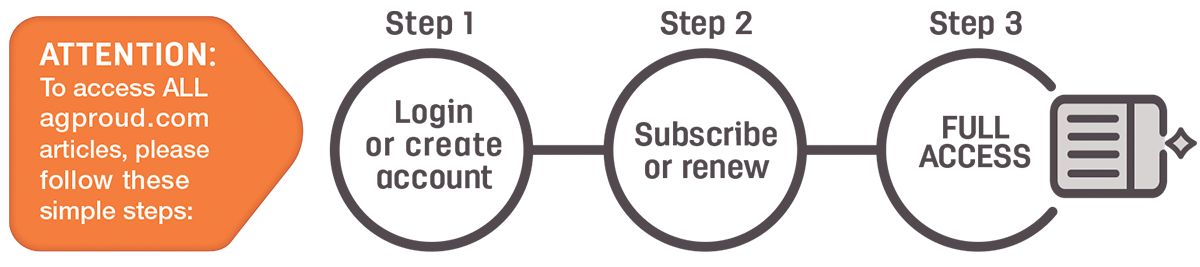

Darn it! This content is only for registered users with a subscription!

Already a registered user? Sweet! Make sure you are signed in.

If not, what are you waiting for? It’s FREE.

Click here to register and create an account.

If you’re having trouble, or would prefer to interact with a human being instead of a computer, please call (208) 324-7513 or email us.

Our circulation department team members will be happy to assist you.