Many livestock economists have demonstrated over the years that there is a premium in the marketplace for uniform lots of calves. For further proof, just watch what happens at the local auction market when it comes to selling feeder cattle and then tune in to one of the online video auctions and compare prices.

Even if all else is equal, the larger, often semiload-sized lots, sell for higher prices. Kenny Burdine at the University of Kentucky has shown that lots of 10 outsell lots of three to five head, and those lots outsell single calves. Why discuss this now? As cattle prices remain at historic highs, I am beginning to hear producers question the return on managing reproduction in their cow herds.

Reproduction is the single-most economically important trait on any commercial cow-calf operation. I think it’s time to revisit why that is. There are two main reasons:

- We must have a live calf to sell. A live calf, no matter when it’s born, generates more revenue than no calf at all. This remains true in all instances.

- Cattle producers are in the business of selling pounds. More pounds of calf to market equals more revenue generated per cow.

How do we get heavier calves to market? It’s a combination of improving genetics within the herd (which is never a bad idea), proper animal nutrition (also recommended) and managing a breeding/calving season, i.e., managing reproduction.

Just synchronizing a group of females has great benefits when it comes to creating uniform lots of weaned calves. Add in artificial insemination (A.I.), and we capture some improved genetics.

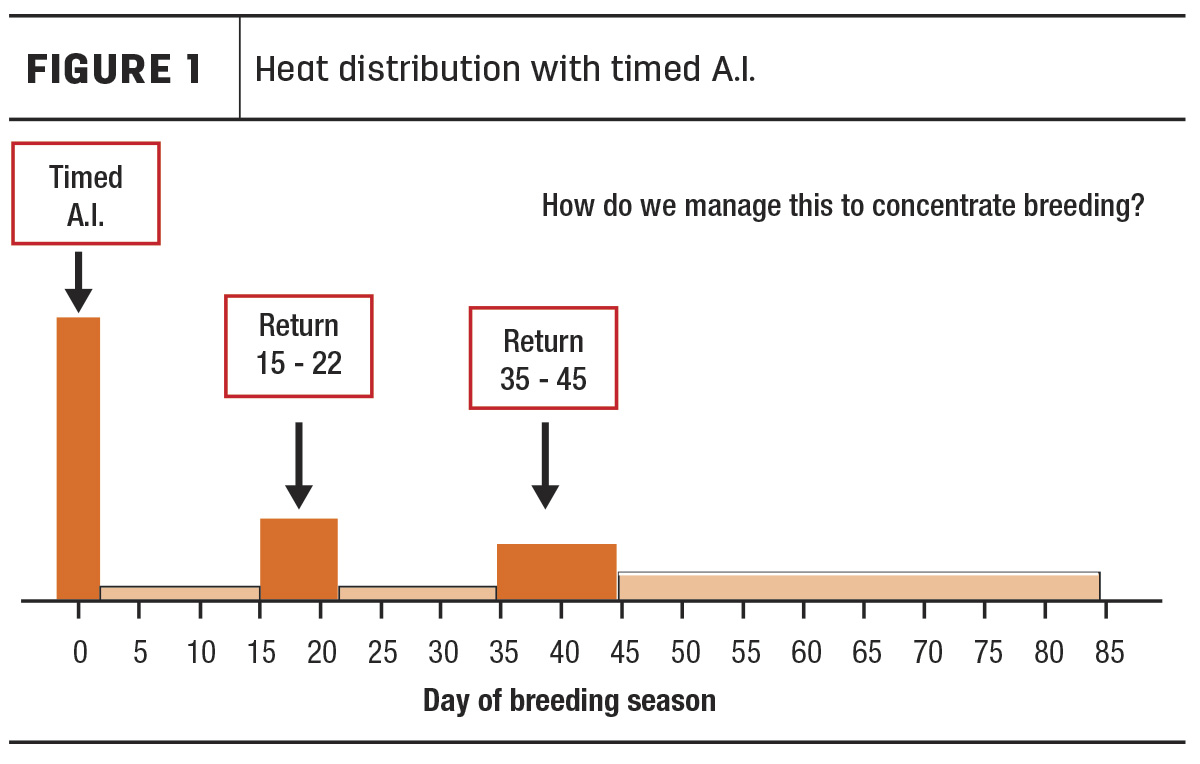

When we teach A.I. schools in Ohio, we spend a significant amount of time talking about fixed-time A.I. breeding for beef cows. The reason for this is to answer the question, what is it worth having 50% to upward of 70% bred on the first day of the breeding season? Many cow-calf producers market a year’s worth of cattle on one day. Therefore, because of how those calves are marketed, they might as well have the same birth date. By using fixed-time A.I., we can tighten up the calving dates for a significant portion of the cow herd.

If we set the entire herd up for fixed-time A.I., those cows who do not conceive to the artificial insemination will be back in estrus in roughly 21 days to either be artificially inseminated again or to be bred by the bull. At approximately day 42 of the breeding season, those females that were synchronized and did not get pregnant after the first two matings should be in heat a third time.

A 45-day breeding window seems short, but if a cow herd is synchronized and bred fixed-time A.I. on day one, that 45-day season gives that female three chances to be bred. Think like a baseball umpire: three strikes and you’re out. Consider culling subfertile cows.

A 45-day breeding window will certainly make for a more uniform calf crop in terms of weight and size, but there have to be sufficient resources and management in place for that system to be successful. First and foremost, cow nutrition needs to be on point. A goal should be to have cows at a body condition score of 6 at breeding. In the hierarchy of nutrient use, reproduction is toward the bottom of the list when nutrients are partitioned. Maintenance, development, growth and lactation all take precedence over reproduction in postpartum cows. Secondly, having enough bull power is key. Can your bulls breed up to 50% of your cow herd on day 21 of the breeding season?

I wouldn’t recommend that a producer with a non-defined breeding window or even a long 90-day breeding season make the immediate jump to a short breeding season. However, working toward a short, defined breeding season over a couple years will lead to a more uniform calf crop at marketing and should improve cow fertility as subfertile cows are identified and culled from the herd.