In the last decade, there has been a trend toward adding straw to nutritional programs as a strategy to manage energy density, increase rumen fill, slow the rate of passage of feed from the rumen or increase the level of effective fibre for enhanced rumination.

Dry hay, at times a forgotten ration ingredient, is making a comeback – and we don’t mean only for calves and heifers, but specifically dry cows, transition cows and milking cows.

We can all agree: Making quality dry hay is a demanding process in terms of resources and adapting to meteorological conditions. Therefore, it is not surprising many have chosen to work with straw. However, you may want to revisit your rations and evaluate whether there is a place for dry hay as an alternative forage source.

Getting to know the values

The most common forms of dry hay in rations are grass-based hay (mixtures of timothy, orchard, reed canary, bromegrass, meadows or fescues) or a grass-legume (clovers and alfalfas) mixed hay. Some producers have chosen to work with legume dry hay; however, this comes with the added challenge of maintaining plant integrity from cutting to baling to feeding.

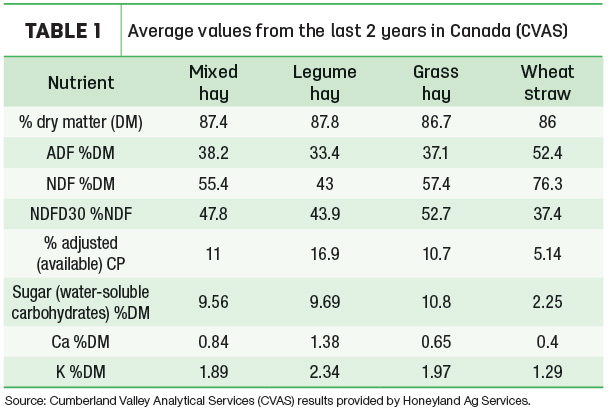

Table 1 compares the average nutritional values of wheat straw and different forms of dry hay over the last two years in Canada.

In terms of nutrient profile, this table clearly indicates the elevated level of fibre in straw. Acid detergent fibre (ADF) is an indicator of the digestibility and energy coming from the forage, while neutral detergent fibre (NDF) is an indicator of potential intake. Ultimately, high levels of ADF and NDF lead to decreased energy intake and digestibility. The NDF-digestibility at 30 hours predicts the amount of a specific forage believed to have left the rumen 30 hours post-ingestion. Depending on your ration, you may require forages that slow the rate of passage.

In a ration that could benefit from a source of fibre, while managing the rate of passage with additional protein, it is valuable to consider a form of hay that may provide two to three times more available protein than straw.

Like protein, adding sugar to a ration comes with a cost. Rations from dry to milking cows require 3% to 7% sugar. A typical dry forage sample can vary greatly in sugar content depending on time of harvest and respiration during the wilting process. Nonetheless, it is estimated that working with dry hay can provide approximately three to four times more sugar than straw. With the elevated levels of soluble protein (rumen rapidly available protein) in this year’s silages, it is valuable to work with high levels of rapidly available carbohydrates (sugar).

Dry hay as an alternative forage source – responding to the cows’ needs and evaluating your margin need to be considered when deciding which source of fibre is the best fit for you. Photo courtesy of ADM.

Dry hay as an alternative forage source – responding to the cows’ needs and evaluating your margin need to be considered when deciding which source of fibre is the best fit for you. Photo courtesy of ADM.Another point we would like to address is the mineral content, specifically calcium (Ca) and potassium (K). Not surprisingly, legume hay contains the highest calcium and potassium levels, while the opposite can be said for straw. Mineral content will have an imperative impact on animal health. For example, a successful transition cow program is linked to metabolic health and prevention of diseases such as milk fever. Therefore, whether you are implementing a low dietary cation-anion (DCAD) strategy with a high-calcium diet or a low-calcium diet for your close-up cows, it is beneficial to work with low-potassium forages, which can be confirmed by representative sampling and wet chemistry analysis.

What is the research telling us?

In today’s dairy industry, it is not uncommon to find straw across the board. Typically, we use straw to increase effective fibre, slow the rate of passage and add a rumen “scratch” factor in milking cow and calf rations, while in dry cow and heifer rations it is used to dilute the energy and slow the rate of passage.

Forage sources can lead to nutritional imbalances. Hays, particularly grass-legume mixes, are more variable in nutrient profile within a field than straw due to the variability of plant populations in the field. Whether you work with straw or hay, it is recommended to use the same batch of forages throughout the year (i.e., manage inventory and storage accordingly).

