Wildfire, smoke and air quality

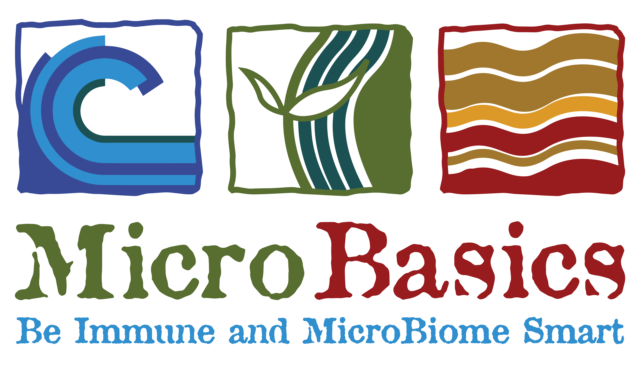

As wildfires increase in frequency, size and duration, more humans and animals are exposed to the resultant smoke and its hazardous effects. Smoke from wildfire is chemically complex, comprising a range of potentially toxic combustion products and fine particulate matter. The composition of smoke depends on factors such as fire behavior, vegetation type, burn conditions and available fuel. The particulate matter (smaller than 2.5 micrometers; [PM2.5]; Figure 1), a mixture of solid particles and liquid droplets found in the air, is the principal public health threat of wildfire smoke. Air quality and the concentration of PM2.5 can be monitored using the air quality index (AQI), which is available at the AirNow website.

Wildfire smoke exposure and its impact on cattle

Wildfire smoke exposure’s impacts have been explored in greater depth in human literature, whereas its effects on livestock are still in the early stages of investigation. One major concern related to inhaling particle pollution involves the body’s reduced ability to remove inhaled foreign materials such as viruses and bacteria from the lungs, making humans and animals more susceptible to other diseases.

A published article reporting the findings of a survey conducted with more than 100 livestock producers in California, Nevada and Oregon shared that 26% of producers reported evacuating livestock, and 19% reported pasture losses as a direct impact of the 2020 wildfire season. Indirect losses from smoke exposure, including pneumonia and reproductive losses, were reported more broadly, and reduced weight gain and milk yield were also reported by the producers.

Natural smoke exposure study

Our group conducted a study to evaluate the effects of natural wildfire smoke exposure on 18 beef-on-dairy calves (Jersey-Simmental) from a commercial farm located in Oregon. Calves were enrolled in the study at birth, and blood samples for analysis of multiple markers were collected before, during and after wildfire smoke exposure in a total of seven collections. Air quality data, specifically PM2.5 near the study location, was obtained from the AirNow database.

