Even though sustainability has been a frequent topic of discussion among animal and natural resource stewards and consumers alike, there remains confusion within the industry regarding what sustainability actually involves.

The topic can surely be addressed from several perspectives. This writing is from a rancher perspective and is intended to offer reminders of practical ways to support ranch and cow-calf enterprise sustainability.

A three-legged stool

A stool with three legs is an effective illustration of sustainability; the legs represent the three most common sustainability pillars – environmental, social and economic. Viability of the stool depends on support and involvement of all three legs. Social and environmental aspects often receive the most attention, especially among consumers and the news media. Economically, sustainable ranches must generate enough income to pay the bills and support ownership and management expectations.

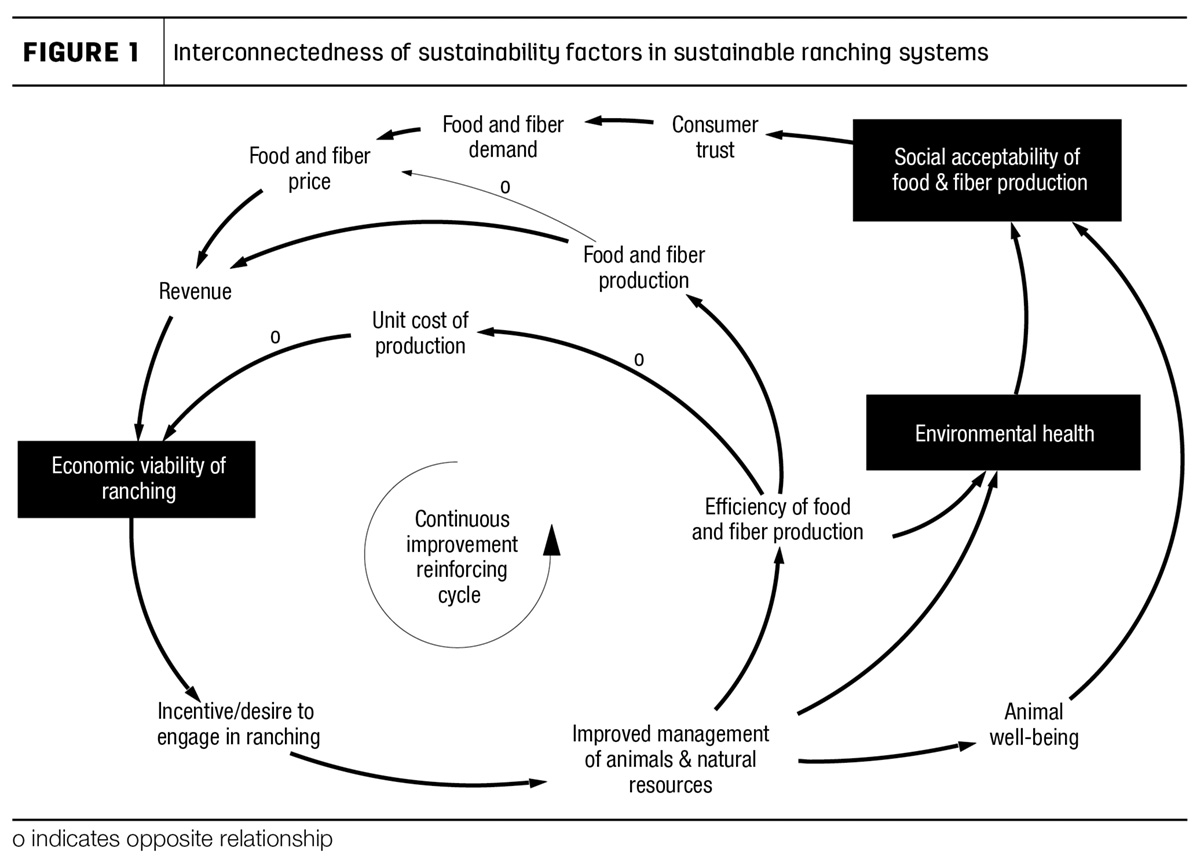

The causal loop diagram (Figure 1) is a visual portrayal of the interrelatedness of the three primary sustainability pillars. An “o” on an arrow indicates an opposite (inverse) relationship between the variables on either end of the arrow. An arrow with no nomenclature indicates the variables are moving in the same (directly related) direction.

