Basically, all cows will experience a lower calcium level around calving, and just a small deviation from the normal level can have a larger impact on cow production performance.

This has been confirmed on cows apparently within the normal range of serum calcium level (more than 2.2 mmol per L) in the week after calving.

There is an association with increased odds of displaced abomasum, approximately 3 kilograms per day lower milk yield in the first part of lactation and a reduced reproductive performance observed in a larger number of days open.

Traditionally, dietary cation-anion balance (DCAB) feeding has been applied to dry cows for preventing hypocalcemia. This approach has clearly decreased the level of milk fever problems, but a recent study concluded that more than 25 and 47 percent of primiparous and multiparous cows, respectively, are not able to maintain a normal level of calcium around calving.

Thus, low calcium levels around calving are still one of the major challenges in modern dairy production.

New calcium strategy

A new strategy for improving transition cow feeding is increasing in popularity. The strategy is based on the idea of low calcium supply to dry cows. In order for a low-calcium strategy to work, dry cows need to receive less than 20 grams of calcium per day.

Due to the natural content of calcium in normal feed ingredients, this is basically impossible to practice under typical conditions. Binding calcium in the intestine using a calcium binder in the last two weeks of the dry period is therefore needed to get sufficiently low in calcium supply.

The principle is simple: The calcium binder effectively binds calcium in the feed in the intestine, making calcium less available for absorption.

By doing so, the cow activates stimulation of the hormonal system to allow absorption of calcium from body reserves and to mobilize calcium release from the skeleton.

In other words, we activate the cow’s own natural defense mechanism for preventing hypocalcemia, which makes her able to use calcium from bones and maintain calcium around calving at a natural level.

When ceasing the supply of the calcium binder at calving, the hormonal system is primed and ready to absorb calcium and supply the blood with the necessary calcium.

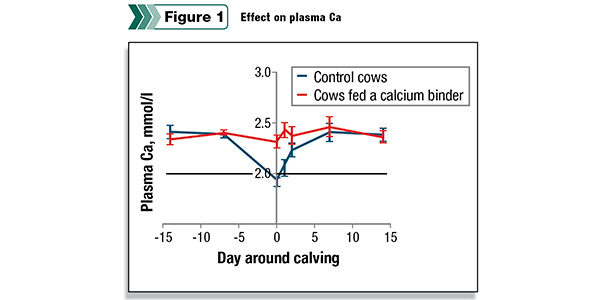

Supplementing a calcium binder in the last part of the dry period has shown to be effective to maintain a normal level of calcium around calving (Figure 1) and decrease both clinical and subclinical hypocalcemia.

Clinical hypocalcemia

Using the calcium binder in the two last weeks before calving on 22 farms which were recognized by veterinarians to have high incidence of clinical milk fever, resulted in 86 percent decrease in milk fever frequency (Table 1).

Subclinical hypocalcemia

Cows having subclinical hypocalcemia do not show typical signs of clinical milk fever and therefore are often overseen on herds.

But these cows not having sufficient calcium levels in blood around calving will be impaired with respect to production and health as the calcium level at calving is one of the most important factors for a variety of other diseases.

On herds apparently not facing big problems with milk fever (about 1 to 2 percent clinical cases), the following effects were found after adding a calcium binder:

- Increased milk production

- Lower somatic cell count for multiparous cows

- Lower frequency of metritis

- Lower culling rate for multiparous cows

- Clinical cases of milk fever were removed

This indicates that well-functioning farms do have a potential for increasing production results by stabilizing the calcium level around calving using a calcium binder.

Potassium concern eliminated

The DCAB feeding strategy implies feeding low-potassium feed to dry cows in order to keep the DCAB value at a correct level. Later cuttings of forage include a high level of potassium and are therefore not seen as appropriate for dry cow feed.

Using a low-calcium approach allows dairy producers to use the same feed components for dry and lactating cows, as the DCAB value is of no importance. An increased liberty in choosing feed components is therefore obtained. PD

This article was prepared in cooperation with Per Theilgaard, senior nutritionist with Vilofoss in Denmark.

References omitted due to space but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.

- Morten Jakobsen

- Protekta