Dairy and other agricultural producers confront a variety of risks in running their operations. This article will focus on price risk, specifically on the output side – that is the price of milk received. Over the past three decades, U.S. agricultural policy has begun to dismantle the myriad of support programs for basic farm commodities that have existed since the Great Depression.

As a consequence, the past few Farm Bills have provisions that emphasize the need to produce based on anticipated market returns as opposed to adhering to any federal program.

The large government stockpiles of many agricultural commodities, such as grain and powdered milk, seen in earlier years have been sharply reduced. While there is no longer a need to maintain costly inventories, there is no cushion of supplies should a production shortfall occur.

These two factors have contributed to increased volatility for both feed and milk prices. More recently, U.S. milk prices are also being influenced by global supply-demand considerations as foreign trade accounts for a growing share of our domestic production.

For all dairy producers, the most favorable scenario is when milk prices are high and feed prices low. There are times, however, when milk prices are depressed and feed values are very expensive. An extended period of such conditions can cause severe financial hardships and jeopardize the viability of the operation.

There are a number of tools producers have at their disposal to help manage these price fluctuations, including cash forward contracts and exchange-traded options and futures for both the feed input and the milk output risks. It is incumbent that producers employ better use of the price risk management tools that currently exist.

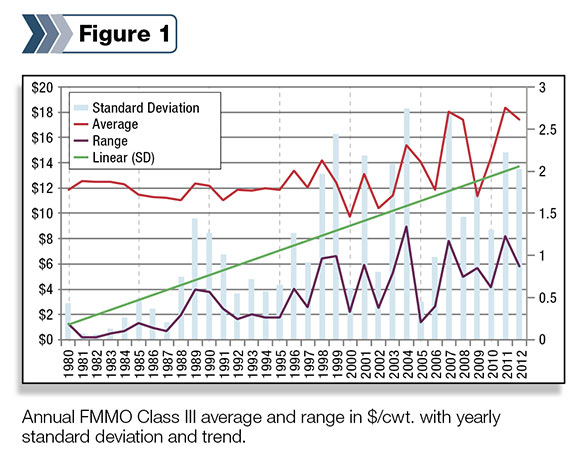

Figure 1 shows the average annual Class III price along with the yearly range in dollars per hundredweight (cwt). Also included is the standard deviation, a measure of volatility and the trend for standard deviation.

Prices traded in a fairly narrow range through most of the 1980s and 1990s, but starting in 2000, average prices have moved higher along with the range of values from low to high.

Standard deviation has also increased as evidenced by the rising trend.

The upshot is that while higher prices, in some cases record milk prices, have been seen in recent years, very depressed values have also been experienced.

This huge range in prices, along with their increased volatility, has created many hardships for today’s dairy producers, especially combined with record feed prices.

The purpose of this article is to compare returns of producers who employed various risk management strategies on the output side versus those that just sold milk on the spot market.

For milk values, the federal order Class III price was used and it was assumed that unless the producer engaged in some sort of forward contract, the milk price received was the monthly Class III value.

The forward contracting benchmark was the five-year rolling average plus one standard deviation of the Federal Milk Marketing Order Class III monthly cash price.

This benchmark was chosen so the producer could, if possible, sell milk at values in the upper one-third of the range in prices seen over the past five years.

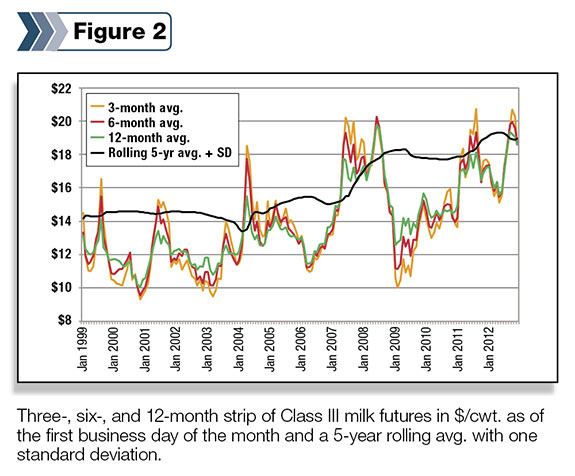

For forward contracting purposes, the nearest 12 months of Class III futures contract data along with the three-month, six-month, and 12-month strips (consecutive months) of futures were used.

Click here or on image at right to view it at full size in a new window.

Click here or on image at right to view it at full size in a new window.

Two separate forward contracting models were devised: one that used strips of futures (Strips Months Model or SMM), and the other that used the individual futures months (Individual Months Model or IMM).

If either the individual months or strips of futures exceeded the forward contracting benchmark, then a forward contract was initiated; otherwise, the actual cash Class III price was used. Data from the Class III milk futures contract traded at the Chicago Mercantile Exchange was used to forward contract milk.

The criteria for contracted milk prices here was the rolling five-year average plus one standard deviation using either strips of futures or individual months. If offered a good forward contracting opportunity, that price was locked in for as long as possible.

A review of the data shows that using the five-year average plus one standard deviation for milk allows for a number of forward contracting opportunities.

While recognizing that total returns are very important, part of the reason some operators forward contract both milk and/or feed is to reduce the variability in these returns. While forward contracting milk or feed may actually result in less favorable prices than if one were to rely on the spot markets, the reduced volatility in prices may be a desired goal.

