As a beef producer, sustainability is defined as your continued ability to live comfortably, to maintain a way of life you have chosen for yourself and to ensure that you can pass that way of life on to your children and your children’s children.

Unfortunately, not all consumers see it that way. And there’s a lot more of them than there are producers like you, so it’s important that you also keep in mind how they define sustainability and what possible impacts that may have on your business’s ability to stick around for the long term.

Consumers have learned by way of social media that sustainability is defined by all activities that avoid the depletion of the planet’s natural resources in order to maintain an ecological balance that promotes the health and well-being of the planet. Unfortunately, both beef and dairy production have been labeled as prime suspects in upsetting that apple cart by causing the apparent ecological unraveling that is being associated with everything from a fast-food hamburger to a quart of milk at the grocery store. It’s consumers and their perceptions – rather than economic realities – that catalyze both market and political change.

In terms of government, the response often is to legislate changes that address consumer concerns regardless of whether these changes make sense or come at the expense of a minority.

A worldwide issue

An example of government reaction is proposed legislation in Ireland that could lead to the slaughter of up to 200,000 cows in Ireland to meet the European Commission's methane emissions standards. This is an effort that’s part of the European Union's (EU) agenda to promote European sustainable agriculture.

Additionally, in a recent United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) publication, the authors suggested that one of the strategies to achieve methane emissions reduction goals as part of the march toward a global sustainable ag model was to encourage the shift toward plant-rich diets, besides away from beef in high-income countries, like the U.S.

Although we have not seen any legal proposals in the U.S. as draconian as the Irish solution, nor have we yet to see legislation whose objective is to discourage beef consumption, our industry needs to be proactive.

Trouble is, industries tend to respond to consumers’ perceived concerns by focusing on short-term strategies that promote healthy bottom lines and exploit marketing opportunities. Unfortunately, these strategies seldom provide either short- or long-term solutions that share wealth with the rest of the supply chain.

For example, in the U.S., retailers of meat, milk or eggs are making sizable investments in developing marketing strategies based on claims that their particular branded product is produced using environmentally sustainable practices, knowing full well that claims like “reducing the carbon footprint” are concepts that are not well understood by consumers and, as a consequence, can be supported in many cases by abstract evidence of compliance.

Admittedly, we have to start a dialogue with consumers somewhere, but current stabs at developing a sustainable business model that satisfies the needs of both the producer and the consumer are still ideas on paper and not in practice.

To add insult to injury, many of these efforts can saddle the producer with the financial cost and moral responsibility to support these assumptions without the benefit of the profit sharing that results from offering the public a guaranteed, value-added product.

The cattle industry must take the lead

Whether you make your living as a cow-calf rancher or feedlot operator, or any combination in between, we are all painted with the same brush by critics pushing the idea that beef production is a key factor in problems like global climate change. Many in the media often conclude that anyone who makes a living raising cattle is partially to blame for climate change. These critics preach a loud-and-clear message that if the demand for beef and dairy went away, the need for the cattle industry would go away with it, and the world would be a better, healthier place as a result.

These critics ignore the fact that the global demand for high-quality animal protein is increasing. They also do not understand that a significant percentage of the global landmass is unsuitable for anything other than ruminant agriculture. And perhaps most importantly, they discount the reality that a significant percentage of the global population is dependent upon beef and dairy products.

Although there may be some truth to the assertion that ruminant agriculture does contribute to the atmospheric buildup of greenhouse gas and the role it plays in climate change, science is now opening the doors to a very workable and sustainable solution.

It starts and ends with fixing the cow.

Over the past 30 years or so, cattlemen have lived through a revolution that has impacted how they make herd management decisions. DNA and genomics testing have helped create a more tangible “blueprint” to follow in making those decisions.

The challenge is that the use of genomics and DNA testing has ignored the limits set by physiology because these technologies have helped to maximize production while often sacrificing efficiency. This has resulted in animals that are “non-sustainable” to certain environments, less disease resistant, more susceptible to stress and, as a population, less biologically successful than the general population of just a few decades ago.

