As we approach midsummer, there are important reasons to consider deworming. Almost immediately after cattle are turned out on contaminated green grass, they begin picking up parasites that can start doing damage in a very short time. If cattle are dewormed at turnout and not again until they come off the pasture in the fall, they have several months to pick up gut-damaging worms.

Even a low number of internal parasites can affect cattle health and performance. Cattle with relatively low parasite burdens (324 total slaughter worm counts) have been shown to have depressions in feed intake of up to 3.2%, while cattle with high parasite burdens 1(11,164 total slaughter worm counts) have been shown to have depressions in feed intake of up to 7.8%.

Internal parasites affect the nutritional status of the animal in three ways:

- They decrease feed intake.

- They decrease nutrient absorption.

- They increase nutrient requirements.

These effects of internal parasite infections on the animal’s nutritional status are important because they impact and compromise every aspect of biology – including growth, milk production, immune function and reproduction.

Cattle producers put effort and resources into vaccinating their cattle and offering high-quality feed and mineral programs, but these are not fully utilized and can be wasted if cattle are parasitized.

Strategic deworming’s impact on ADG and weaning weights

A research study compared weight gain, fecal egg counts, parasite enumeration counts and pasture larvae counts over a 99-day summer grazing period of steers on pasture that were strategically dewormed versus a control group.

Steers were randomly assigned to one of two treatments:

- A control treatment with fenbendazole suspension and moxidectin pour-on on day zero

- A strategic deworming treatment with fenbendazole suspension and moxidectin pour-on on day zero, plus fenbendazole pellets on days 29 and 59

Strategically dewormed steers gained an average of 17.1 more pounds over the 99-day study and saw improved average daily gain (ADG) by 0.18 pound compared to control steers. Fecal egg counts were also significantly lower following the treatments on days 29 and 59. At the end of the study, adult gastrointestinal worm counts were 12 times lower in strategically dewormed steers compared to control steers.

It is also important to deworm calves at cowside. When calves start ruminating, they are at a high risk of picking up internal worms. Deworming appropriately from the time of early exposure (from the age of 2 months) can result in improved weaning weights. For spring-calving herds, it typically is good to deworm calves six to eight weeks after turnout onto pasture.

Feed and mineral formulations save time and labor

The good news is there are easy, labor-saving deworming options that don’t require a trip through the chute. Using feed forms of dewormers – such as those found in range cubes, dewormer blocks or mineral – require relatively little time and labor while still being highly effective.

Accurate dosing is critical, not only to give the dewormer the best chance of working effectively but also to help reduce the development of resistance. It is important to follow the label directions carefully and feed the proper amount required for the total number and weight of the cattle being treated.

Free-choice products like blocks (three-day feeding) and mineral (three- to six-day feeding) contain salt as a limiter. After consuming their dose first, the more dominant animals will back off due to the limiter. Then, the rest of the animals will be able to come forward and get their dose.

When administering cubes or pellets (one-day feeding), spread the product out evenly so each animal has a chance to consume the proper dose. If administering pellets bunkside, make sure there’s an adequate amount of space at the bunk for each animal.

