Avoid the commodity mentality

First of all, consider the characteristics of the material to be harvested. When ensiled, legumes such as alfalfa and red clover are harder to acidify compared to corn because of the higher concentration of protein, organic acids and minerals, which increases the resistance to pH drop (buffering capacity). More acid has to be produced to acidify (ensile) the crop. In contrast, corn silage is more prone to heating during feedout because of its high contents of starch and sugars.

The use of inoculants, designed and proven, to cope with the challenges you face for each crop and harvest is an effective management tool. Silage quality is one of the single-biggest determinants of profitability. Silages should never be viewed as commodities, but valuable feeds that need to be managed to achieve maximum quality for best performance.

Commercial forage inoculants

Traditional or classical inoculants contain species of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) that convert soluble sugars to lactic acid efficiently (homofermentative LAB), such as Lactobacillus plantarum and Pediococcus pentosaceus.

Products may also contain enzymes to generate sugars to drive acid production (in which case enzyme activity levels should be clearly stated on the packaging). Homofermentative production of lactic acid results in highest recoveries of dry matter (DM) and energy; less desirable fermentations can convert forage dry matter into carbon dioxide, which is lost to the atmosphere, since it is a gas.

Moreover, lactic acid is approximately 10 times stronger than the other acids produced during ensiling (acetic and propionic; therefore it is the most efficient acid for a rapid pH drop. The low pH produced will inhibit plant enzymes that break down proteins; and microbes such as Clostridia and Enterobacteria, which produce harmful compounds and which fermentations result in high DM losses.

The second class of inoculants aims to improve the aerobic stability and feedout characteristics of the silage, preventing dry matter and energy losses and heating in the silage mass or feedbunk. The bacteria in this type of inoculant produce compounds with strong antimicrobial properties in addition to the lactic acid required for the initial pH drop, but which can be a food source for the yeasts that cause aerobic spoilage.

Propionibacteria convert three parts of lactic acid to two parts of propionic acid and one part of acetic acid; however, they are not very resistant to acidic conditions. Consequently, research has shown that successful application occurred mostly in forage crops where the decline in pH has been slow or the final pH was 4.2 to 4.5 (e.g., wheat silage, high-moisture corn).

Lactobacillus buchneri is a heterolactic LAB proven effective in enhancing the shelf-life of silages and TMRs produced using inoculated silages. L. buchneri converts moderate amounts of lactic acid, produced during active fermentation, to acetic acid, a strong anti-fungal compound.

This process occurs slowly during storage time; thus higher application rates compared to traditional inoculants (400,000 versus 100,000 colony-forming units/gram (CFU/g)) have been shown to be reliably effective, allowing a claim for improving aerobic stability to be made following a review of data by the FDA.

Make sure you do the homework

There are a wide variety of microbial inoculants available in the market. Look for a product that contains bacterial strains which effectiveness was tested by independent research institutions and published in journals, such as Journal of Dairy Science and Journal of Applied Microbiology. Remember that there are several strains of, for instance, Lactobacillus plantarum, so make sure that the product has the same strain as the one evaluated in the research study. (Catalog numbers for the strains should be available from the manufacturer, if not already in the product documentation.)

Although two “bugs” may belong to the same species, they likely do not share the same properties and activity. Look carefully for information regarding the bacterial counts, guaranteed viability and shelf-life. (They are live organisms.)

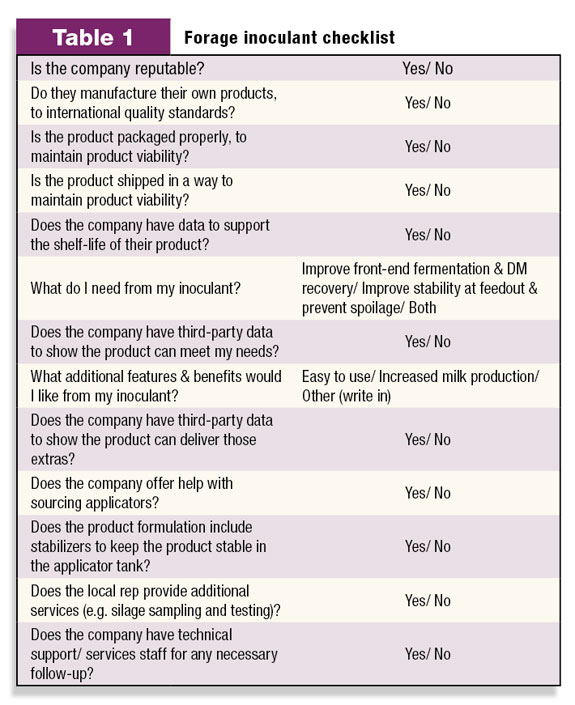

Additionally, freeze-dried bugs are highly sensitive to moisture, thus they should be mixed with an appropriate carrier and packed in materials that block moisture transfer, e.g. heat-sealed foil laminate. If the product is supposed to contain enzymes to drive fermentation, activity levels should be clearly stated in recognized units. A checklist is provided (see Table 1) for additional guidance. Ask potential suppliers plenty of questions – make sure you are satisfied and know everything you want to know.

Do not equate the value of an inoculant with its price

Due to high competition for a share in this market, some companies have adopted low price strategies. Cost should not be the sole deciding factor for choosing a product. The cost of the product inevitably will vary according to the specification, and the type and concentration of bacterial species and enzymes included.

Again, research-tested products indicate the commitment of the company to product quality. Furthermore, some companies are going the extra mile by providing consultants and technical experts to help build detailed silage management plans, to help ensure the quality of silages produced.

In conclusion, determine your needs and decide upon the product to be purchased. If you are employing a custom grower, make sure that the product will be stored properly, applied correctly and that the cost is defined. Keep in mind that you will get the most of the inoculant by starting with forage at appropriate stage of maturity and DM content, and managing the phases of ensiling – harvest, storage and feedout. FG

Robert Charley

Lallemand

Animal Nutrition