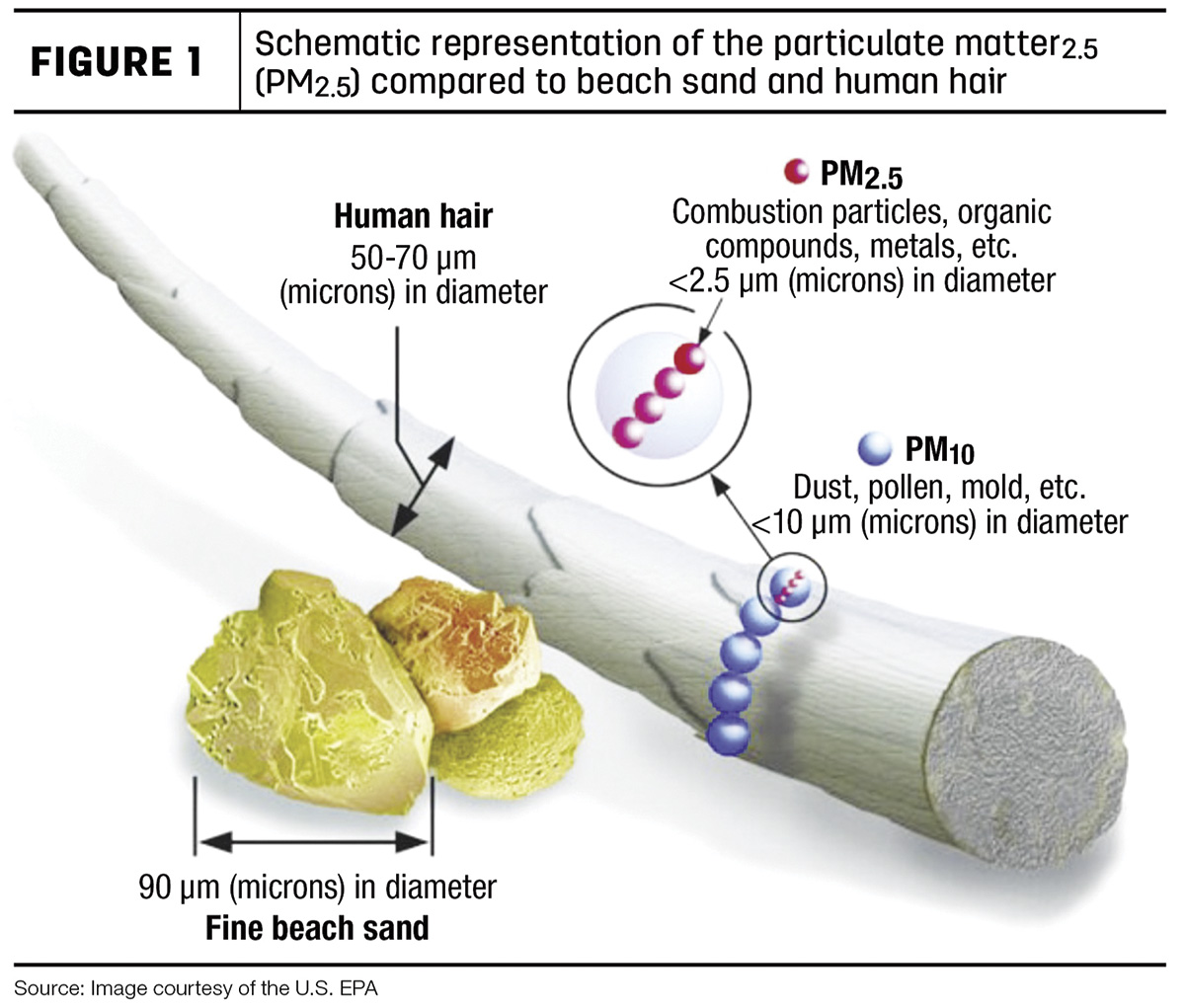

Air quality before wildfire smoke exposure was considered adequate, and PM2.5 was, on average, 4.9 micrograms per cubic meter from June to August. In September, a wildfire event occurring approximately 10 miles from the study location reduced the air quality, increasing PM2.5 to an average of 44.6 micrograms per cubic meter for four consecutive days. After the fire was contained, air quality improved, and PM2.5 dropped to 8.6 micrograms per cubic meter. Therefore, during the study, calves were exposed to four consecutive days of smoke and poor air quality.

The blood cortisol concentrations of samples collected before smoke exposure did not differ at 4.4, 2.0 and 1.9 nanograms per milliliter. Blood cortisol concentrations increased and peaked during wildfire smoke exposure at 10.3 and 7.0 nanograms per milliliter. Immediately after smoke exposure, cortisol concentrations averaged 6.3 nanograms per milliliter, intermediate between those before and during wildfire smoke exposure. Interestingly, blood cortisol concentration averaged 9.5 nanograms per milliliter in the last post-smoke exposure sample, similar to concentrations during the wildfire smoke exposure period (Figure 2).

This increase in cortisol concentration in the last blood sampling was unexpected but likely explained by the calves being weaned two days before this final sampling. The increase in blood cortisol concentration during smoke exposure is concerning and could reduce animal performance and ability to fight other diseases. Furthermore, calves also exhibited alterations in health scores, including an increase in the percentage of coughing and nasal discharge, which could negatively influence calf development.

Controlled smoke exposure study

The previous study was conducted with cattle naturally exposed to wildfire smoke. Our group recently conducted a simulated wildfire smoke exposure study, where we successfully created smoke to mimic air quality conditions observed during the wildfire season.

