage was less for cattle with an A+ abscess. During this study, cattle with A+ liver scores gained 16.6% less than cattle with healthy livers and had reduced daily dry matter intake (DMI) during the finishing period. A more recent study found that severe pulmonary lesions were associated with decreased performance and 15.65 pounds less HCW than healthy cattle.

With the obvious economic issues facing the industry, one additive emerging as a potential novel method to control liver abscesses is the role of good bacteria. Research-based bacteria strains that have been shown to provide additional rumen wall and intestinal wall benefits may provide producers with one more reason to feed cattle a probiotic.

Recently, a field study was conducted at a commercial feedlot in the Texas Panhandle to evaluate the relative efficacy of feeding a probiotic (Lactobacillus animalis plus Propionibacterium freudenreichii 2.0x109 colony-forming units per head per day) versus a control group on feedlot performance, carcass characteristics, animal health and liver abscess scores in calf-fed Holsteins (n= 11,877). All calves were fed tylosin.

The probiotic cattle had a higher dressing percentage compared to control (61.44% versus 61.17%). Additionally, there were significantly greater edible livers in the probiotic group compared to control and a lower prevalence of A+ liver abscess scores and adhered livers in the probiotic group (42% versus 49.46%; 24.42% versus 32%). In addition to this trial, several trials have been done with these specific strains of bacteria in beef calves fed probiotics with tylosin and Holstein calves fed no tylosin. Consistently, the addition of this probiotic combination has shown to reduce liver abscess severity.

Liver abscesses are an economic liability to both producers and packers. Not only do they cost the meat industry money in terms of inedible product and trim loss, but they also reduce cattle feed efficiency. If liver abscesses are found at harvest, the animal was not performing at its optimum level, as either a breakdown in the rumen or gut epithelium allowed bacteria into the portal system. The liver abscess was the end result, but what could that animal have achieved in terms of yield if its immune system wasn’t combating a bacterial infection prior to harvest?

Probiotics may be a worthy alternative to current anti-microbials on the market, but more research needs to be done to determine the overall benefits to the animal as liver abscess severity is reduced. Although there isn’t one magical way to control abscesses, as an industry, we need to be driven to find optimal programs for reducing liver abscess and increasing the economic value of the animal.