Evaluate your dewormer efficacy

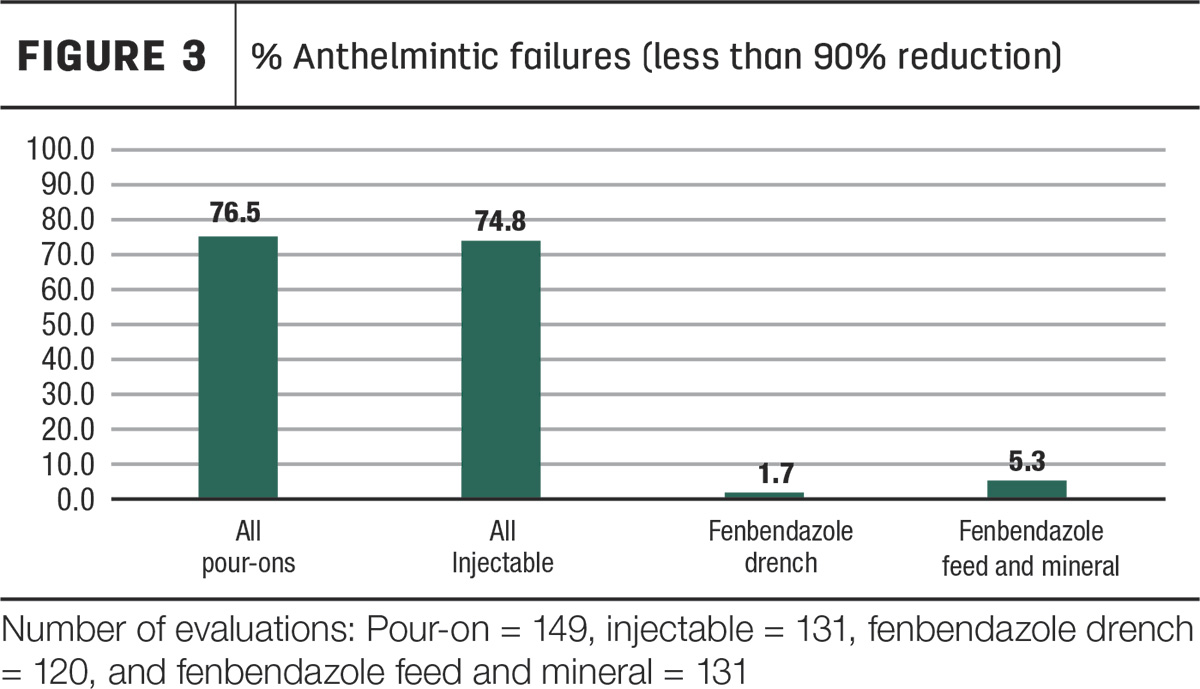

A fecal egg count reduction test (FECRT) is the standardized diagnostic tool to test manure for the presence of internal parasite eggs: 20 samples are taken both at treatment and 14 days post-treatment. Successful deworming should result in a 90% or greater reduction in parasite eggs in feces, but certain classes of dewormers are not working as well as they have in the past.

The largest database of FECRT results monitors the field efficacy of cattle deworming products in the U.S. Today, the database has 14,506 samples from 600 farms; 23 different products have been evaluated.

