Crops, like cows, produce more when stress is minimized.

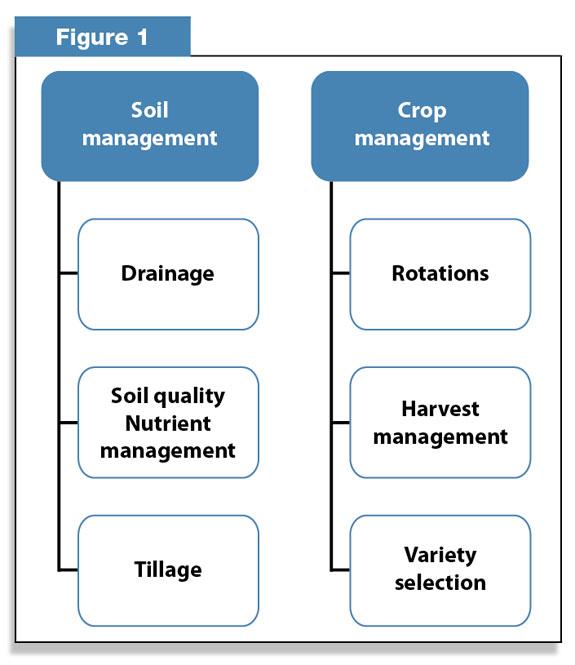

Focusing on fundamental soil and crop management practices will result in a more resilient cropping system capable of weathering the extremes.

Soil management starts from the ground up and with knowing your fields and soil types.

Native fertility and drainage capacity is largely a function of soil type.

One of the most important aspects is adequate drainage.

In poorly drained soil types, inadequate drainage is the biggest factor limiting production potential. While many farms invest in subsurface tile drainage, it is still unamortized on the whole.

Drainage technology continues to evolve and improve. Controlled drainage allows for water table control to reduce nutrient loss during the dormant season and can also be used for subirrigation to increase soil moisture in dry times of the year.

Having control over subsurface drainage may thus offer the best of both worlds in terms of water management.

Soil quality (or soil health) can be defined as the ability of a soil to produce profitable, sustained crop yields while minimizing nutrient loss to the environment.

Soil organic matter (SOM) is probably the most important factor affecting soil quality due to its simultaneous influence on biological, chemical and physical properties. Research and history tell us that losing SOM reduces crop yields.

Organic matter holds soil aggregates together, which maintains good soil structure and pore size distribution, facilitating air and water movement which is key for strong root development.

Where soil structure and tilth are good, erosion is reduced as more water can infiltrate into the soil (compared to poor structure/tilth).

Adequate SOM also helps reduce compaction potential and increases fertility. About 5 percent of SOM is organic nitrogen (N), so more SOM equals greater N mineralization potential. Mineralization of SOM also releases significant amounts of plant-available phosphorus and sulfur.

It is important to note that soil fertility is part of soil quality and that the best fertility cannot make up for degraded soil (e.g., compacted soils, low SOM, poor internal drainage).

Fertility is critical, however. Every farm should have a nutrient management plan to maximize the use of on-farm nutrients and reduce nutrient loss and unnecessary fertilizer purchases. Keeping up on the latest technology may be a chore but it pays off.

If you are not utilizing some of the new nitrogen (N) tests (e.g., Illinois soil N test, corn stalk nitrate test), you are missing out on fine-tuning N applications and increasing N use efficiency.

On the N front, there is also a new tool (Adapt-N) that aims to predict sidedress N needs based on soil, crop and weather information.

Adapt-N is a process-based model developed by Harold van Es and colleagues at Cornell. It is based on many years of field and laboratory research and has the potential to increase N use efficiency, since it factors in the latest weather information in recommending sidedress N rates.

Tillage is another key aspect of soil management. Though many of us may be stuck in a rut when it comes to tillage, there is likely room for improvement.

There is a balance between too much and too little tillage. Too much tillage compacts soils, destroys soil structure and reduces SOM; too little can result in poor seedbed conditions and a weak crop. Knowing when, where and what tillage fits best is key.

For example, most know that no-till is not the answer on every acre, but it does fit on well-drained fields. Well-drained soils tend to be coarser in texture and in need of SOM, which no-till has been proven to increase.

The practical problem with conventional tillage is compaction from implements and tractors. Fall tillage and secondary tillage in the spring is often the norm in the northern states, since fields typically remain wet into May and freeze-thaw cycles help “mellow” clods over winter. However, there are opportunities for reduced tillage on heavier soils.

Zonetill planters use multiple flouted coulters and trash wheels to form the seedbed and are often used in conjunction with a zone builder.

Zone builders are one-pass tillage tools that till small strips where seeds will be planted, thus saving on time, labor and fuel while reducing compaction potential.

Zone builders typically utilize a combination of coulters and subsoiling shanks. Subsoiling shanks or large coulters break up plow pans and compacted zones, allowing for greater root access.

In theory, zone building could replace chisel plowing in the fall – corn could be planted directly into the narrow strips the following spring, eliminating the need for secondary tillage and further reducing compaction potential and soil disturbance.

While more research on zone-till in northern regions may be needed to determine if it is a good fit, it appears to have promise.

From the crop side, it is hard to think of something more critical to success than crop rotation. Effective crop rotations reduce erosion, control pests, maintain soil quality, increase fertility and positively affect the bottom line.

While most farms operate under a conservation plan and follow prescribed rotations, there could be room for improvement.

On fields where soil loss is not a concern, we may lapse into growing corn year after year out of convenience.

If manure is not being applied, soil quality is likely declining. Rotating to a hay crop will begin to restore SOM and reduce pest pressure.

Another opportunity may be cover crops. In a warm fall, there are opportunities to plant a winter cover crop following corn silage. Why consider this? If you are short on haylage acres, a cover crop like winter rye or triticale can provide high-quality forage in early spring and reduce N needs for corn.

Depending on when it is harvested, you may or may not need to plant a shorter-day hybrid.

On wet fields, cover crops will speed up soil drying due to the amount of water transpired. On steeper fields, cover crops reduce erosion and keep more nutrients and SOM on your fields. Cover crops can also reduce weed pressure.

Harvest management is the key to maximizing forage quality and profitability. Good harvest management means harvesting corn and forage crops at the right time and making sure the crop is harvested and stored properly. Monitoring fields leads to harvesting at the correct maturity.

While weather has a lot to do with crop maturation, spending time in the field will assure you of where things are at. We all know the tradeoff between yield and quality.

Being flexible is also important. Each farm needs to determine how to best optimize labor resources with forage quality and inventory needs. Having a well-thought-out plan for harvesting and good communication across the farm can go a long way.

Variety selection is a third aspect of crop management where risk may be reduced. Today’s seed industry can be intimidating if you are unsure of your needs.

Staying on top of varieties and hybrid traits is important (or at least working with someone who does). While there are many good varieties, there is also plenty of room for misinformation.

Talk to more than one person and work with your crop consultants and nutritionist to determine your needs. Think site-specific. Corn hybrids and forage species should be tailored to individual field conditions such as drainage and fertility.

Focusing on soil and crop management fundamentals will lower weather-related crop production risk by reducing crop stress. Keep an open mind and do not be afraid to try something new. Read up on what you are curious about and utilize your own farm as the test plot. FG

—Excerpts from William H. Miner Farm Report, April 2012