Tall fescue is a hearty deep-rooted perennial that grows widely across 15 states in the southeastern U.S. and covers more than 35 million acres. Tall fescue is utilized for its benefits such as drought tolerance and resistance to various insects, viruses and fungal diseases, which are attributed to the presence of a fungal endophyte Neotyphodium coenophialum.

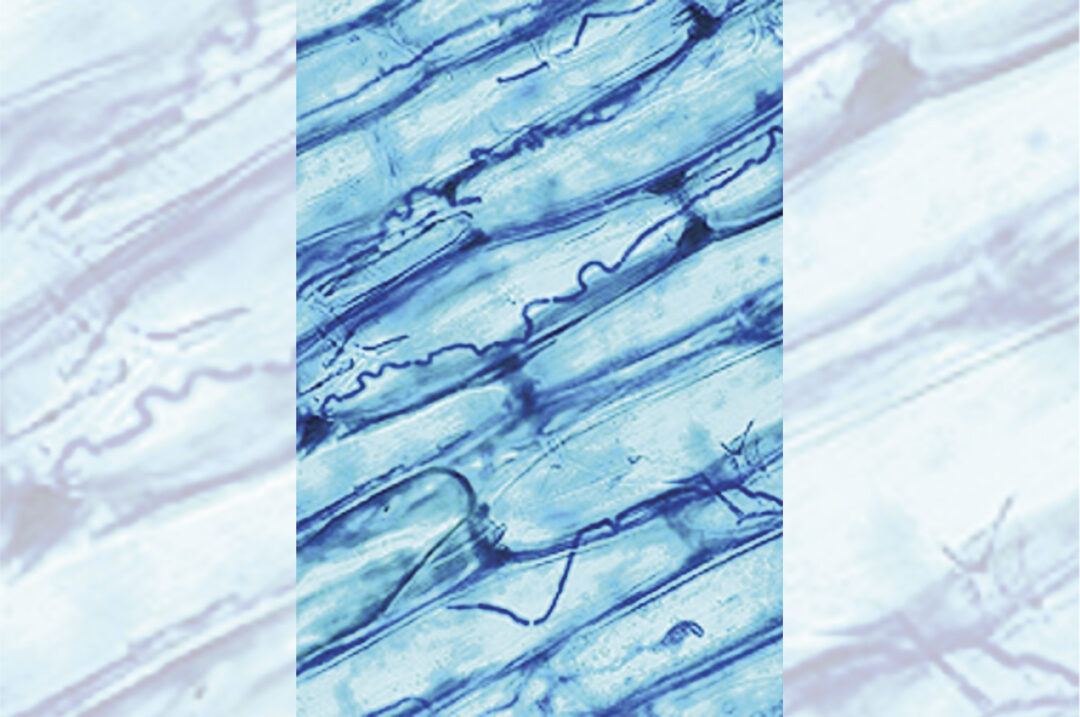

An endophyte is a fungus or bacteria that lives between the cells of a plant. Endophyte-infected plants show no visible signs of infection, and its location within the plant makes it difficult to detect. Since the endophyte fungus is already present at the time of planting, infection will begin to spread throughout the plant as it grows. According to the USDA, approximately 75% of tall fescue forage is infected with this beneficial endophyte, but it can negatively impact your cattle. Although the endophyte helps the plant survive in more adverse conditions, it produces a toxic ergot alkaloid with potent biological effects, which when overconsumed by livestock, leads to fescue toxicosis, which can negatively impact cattle health and productivity.

Ergot alkaloids cause vasoconstriction (i.e., narrowing of blood vessels), which reduces the delivery of important nutrients, compromising multiple organ systems, such as the nervous and reproductive systems. Common signs of fescue toxicosis in cattle include decreased feed intake, reduced milk production, fescue foot (e.g., reduced blood flow to the limb resulting in tissue necrosis) and reduced weight gain.

As a result, performance and reproductive success is negatively impacted, resulting in extreme financial stress for producers trying to combat these issues. Financial implications of fescue toxicosis within the dairy industry are not well understood given the smaller proportion of grazing cattle, but within the beef industry, it has been estimated to cost U.S. producers $2 billion annually.

Dairy producers have growing concerns about the impact of fescue toxicosis on milk production. Fescue toxicosis may cause decreased milk production, or in severe cases, the absence of milk production (agalactia). It is important to distinguish that agalactia and the inability to “let down” milk are very different. If a cow has poor or no milk letdown, milk is being produced but not released from the udder, whereas agalactia is the absence of milk production altogether.