There remains, however, a small population of cows that have continued to be reservoirs of desirable traits and their associated physiological expression that make them winners in our effort to make our industry more sustainable. The added good news is that these “super cows” also turn out to be very profitable while also being the poster children for sustainability.

Gaining new advantages

Over the past several years, I have been part of a team developing a way to identify these super cows. Our method originated from an adaptation of a technology developed and used in human medical research. This technology, trademarked under the name Promogen, measures the concentration of three previously unknown proteins produced by certain cells in the body. The proteins, called defensins, predict the concentration, duration and level of energy-producing activity in each cell in the body. The more available cellular energy is, the greater the productivity of the individual as a whole.

In cattle, this manifests itself in a number of ways. For purposes of this discussion, let’s focus on the highly positive correlation between Promogen-determined defensin concentrations and feed efficiency and relative feed intake.

Controlled research has clearly shown that feed-efficient cattle produce less methane. They produce less manure. And they consume less water.

That’s good news because beef operations that use less feed and less water can’t help but be more profitable through becoming more sustainable.

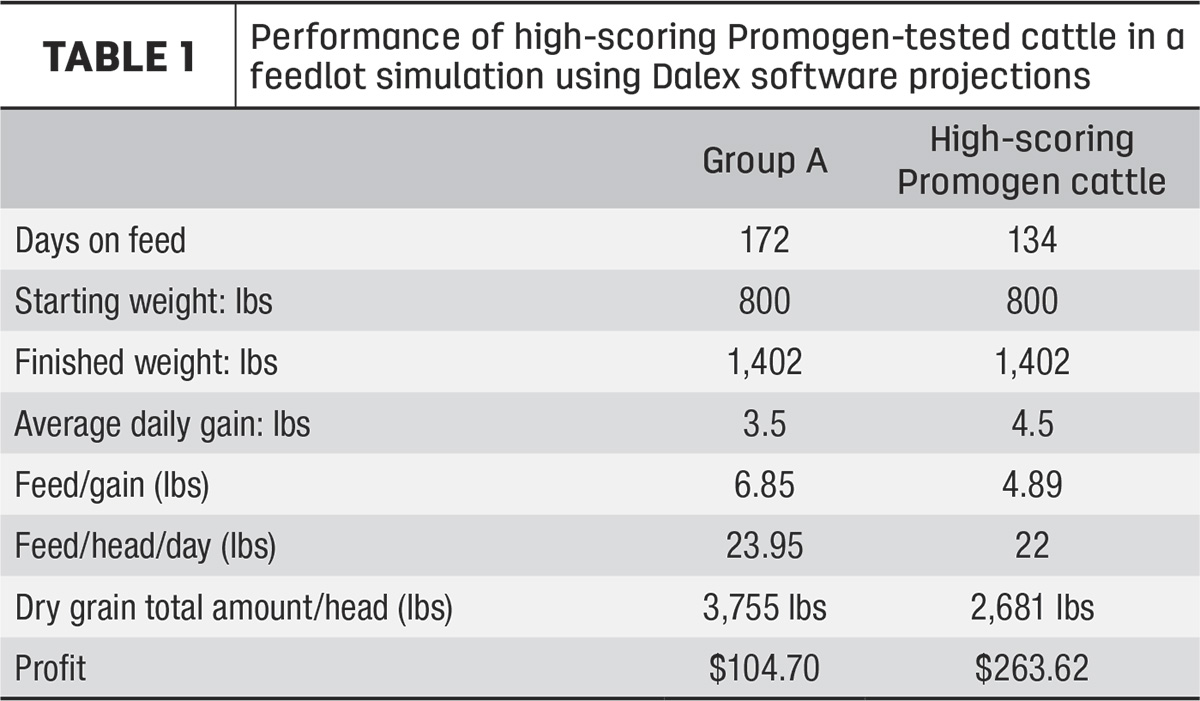

In a controlled, independently conducted 90-day study, the correlation between Promogen score and feed efficiency was recently validated. In this study, 150 commercial Angus bulls, heifers and steers were housed and fed using a GrowSafe testing protocol. The performance data were then inputted into the Dalex Consulting Nutritionist software program that is designed for ration balancing and modeling of feedlot performance economics. This provides precise predictions on days on feed, dry matter intake (DMI) and production costs.

