Liver flukes, small, shale-covered pests found in the liver, are no longer a regional parasite problem. Previously an issue only producers in the wet regions of the Gulf and Pacific coasts had to deal with, these pests have become a worsening problem for producers across the country.

The life cycle

“The liver fluke is a very unique parasite,” says Jody Wade, DVM, Boehringer Ingelheim. “They have one of the most unique life cycles that I have ever been exposed to.”

The parasite is fairly small, about 1 inch by a half-inch, Wade says. They are covered in shale and have a spiny structure on their exoskeleton. As they migrate through the tissues, through the bile duct and the liver, they cause lots of damage because of this hard shell that they're covered in. And the damage is done long before you ever really know they are even there.

Unfortunately, you can’t look at an animal and see that they are infected by this parasite, Wade says.

“You have to do some sampling of fecal matter to determine if you have liver flukes,” says Mark Alley, DVM, Zoetis beef technical services.

While the animal’s productivity goes down, typically it isn’t until they get to slaughter and the liver is condemned that the parasite is detected. And that’s where it really costs us, Wade says.

“When we were first starting to look for liver flukes, industry experts thought we didn’t need to look at anything less than 9 months old,” Wade says. “Unfortunately, now we're finding them in animals less than 9 months old. So we know that these cattle are getting exposed really early in life.”