The ever-improving management of natural resources and the animals that depend thereon underwrites environmental health and animal well-being, two primary contributors to the social sustainability and societal acceptability of food and fiber production.

The sustainability of all agriculture begins with the soil, its ability to capture water and provide nutrients to support plant growth, while the sun provides the energy that drives the system. The first job for ranchers and farmers alike is to be sound stewards of the natural resources entrusted to our management. Stockmen are called to manage grazing in a manner that facilitates regeneration of the soil and plant communities that feed creatures who live below, on and above the soil surface.

Regenerative grazing is often represented as requiring numerous pastures and frequent herd moves to sustain and improve natural resources. Such management is absolutely a viable option but not the absolute or only choice. Some large-acreage Great Plains ranches have been sustainably grazed for over a century with continuous or simple switchback systems. Deployment of a long-term sustainable stocking rate that protects soil integrity and plant health and productivity is the foundation of any grazing system.

The economic pillar

The economic pillar for any beef producer (cow-calf, stocker and feedyard) centers around unit cost of production. Management decisions that lower unit cost of production while maintaining or improving production contribute to economic success. Diversification of profit-seeking ranch enterprises is a proven means by which to lower weaned calf unit cost of production. Spreading ranch fixed costs across more than one enterprise (e.g., adding wildlife, renewable energy, ecotourism, timber, etc.) lowers cost of production for all enterprises – hence, the reason stocking rate (number of cows bearing ranch fixed costs) is also a contributor to cowherd economic sustainability.

Forage demand, expressed as stocking rate, is primarily a function of animal size; secondarily, nutrient demand is influenced by cow physiological status and desired weight change. Results of several university studies, like the work by David Lalman from Oklahoma State University, that evaluated mature cow size in environments where nutrition is often limiting, give the production and cost advantage to moderate-sized cows with moderate nutrient requirements. Raising or purchasing such cows is a genetic selection choice. Genomics has improved the accuracy of that selection process and will continue to do so.

Fed feed (e.g., hay, silage, protein and energy supplements) is almost always among the top three cow-calf direct/variable costs and offers an opportunity for cost reduction. Selecting cows that are well adapted to the environment and production system in which they are expected to produce results in reduced fed feed and labor requirements, reduces weaned calf unit cost of production and thereby improves sustainability.

Note that mineral supplementation was not included in the short list of fed feeds. Minerals can be the first limiting nutrient for range and pasture forages that support beef cow herds. Consequently, investing in mineral supplementation often yields the greatest return on fed feed investments.

Factors that improve cow-calf enterprise performance are continually emphasized in this and other beef industry publications. The influence of cow herd reproductive performance is huge. When calculating weaned calf unit cost of production, annual cow cost is divided by percent calf crop weaned (as a function of the number of cows exposed for breeding); dividing by anything less than one makes the outcome larger. Reproductive performance and unit cost of production are inversely related.

Cows that conceive early in the breeding season calve earlier and wean older and heavier calves. Heavier typically means higher value per head. Older, in combination with a sound preventative herd health plan, usually means less morbidity and mortality, thus adding to enterprise sustainability.

Costs associated with maintaining ranch infrastructure (roads, fences, water, handling facilities, vehicles, equipment, housing, etc.) require annual attention by ownership and management. Electing to defer maintenance is a short-term remedy to reducing expenses and improving ranch profits but may threaten ranch sustainability. Length of deferment and severity of the consequences are directly related; the longer required maintenance is deferred, the greater the sustainability consequences.

While on the topic of infrastructure, another practical means by which to reduce cost and improve ranch sustainability is conscious and effective management of depreciation. Though not a cash cost, depreciation is generally among the top five largest ranch costs and an appreciable contributor to weaned calf unit cost of production. Cows with greater longevity help reduce the depreciation burden by remaining in production for several years after they have been removed from the depreciation schedule. Annual review of the depreciation schedule used by the ranch accountant often reduces total depreciation cost without saddling a horse, starting a pickup or leaving the ranch office.