Two projections were then simulated using current live cattle and commodity costs. Projection A was based on current average performance as reported in Markets Insider and two other industry sources. Projection B was based upon similar commodity and cattle costs but used the reported feed efficiency and daily gain data generated by the high-scoring animals. The results are summarized in Table 1.

In this trial, high-scoring Promogen-evaluated cattle reached a finishing weight of 1,402 pounds and did so in 38 fewer days. They had an average daily gain (ADG) advantage of 1 pound, a feed-to-gain advantage of almost 2 pounds and, most importantly, they generated $158.92 more profit per head than the industry norm.

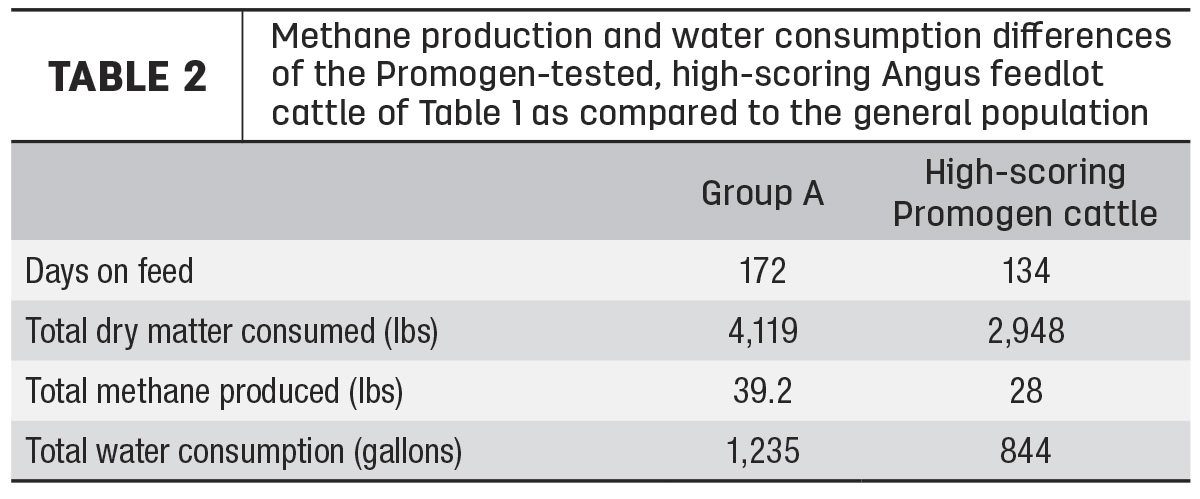

Using the “hybrid model” of estimating supply chain emissions, sustainability is determined by a combination of producer-specific data (as available) and filling in the gaps with average data.

If we apply the results summarized in Table 1, which are specific for Promogen high-scoring cattle, with industry accepted average data, it becomes possible to determine the environmental advantage high scorers have as compared to the average population. These data are presented in Table 2.

Critics focus on methane production and water consumption as arguments supporting the unsustainability of beef production. In this simulation, using the hard numbers reported in Table 1 and average data used by those same critics in calculating supply chain emissions, high-scoring animals generated 11 pounds less methane and drank 391 gallons less water than the average population. This is a 30% reduction in the production of methane and consumption of water, the two main sore spots of industry critics.

The bottom line

Like it or not, sustainability, as defined by the consumer, is not going away, and it will impact the way cattle producers will do business in the future.

There are a variety of outcomes that can result from how this plays out – and whether they positively or negatively impact an operation’s bottom line. The producer must actively and visibly control the narrative.

By using new technologies to more effectively capitalize on the progress we have already made in genetic selection, animal management and environmental stewardship, we can earn the respect and trust of the 320 million people who are our customers.

We are, after all, the original stewards of the land, for if we were not, we’d be out of business.