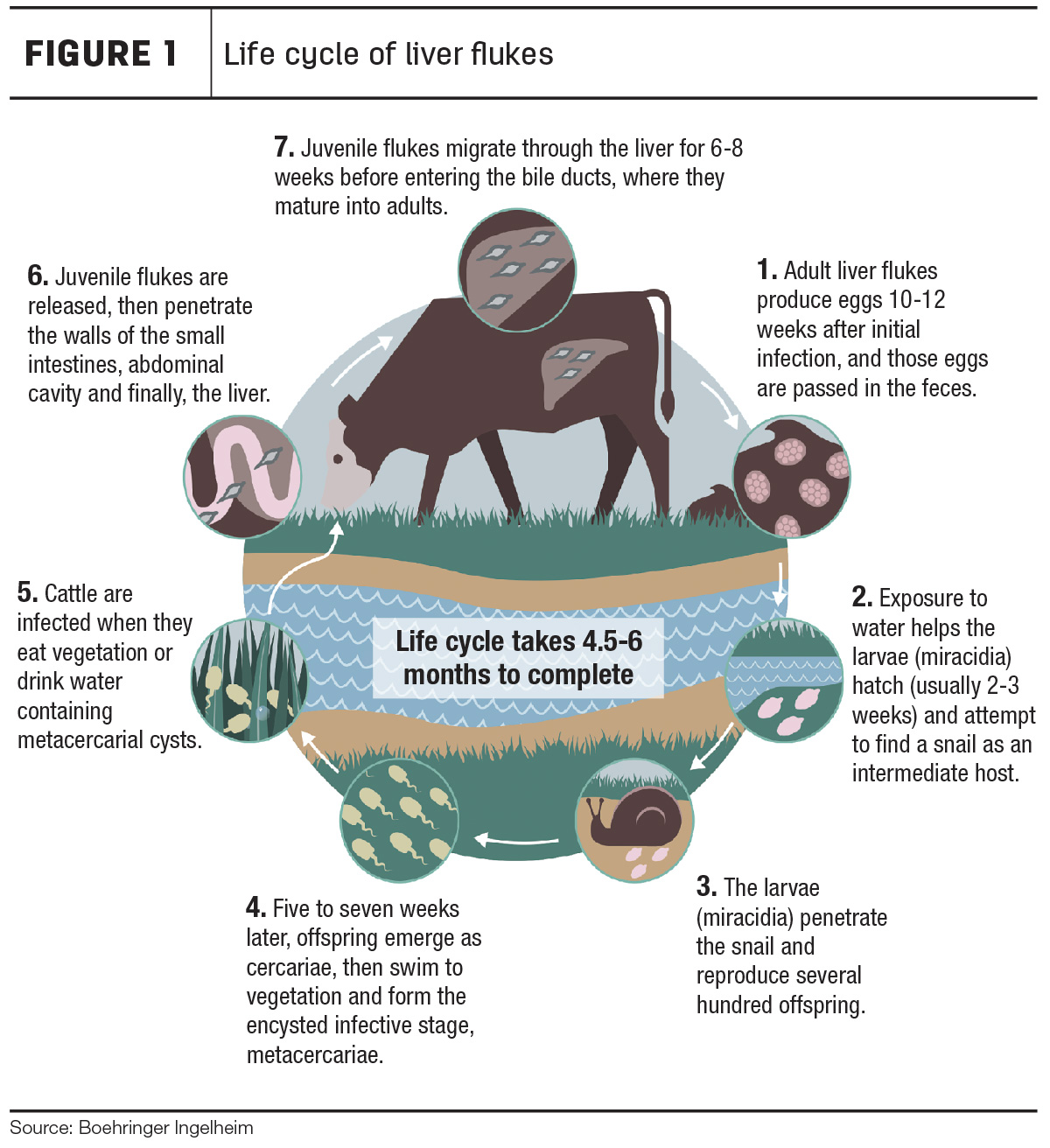

The life cycle of a liver fluke starts in the liver of an animal where adult flukes lay eggs, which are then laid out on pasture through the feces of the animal. While on pasture, they have to go through an intermediate host before they continue their life cycle.

“Once those eggs hit the ground, if it happens to be really dry outside, those eggs can remain viable for about a year,” Wade says. “They can just lay there on pasture, but once they get more mature, have standing water or things like that, then they'll start to hatch and, once they hatch, they'll start looking for that intermediate host."

Wade continues, “They can stay in the fecal matter for quite a long period of time. And they are very smart, so if the weather conditions are not right for them and the moisture is not there, then they can just hang out for as long as a year if conditions are not correct. And then once the conditions are good, then they do their thing. Additionally, the winters are not too hard on them and they can survive through those conditions. The perfect conditions for them are between 59 degrees and about 72 degrees Fahrenheit, but even below that they still develop. It's just a little slower process with slower metabolic rates, but they’ll still get there.”

The intermediate host is a common mud snail, Wade says. As the liver flukes hatch, the snail can either pick up the flukes by eating them or the flukes can swim to the snail and penetrate the tissue. The liver fluke stays in the snail for a few weeks before exiting and swimming through the water to the grasses that cattle eat. Cattle will then pick up the fluke by eating the grasses, and the fluke makes its way through the animal to the gallbladder, bile duct and liver.

“Clinically, we could see animals that actually die if they get a super infestation,” Alley says. “Oftentimes, it's more of a lack of production that we'll end up seeing, like weight loss of adult animals or in new grazing animals in the cow-calf sector. Then once you get to the feedlot sector, you'll see the damage done in the livers, and those animals probably were having some negative impacts on efficiency. But unfortunately, the damage has likely already been done at that point.”

At slaughter and processing, profit will be lost as infected livers cannot be used and will be thrown away.

Moving cross country

“If the environment is good for the snail, that means it's probably good for the liver fluke as well,” Alley says.

For Wade, who is located in northern Alabama and Tennessee, liver flukes weren’t something he had to think about in his practice in the past. However, that has changed. Hauled up from the coastal states when cattle are purchased from those areas, the liver flukes hitched a ride and are now being found across the country in all breeds of cattle, Wade says.

“What we are seeing is not a surprise when you start looking at the number of cattle we move,” Alley says. “We definitely see liver flukes in areas where we may not have historically seen them. If the cattle end up in an area where there's no snails, it really can be an end game for the flukes. But if the snail is there, then we can replicate and we can actually create the problem on that operation long term.”

Treatment and prevention

While there are a few products available to treat liver flukes, there isn’t anything that will kill them in the juvenile stages, Wade says.

“The earliest we can start killing them is usually eight to 12 weeks after those cattle have been infected,” Wade says. “So a lot of that damage is probably already done as the juveniles migrate through the tissue in the first eight to 12 weeks while they're reaching adulthood. Our products that we have available are really good for the adult stages, but we need something that's going to be better on the juvenile stages so we can cut it out a little quicker.”

One of the best things you can do when it comes to liver flukes is to prevent them through management practices. While treatment only kills the adults, it does eliminate the adult females that are going to lay eggs back out on pasture and contaminate more pasture, Wade says. Additionally, keeping cattle from grazing wet areas with standing water where there are snails, the host animal for liver flukes, will cut down on cattle getting infected with these parasites, Wade adds.

“At this point, from a prevention standpoint, all we have available to us is we can remove cattle from the habitat where the snail is,” Alley says. “That is one mechanism of control. They have tried different things to kill the snails, and it's just very difficult to treat the environment.”

The frequency of treatment will depend on the location of the operation. In swampy areas where snails thrive, there may need to be more than one treatment per year, Alley says. In other areas, one treatment yearly may be adequate.

“The main thing when we're looking at managing liver flukes is trying to manage that environment,” Alley says. “We need to try to reduce the total number of parasites that are going to be on the pasture for the next generation of cattle that are going to be there.”