Keep in mind that an udder experiencing agalactia at freshening may appear full because of edema (i.e., fluid accumulation) but still have no milk to be released. Edema can be seen especially in young first-calf heifers and during late gestation, depending on the diet. Currently, no research suggests that fescue toxicosis impacts milk letdown; rather, agalactia may be a result of fescue toxicosis.

Milk synthesis can be broken down into two phases: a lactogenic phase that is at the initiation of lactation and a galactopoietic phase when milk production is maintained over a period of time. Specifically, the ergot alkaloids have the most impact on the lactogenic phase of milk production. Agalactia in cattle affected by fescue toxicosis is thought to be due to a decrease in the hormone prolactin, which results in reduced or absent lactose synthesis in the udder.

The ergot alkaloid from endophyte-infected fescue reduces prolactin by mimicking the effects of dopamine, a hormone known to prevent prolactin release from the pituitary gland. Without prolactin, creation of the milk sugar lactose is reduced or absent from undifferentiated (i.e., nonfunctioning) milk-producing epithelial cells in the udder. Without lactose in the udder, fluid is not drawn into the gland, preventing milk production and leading to empty udders. Without prolactin, a fresh cow entering the lactogenic phase of milk production will have a severely diminished capacity to begin lactation. Fescue toxicosis risk is elevated for dry cows turned out to pasture or springing heifers grazing.

Though agalactia is the primary concern with respect to lactating animals and fescue toxicosis, the disease may alter fat metabolism in lactating dairy cows. A small team of researchers fed lactating Holstein dairy cows tall fescue infected with either a high or low concentration of ergot alkaloids. Cattle fed high endophyte-positive fescue had overall lower milkfat content percentage and lower milkfat yields compared to those fed negative endophyte fescue.

Similarly, another study found numerically lower concentrations of fat in milk during early lactation after Holstein dairy cows were fed endophyte-infected fescue approximately one month before calving. Though these studies were small and results are not conclusive, it is important to be aware of these potential impacts, especially for dairies needing to meet butter fat thresholds for pricing regulated by milk cooperatives and those that operate on a component-based pricing structure.

If there is reason to suspect your fescue pasture is impacted by endophytic fungus, it is best practice to reach out to your local county extension agent or nutritionist to learn about how to collect and send a sample to a laboratory to verify the presence of the endophyte. Once a pasture is confirmed to have endophyte-infected fungus, the following are considerations for management:

- Because the endophyte toxin is present within the tissue of the plant, a method to manage an endophyte-infected pasture is to destroy and reseed it. When replanting a pasture, it is recommended to replant using a “novel” or “friendly” endophyte. A novel endophyte serves as a good alternative because it contains similar positive attributes associated with using endophyte-positive fescue but lacks the detrimental impacts of the ergot alkaloid toxin. A downside to novel endophyte seed is that it costs more per pound than traditional fescue. The Natural Resources Conservation Service recommends reseeding pastures with an infection rate of 60% and higher utilizing novel endophyte. Pastures containing an infection rate lower than 25%-35% are recommended to dilute the pasture by interseeding with legumes (e.g., white or red clover) or other productive grasses (e.g., bermudagrass). Reseeding a pasture can be time-consuming and costly for a producer but can ultimately reduce the financial impact of fescue toxicosis in the long run.

- An alternative management strategy is to limit grazing cattle on fescue pastures in the summer when there is an increased susceptibility to and severity of fescue toxicosis. Cattle are at greater risk during the summer months when alkaloid concentrations in the plant are much higher due to heat and drought. Adding fescue toxicosis as an additional stressor to already heat-stressed cattle can intensify heat-related conditions, which can hinder cattle performance in many areas, especially milk production and rebreeding.

- Another useful strategy to combat fescue toxicosis is mowing. Since the seedheads contain the highest alkaloid concentration, mowing should occur in the springtime. Mower blades need to be set as high as possible to ensure mainly seedheads are being removed, leaving behind at least 3 to 4 inches of vegetative material.

The impact of fescue toxicosis on dairy production is a growing concern for producers who utilize fescue in grazing pastures. Overall, the impact of fescue toxicosis requires more research to better understand its impacts on milk production, milk component synthesis and the financial impact on affected farmers. However, current mitigation strategies can be utilized in improving forage composition on your farm, reducing the impact of fescue toxicosis on your cows and its impact on your bottom line.

References omitted but are available upon request by sending an email to the editor.

Todd Callaway and Lawton Stewart, both with University of Georgia College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences Department of Animal and Dairy Science, and Valerie Ryman, with University of Georgia College of Veterinary Medicine Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, contributed to this article.