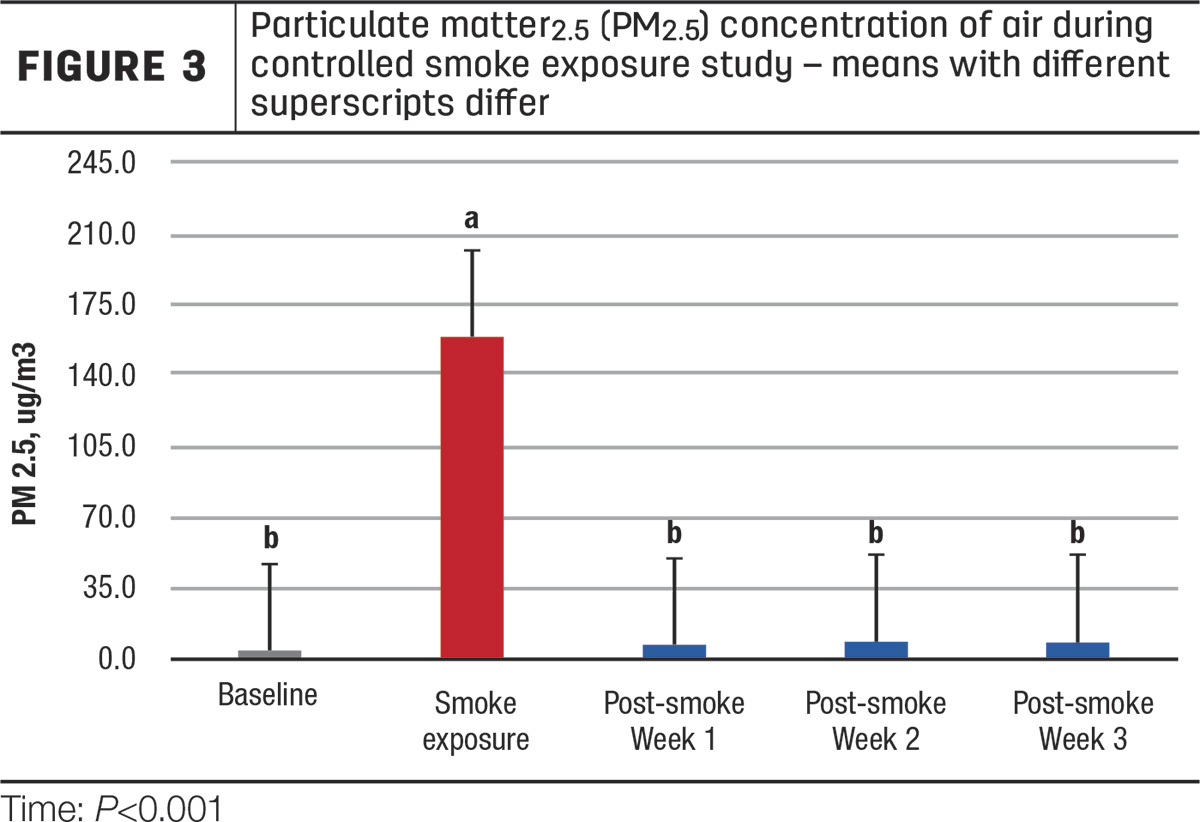

In this study, a wildfire smoke simulation was created to evaluate the effects of smoke exposure on beef cattle health, performance and behavior. Eight 8-month-old Angus-Hereford cross heifers were acclimated to individual pens in a completely closed barn for seven days. Heifers were maintained in the barn for 36 days and exposed to wildfire smoke simulation for seven consecutive days. Thus, the study was divided into baseline/acclimation, smoke simulation/exposure and post-smoke exposure. Blood samples were collected weekly from heifers for evaluation of multiple blood markers. For the duration of the study, air quality was monitored daily every minute using two air quality monitors.

Preliminary data analysis shows that air quality, assessed with PM2.5, changed over time, reaching a daily average of 159 micrograms per cubic meter during the smoke simulation period (Figure 3).