A strip is consecutive futures months averaged together, and one can actually execute a strip trade on the floor. If the futures price for any particular month or strip of months is above a certain level, then the producer will forward contract all or a portion of that month’s estimated production.

Otherwise, the producer will just receive the cash price, which in this case is the monthly FMMO Class III value. Starting in January 1999, the three-month, six-month and 12-month strips were compared to the benchmark. If the 12-month strip were equal to or greater than the benchmark, 50 percent of the milk for the next 12 months would be sold at that price, with the other half priced at the spot or cash Class III value.

If the 12-month strip price was below the benchmark, the six-month strip was examined to see if it was equal to or greater than the benchmark. If so, 33 percent of the milk for the next six months would be sold at that price, and the other 67 percent priced at the spot or Class III value.

If the six-month strip price were below the benchmark, we would see if the three-month strip was equal to or greater than the benchmark. If so, we would sell 25 percent of the milk for the next three months at that price and price the other 75 percent at the spot or monthly BFP value.

Finally, if neither the 12-month, six-month or three-month strips of futures were above the benchmark, we would just default to the spot price. Our rationale for using different percentages was that we were more willing to forward contract larger amounts of milk if the forward contracted price was attractive.

The other forward pricing scenario is Model 2, where a producer can forward contract any or all of the 12-month’s worth of futures prices at the beginning of the month. If any particular month is over the assigned benchmark (five-year rolling average plus one standard deviation), 100 percent of that month’s production is priced at that point.

It is assumed that any listed price at the beginning of the month can be forward contracted, though not more than 100 percent sold for any month. There are times when, at the beginning of the month, none of the values for futures contracts over the next twelve months will be over the assigned target level and there will be instances where perhaps all months are.

Figure 2 plots the three-month, six-month and 12-month strip of futures and the benchmark price needed to contract.

The study period was from January 1999 to December 2012, accounting for 168 months.

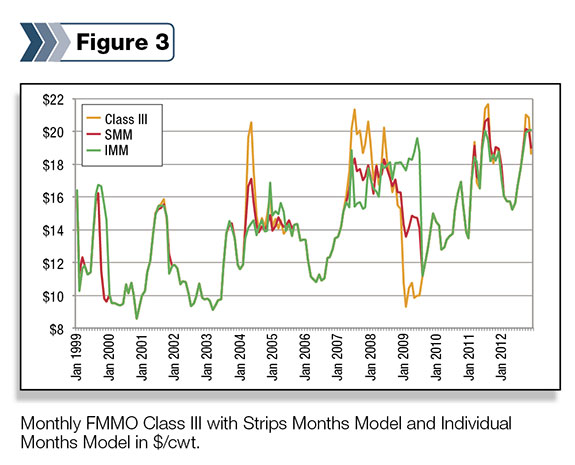

The average Class III price during that time was $13.96 vs. the $13.95 for the Strips Months Model (SMM) and the $14.13 for the Individual Months Model (IMM).

Just using the spot Class III price resulted in higher volatility, as evidenced by the higher standard deviation (SD) and coefficient of variance (CV), which is the standard deviation number divided by the average times 100.

The correlation of the Class III to the SMM prices is 95.0 percent, while the correlation of Class III to the IMM was quite a bit lower at 80.0 percent.

Curious to see how the pricing relation and volatility has changed over the years, the study period was divided into two seven-year periods, January 1999 to December 2005 and January 2006 to December 2012.

For the earlier period, just taking the spot price would have netted a higher average price of $12.29 vs. $12.16 for the SMM and $12.13 for the IMM, though the volatility was higher. The correlations were also quite tight, particularly for the SMM at 98.0 percent.

The latter time period had different results, with the average Class III price higher than the SMM but lower than the IMM, though both forward contracting models had lower volatility with SD and CV values below those of the Class III.

The correlations were also quite a bit lower especially for the IMM. One final comment was that using the IMM resulted in 66 of the 168 study period months being forward contracted, while 71 of the 168 months were contracted using the SMM.

The vast majority of dairy producers are price takers, feeling that since they receive a milk check every month, they will get the average price for the year.

Furthermore, the cash forward milk contracts offered by the various processors and creameries or even the milk futures contracts and options are relatively new, with most producers and their lenders and accountants having very little understanding of the mechanics and concepts of pricing their milk for future delivery.

There have also been a number of academic studies showing that staying on the spot market achieves higher average milk prices than the various methods of forward contracting achieve. Very few if any dairy producers would be willing to accept a price lower than the average.

On the other hand, forward contracting does reduce the range of prices received, dampening volatility of values, which in addition to low prices is another problem today’s operators face. We often think of a baseball analogy where one team has a bunch of sluggers that either hit a home run or strike out.

Figure 3 , showing the Class III, SMM and IMM values, does show that neither of the forward contracting models captures the highs that in recent years have topped the $20 level.

On the other hand, it does protect against some of the extreme lows seen in recent years, particularly the dip below the $10 region back in 2009.

Perhaps small ball may be the better way to go: single, walk, sacrifice bunt, etc.

It may not be as sexy as swinging for the fences, but it will keep you in the ball game longer, a laudable goal in these days of record feed prices, volatile milk values and scrimped operating margins. PD

Joel Karlin

Commodity Manager/Market Analyst

Western Milling