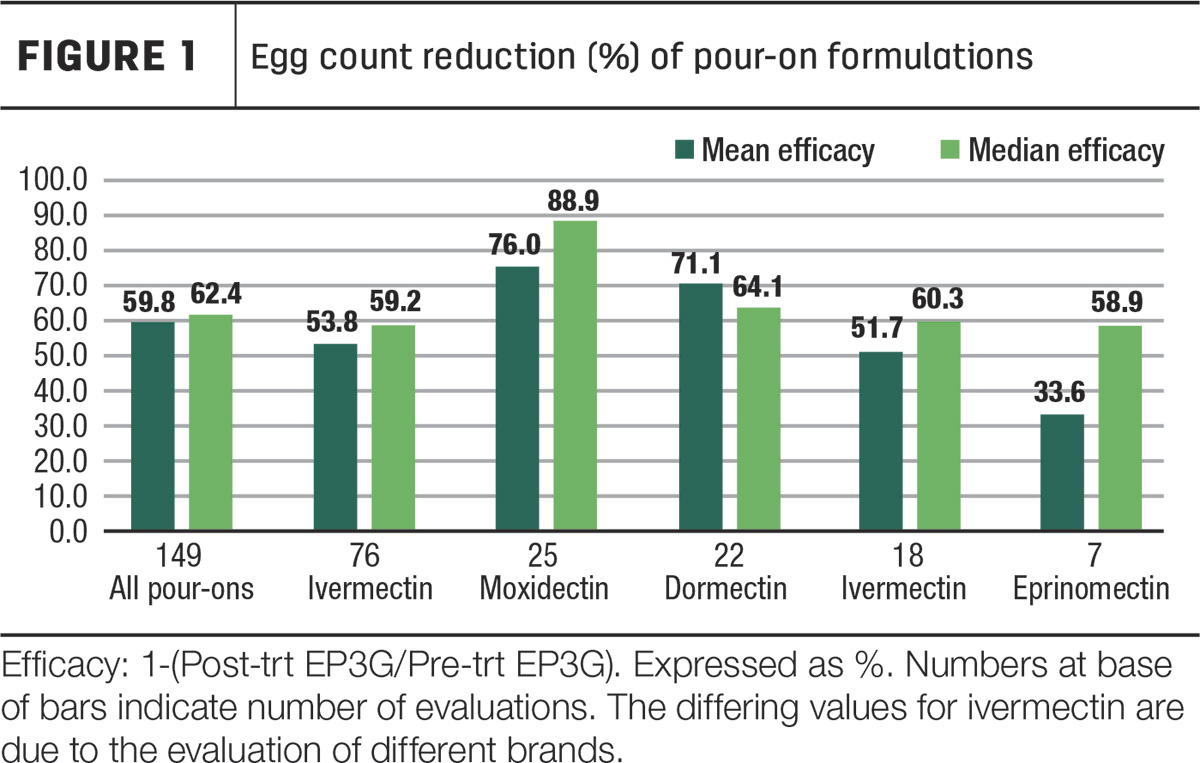

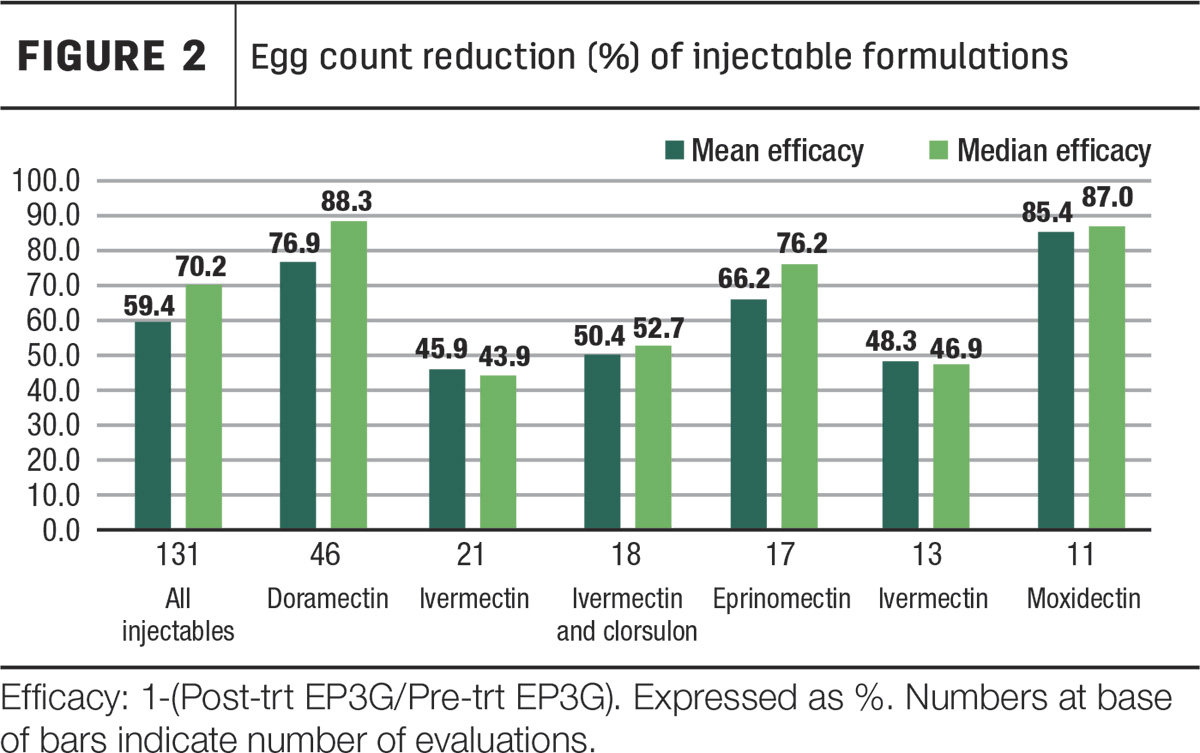

Results based on data through 2023 show that pour-on (Figure 1) and injectable (Figure 2) parasite products have fallen below the 90% threshold for successful deworming. The percentage of anthelmintic failures – those with less than 90% reduction – was 76.5% for pour-ons and 74.8% for injectable dewormers (Figure 3).