Researchers in the U.S. compared rations formulated with either wheat straw or grass hay on fresh cow performance. They found fresh cows were eating the same amount of dry matter in each group, but cows fed wheat straw tended to produce more milk and had less circulating non-esterified fatty acids (NEFAs) compared to the cows on the grass hay diet.

The blood concentration of NEFAs is used to evaluate lipid mobilization. NEFAs are produced when the cow mobilizes lipid reserves as a form of energy. Therefore, when the NEFAs in the blood are lower, we predict the cow experiences diminished fat mobilization, which in the subsequent lactation is favourable for reproductive performance and health. It is normal to detect a certain amount of blood NEFAs, particularly in very high-producing herds.

In regards to the study, please take the results with a grain of salt, as the grass hay in the study had a potassium level of 3.1% while straw was at 1.6%. Furthermore, the total potassium level was at 1.9% for the grass-hay-based diet and 1.4% for the straw-based diet. Metabolic diseases were not evaluated, but higher-potassium diets do present greater risks for metabolic health issues like milk fever. Since there are limited studies comparing wheat straw and grass hay in transition cow rations, we cannot provide a concrete conclusion. However, we suggest the success of a nutritional program is based on forage quality and proper balance of fibre, energy, protein, minerals and vitamins as a whole.

For dry hay, we prefer using grass hay instead of alfalfa hay because it typically contains lower levels of potassium, making grass hay a more judicious choice for a well-balanced ration. Certain hollow-stem grasses, such as orchard and timothy, provide a more favourable rumen retention time, which can be beneficial during periods of reduced feed intake (i.e., calving).

As potassium concentration and energy decline with increasing maturity, mature grass hay is the preferred source of forage over an immature form. The longstanding first-cut hay also tends to be faster to dry and harvest, easing management for producers. Furthermore, a first-cut grass hay can be very homogeneous, and a large portion of stems provide the rumen with a desirable physical fibre effect. Nonetheless, it should be noted older prairies (four or more years) will present a lower population stability.

In milking cow rations, we often present wheat straw as “empty calories” – it fills you up, but it doesn’t support much. The main nutrient brought by straw in your ration is effective fibre. To prevent lower milk yields, you must compensate by adding more energy and protein to the remaining part of your ration to reach the same nutrient density; this might slightly increase the amount of concentrates required to meet the cows’ nutritional demands.

Conversely, hay brings effective fibre, and it can provide a respectable amount of protein and sugar. Its fibre is typically more digestible than fibre from wheat straw, increasing the energy available to the cow. Depending on the price or availability of your straw, hay and concentrates, you might want to prioritize one source over another. At the end of the day, responding to your cows’ needs and evaluating your margin should be factored into deciding which fibre source is the best fit for your nutritional program.

Hay from the field to the cow

We are not immune to the challenges brought on by Mother Nature. Making quality hay is dependent on a favourable growing season as well as a window of opportunity from cutting to baling.

To preserve the forage’s nutritive quality, it is imperative to monitor moisture content. You may find yourself in a position where you need to bale at less-than-optimal conditions, with moisture at greater than 14%, which can increase the likelihood of moulds, dust, foul odours and, of course, a loss in dry matter and nutrients due to heating. More specifically, energy loss can be expected since non-fibre carbohydrates are lowered and the level of fibre increased. In addition, protein digestibility is reduced due to the Maillard reaction. The latter can be evaluated through the standard laboratory analysis – ADF crude protein – which indicates the amount of protein damaged because of heating; a value greater than 10% would suggest damaged hay.

When your windrows are ready to bale, even at sub-optimal moisture, it is recommended to work with a hay preservative. This typically comes in the form of propionic acid, which inhibits growth of aerobic micro-organisms leading to moulds and heating. Adjust the quantity of propionic acid to the moisture level (it is ineffective at moisture levels above 30%) – and keep in mind: Large, dense bales are more difficult to dry than small bales. There is a cost associated with propionic acid, but there is also a cost associated with spoiled feed.

If you are in a buyers’ market, we encourage you to visually inspect hay prior to purchasing as well as request a hay analysis. Pay attention to specific sections when reading through the hay analysis. For example, if you are buying hay to incorporate into your milking cow ration, consider the value of available protein, sugar content, minerals (potassium for your milking cows is an asset) and fibre digestibility (the anticipated rate of passage). Lastly, consistency is key; when adding hay to the dry cow and milking cow ration, plan ahead. Will you have sufficient hay inventories to avoid excessive variability in your rations from one month to the next?

Conclusion

Take some time and ruminate on which forage source is the best fit. Sit down and speak with your dairy adviser to see if there are potential opportunities for implementing feeding strategies that include dry hay.

References omitted but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.