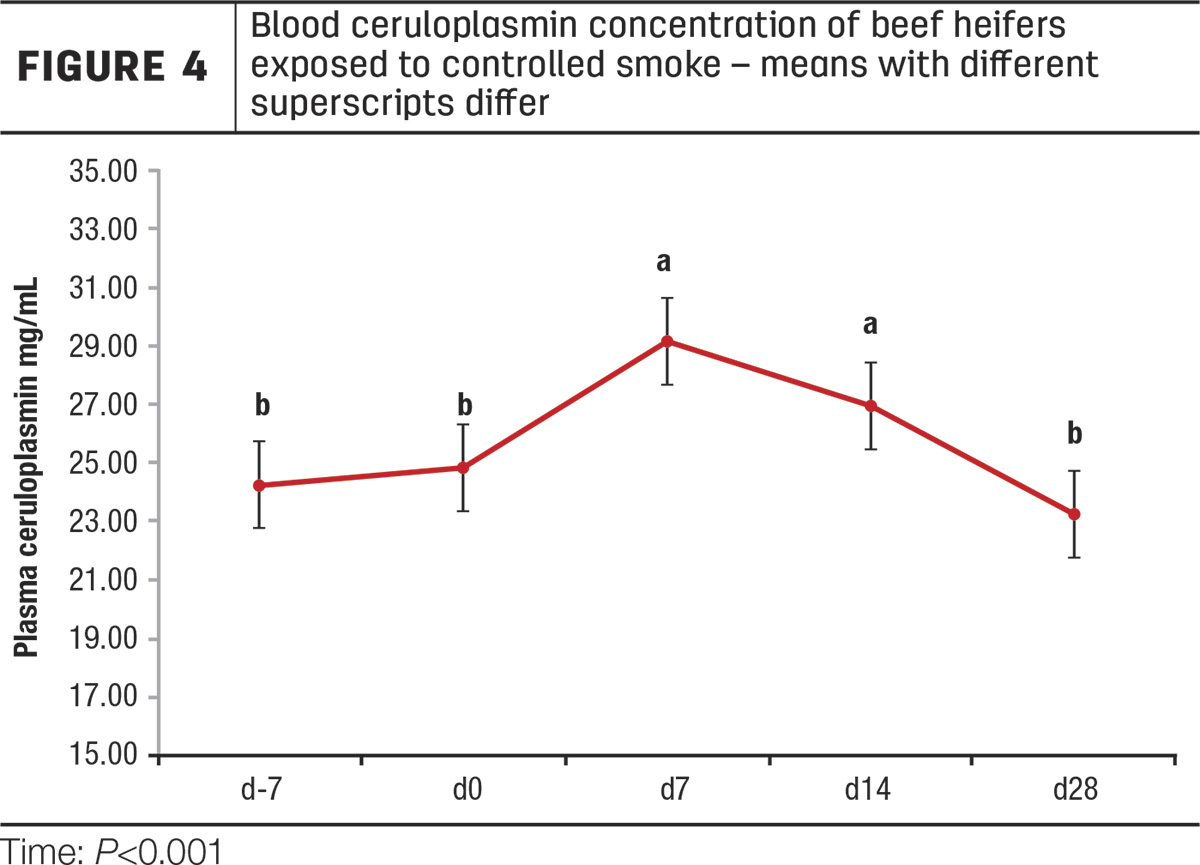

Initial analysis of blood parameters showed that heifer plasma ceruloplasmin – an important inflammatory marker – increased over time, reaching a peak during smoke exposure, which was maintained for a week post-smoke exposure before returning to nadir (Figure 4).

Corroborating with previous data, exposure to wildfire smoke might elicit an inflammatory response, potentially leading to reduced cattle performance, which could be accompanied by changes in behavior, such as decreased feed intake. Our group is currently analyzing additional data from this study, including other metabolic markers and behavioral recordings, to understand the consequences of this environmental challenge better.

Tips on handling livestock during wildfire smoke exposure

According to the American Veterinary Medical Association, common signs of possible smoke irritation include but are not limited to coughing or gagging, difficulty breathing, eye irritation and excessive watering, nasal discharge, asthma-like symptoms, increased breathing rate, fatigue or weakness, disorientation or stumbling, reduced appetite and thirst. Inflammation of the throat or mouth is also noticed when near the wildfire. Animals may show none of these signs and still experience stress from exposure to wildfire smoke.

During smoke exposure, monitor animal health daily and, if possible, keep track of feeding habits; distressed and sick animals often go off feed. Provide livestock with plenty of fresh water located near feeding areas. Proper water intake is essential to keep the airways moist and facilitate clearance of inhaled PM2.5. Dry airways allow PM2.5 to remain in the airways, potentially worsening the symptoms of smoke exposure and eventually leading to opportunistic infections caused by bacteria as respiratory defense mechanisms are compromised. Minimize animal exercise in order to reduce the flow of PM2.5 into the lungs and, when possible, postpone other stressful activities, such as vaccination, weaning, transportation and commingling until the smoke clears. Those management practices are essential, however, known to be stressful and to elucidate an inflammatory response; therefore, postponing such practices to when environmental conditions are not challenging might be best.