In the Supreme Court term which began in October, the court has been called upon to decide what is a religious minister and what is not, whether a GPS monitoring by police is a search or not, and whether the Congress can mandate that individuals buy health insurance or not. In the midst of those weighty decisions, it recently decided what a pig is. This tale begins with a cow. Early in 2008, undercover photographers for the Humane Society of the United States caught workers at a California slaughterhouse mistreating a non-ambulatory cow. It was shocking footage.

No matter whether it represented one event in ten million or was generally descriptive, the video went viral and, for most of those who viewed it, it was the first and only image they had of a slaughterhouse, and it was not a pretty one.

Following the age-old there-ought-to-be-a-law rule, Congress passed legislation intended to eliminate this abuse. It amended the Federal Meat Inspection Act (FMIA) to specifically address non-ambulatory animals, downers to us. The FMIA had been in effect since Congress passed legislation in response to Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle. The scheme was straightforward.

Animals coming to a slaughterhouse are placed in one of three categories by federal meat inspectors – U.S. approved, U.S. condemned and U.S. suspect. Condemned animals are those which are dead or diseased upon arrival. Suspect animals are primarily downers either on arrival or before slaughter.

The FMIA directed the Secretary of Agriculture to issue regulations for the handling of the suspect animals. The FSIS issued regulations and required that suspect animals be humanely treated, handled in a non-cruel manner and placed under cover. Suspect animals were to be slaughtered separately from the approved animals.

If the meat passed inspection, it could be sold – otherwise it was to be destroyed. That statute is 21 U.S.C. §678 and the regulations are 9 C.F.R. Part 309 (Ante-Mortem Inspection), Part 310 (Post-Mortem Inspection) and Part 311 (Disposal of Diseased or Otherwise Adulterated Carcasses and Parts.)

California was not to be outdone. Its legislature passed a penal downer provision which prohibited slaughterhouses from accepting any downers and, if a downer was delivered or an animal became a downer, it was to be euthanized and the carcass properly disposed of. California Penal Code §599f.

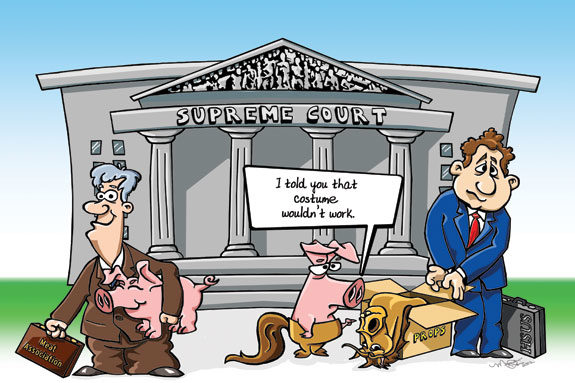

Enter the pig. An association of slaughterhouses, the National Meat Association (NMA), brought suit in federal district court in Sacramento against the State of California and its governor and attorney general, claiming that the federal statute had preeminence over the California statute. The Humane Society moved to intervene as a defendant and the American Meat Institute intervened as a plaintiff.

NMA sought an injunction against the state law, which meant that California should be barred from enforcing this penal provision. The arguments were that, under the U.S. Constitution, the federal law would be the law of the land and if there was a conflict, the federal law trumped the state law.

In this case, NMA argued that FMIA preempted California from enacting legislation regarding how slaughterhouses handled downers at plants within the state. The FMIA specifically stated that the states could not modify federal laws and regulations regarding premises, facilities and operations of a slaughterhouse.

NMA argued that the regulations regarding handling downers was within this “premises, facilities and operations” framework and, as a result, California’s penal code, which made accepting a downer animal as dictated by FMIA a criminal act, should be preempted.

California and HSUS argued that the meat from downers was a different type of meat from non-downers. FMIA and subsequent court decisions has allowed states to regulate the type of animals that could be slaughtered. For example, the courts had upheld against challenges to a Texas law that prohibited the slaughtering of horses. Thus, today it is still illegal for horses to be slaughtered in the state of Texas.

HSUS, using the Texas case as its premise, argued that a non-ambulatory pig was different than an ambulatory pig and that California had essentially defined a new type of animal – a non-ambulatory pig. As such, it had full rights under the U.S. Constitution and FMIA to protect its citizens from having such animals available in the food chain.

In response, Federal Judge O’Neill focused his attention on slaughtering pigs. In obvious common sense, he disagreed with HSUS saying, “A pig is a pig. A pig that is laying down is a pig. A pig with three legs is a pig. A fatigued or diseased pig is a pig.” He held that FMIA preempted Section 599f and issued the injunction – Nat’l Meat Ass’n v. Brown, 2009 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 12523.

Not happy with the result, California and HSUS appealed to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. That court disagreed with the district court and said that non-ambulatory pig meat was a different type from ambulatory pig meat.

Chief Judge Kozinski, in the opinion of that court, quoted Judge O’Neill and called it “Hog wash.” The court of appeals went on to say that California could call meat from a non-ambulatory pig a different type from that of an ambulatory pig and reversed the District Court’s decision – Nat’l Meat Ass’n v. Brown, 599 F.3d 1093, (9th Cir. Cal., 2010).

The NMA and AMI asked the Supreme Court to look at the case. The solicitor general, seeing the prerogative of the federal government at risk, also joined them in seeking review. The Supreme Court does not have to take any case. It gets to choose. Over 10,000 petitions for writ of certiorari, or request to hear a case, are filed with the Supreme Court every year. It accepts less than 100, and this when-is-a-pig-a-pig case was one of them.

The Supreme Court, in a unanimous decision, held that FMIA did preempt the California code and reversed the court of appeals. As a result, slaughterhouses in California could continue to slaughter downers and sell the meat if it passes inspection – Nat’l Meat Ass’n v. Harris.

From the standpoint of a dairyman and other livestock producers, the decision simply means, that based on the statute, otherwise healthy animals can be sold and slaughtered because there is no difference between them and the animals that walked to the killing. What it does not do is prohibit states from passing regulations regarding how animals are treated prior to the slaughterhouse or, for that matter, what animals can be slaughtered.

There was a time when an animal was truly owned by the farmer. He could do as he pleased short of true cruelty. The law was very vague at best. Today most of the population has not even a clue as to what happens on livestock farms.

If they did, some of the practices might shock them even though they are quite reasonable and humane practices. Those who oppose livestock and meat consumption use the isolated excessive cruelty captured in the video to push an agenda that, if fully successful, will end meat production and consumption in the U.S.

In a vacuum of law as to what is and what is not legal, these activists seek to have courts make the law by imposing stricter and stricter standards. In that gap, laws such as FMIA provide protection to slaughterhouses by defining what they can and cannot do rather than let others do so. As an industry, farmers can establish standards on their own.

The National Dairy FARM Program (Farmers Assuring Responsible Management) is one of a number of programs designed to provide the standards which are workable at the farm and responsible to the sensibilities of consumers at the same time.

States such as Ohio have enacted statutes that provide for boards to set standards rather than let them evolve in the courts. By following these standards, farmers are able to avoid starring in the next exposé and protect the industry from overreaching by those who see a different role for meat in our diet and our economy. We should not be hogs and demand more.

Doing the small and necessary things will avoid a wholesale loss of control over our animals. As we all know, pigs get fed and hogs get slaughtered. PD