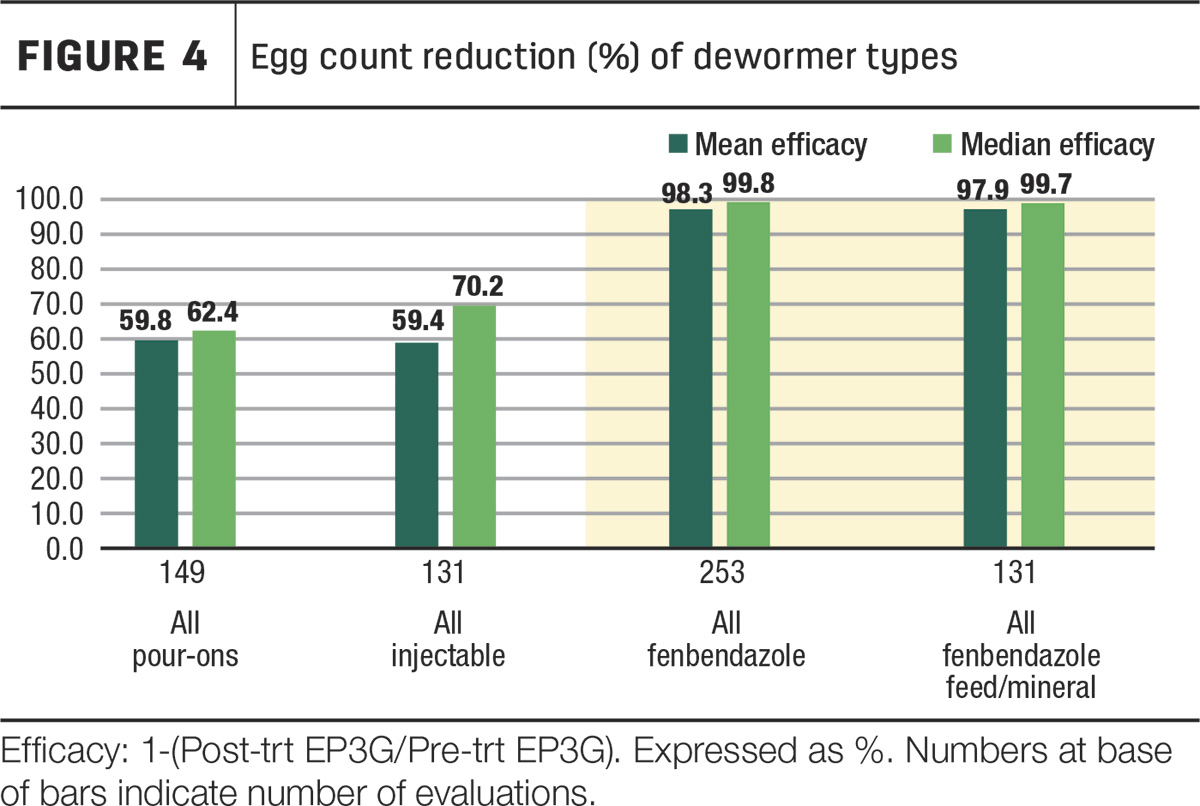

However, all fenbendazole formulations (benzimidazoles class) provide a median efficacy above 99.7% (Figure 4).

However, all fenbendazole formulations (benzimidazoles class) provide a median efficacy above 99.7% (Figure 4).

There is not always a visual sign of parasitism. Unless FECRT testing is conducted, it is unknown how effective the deworming was or the amount of time before reinfection occurs after deworming. Work with your veterinarian to do FECRT testing annually. It is a simple, reliable method to assess efficacy.

To learn more and request a free FECRT kit, visit the Merck Animal Health website. Consult with your veterinarian to assess your deworming program and find the timing and formulations that work best for your operation.