“You cannot get out of trouble using the same thought process that got you into trouble.” —Albert Einstein Over my 28 years as a hoof trimmer, 23 have been dealing with digital dermatitis and its effects on my clients’ cows. For the international dairy industry, digital dermatitis (DD), more commonly known as strawberry foot, is one of these disease problems that has gone from a nuisance on a few cows in the late 1950s and 1960s to becoming the leading cause of lameness in dairy cattle in the world.

The average cost of DD per cow case is more than $105. However, when I do a farm analysis for a producer and we review the number of cows infected to examine herd costs, nearly all producers say that financial figure is too low. Producers who see the pain the disease causes an animal and its side effects know that the reduced mobility causes reduced dry matter intake that leads to reduced conception rates, etc.

DD is a spirochete of the family Treponemas, which likes moisture, prefers and thrives in anaerobic environments and currently has more than 30 different strains that have geographic identities, the latter of which currently inhibits the economic feasibility for vaccine development. Treponemes hate dry environments and air.

The lesion shown in Figure 1 is a bacteriological reaction to the spirochetes that colonize under the skin. They are capable of entwining around and piercing through the skin cells, causing the pain the animal feels. In a worst-case scenario, they can destroy the pastern of an animal.

This ruins an entire animal, especially first-calf heifers. It generally attacks the rear of the foot between the heel bulbs or interdigital space. It can also form around the dewclaws and even go into the sole of the foot, infecting the corium or quick of the hoof. Researchers now define the organism as an opportunistic disease rather than infectious. It will rarely infect a healthy foot.

DD is easy to kill but extremely hard to get rid of. Why is that? The current explanation for DD affecting cattle in barns is lack of barn hygiene. The dirtier the barn environment, the worse the DD will be. Allowing manure to build up on cows’ feet and legs creates an anaerobic environment, enabling the disease to thrive on an animal.

The solution then becomes incorporating a footbath as a regular regimen, using chemical substances to control DD, increasing alley scraping, more bedding in stalls, etc., in order to control the disease.

However, the truth is, the disease is controlling you.

My clients say, “Well, if it’s my barn, how come only certain cows get infected?” Good question. When I benchmarked my herds in 2010 using computer records, I had a real problem.

How do I tell one client he has the worst cow infection rates (40 percent) for DD in a freestall that scrapes every two hours and another client, who scrapes with a tractor once a day, that he has the lowest rate (11 percent)? Some tiestall barns with immaculate leg hygiene have DD rates more than 20 percent.

What if the problem isn’t so much the environment causing the disease, but rather the animal itself or deeper factors? Here are three factors of successful dairying with unintentional side-effects to consider.

1. Breeding side-effect – feet with narrowed interdigital clefts

After years of seeing many cows never getting the disease, I wondered if it was an immunity factor. But over time and with some inspiration from fellow trimmers, dairy producers and researchers, I developed a hypothesis involving four dairy herds (more than 200 cows, 800 interdigital clefts) to evaluate the width of space in the upper interdigital cleft space (IDCS) of the foot.

I finalized an observational study, backed up with one year of computerized health records, which I presented at the Global Lameness Conference in New Zealand in 2011. This hypothesis shows as the interdigital cleft in Holstein dairy cattle decreases in width, the infection risks of interdigital dermatitis (stable rot) and digital dermatitis (strawberry foot) increases.

Figure 2 is a good visual of what we expect to see. We assume all cows have lots of width above the heel bulbs, allowing air flow.

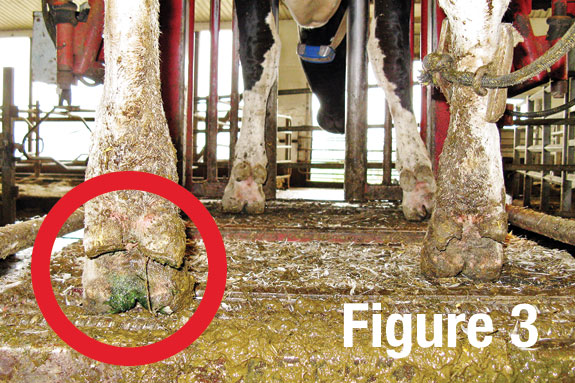

However, the reality is many cattle are more like the one shown in Figure 3, with minimal air space as the cleft is narrowed or closed above and between the heel bulbs.

This means manure can be trapped in the upper IDCS, as well as ammonia.

Those irritations allow the skin resilience of the animal to weaken and fail. This skin failure

allows the treponemes to enter and infect the foot.

The preliminary research for this hypothesis was from a 500-cow dairy herd where I trim. This herd has Holsteins and milking water buffalo.

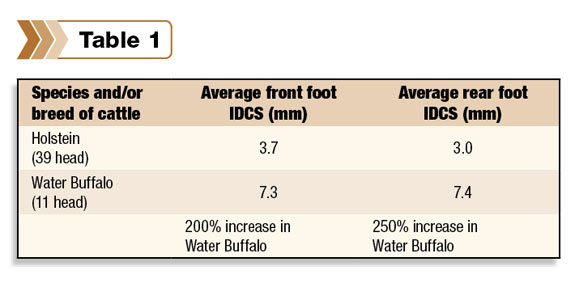

The Holsteins had a high cow infection rate (approximately 30 percent) and the water buffalo had no infection rate after three years. In comparing the two species at the same facilities, Table 1 , shows an interesting result.

The water buffalo have massive interdigital cleft space width in comparison to the Holstein group. In completing the four-herd, 204-head study, the end result was that animals with an IDCS of under 3 mm had a DD frequency rate of 39 percent.

Cattle with an IDCS over 3.81 mm had a 5 percent DD frequency rate. The front feet of the Holsteins hardly ever get DD as they have the superior cleft design and width compared to their back feet.

I use this to explain why some animals are chronically infected – they simply do not have any air space to keep the skin healthy. For breeding purposes, certain sires do show consistent cleft widths.

2. Nutrition side-effect – ammonia

Cattle with high-protein- concentration diets express more nitrogen in their urine than manure. The animal passes the excess through the kidneys in the urine which then evaporates partly into ammonia gas. If the IDCS is not open enough, the ammonia gas gets trapped and weakens the skin in the interdigital space.

Long-term exposure of the cleft skin to ammonia can create irritation and weaken the skin as well. Tiestall cows are very susceptible to this as they are immobile and cannot evade the wetness within the mat or bedding even if they have very clean feet.

3. Hoof trimming side-effect – narrowed clefts

At the International Lameness Conference, the question was posed if how a hoof was trimmed could be influencing the cleft space. This same question was repeated at a speaking engagement earlier this year. I believe it can. The functional or flat method technique’s goal is to reduce ulcers by trimming to flatten and balance heels to prevent ulcers.

Developed by R. Toussaint more than 30 years ago and now a mainstay in many hoof trimming schools, it certainly works for that purpose. However, in recently reviewing the required cut lines to achieve this desired result, the book shows a large reduction in the cleft space.

By adjusting the outer walls of the hoof from an angle of 45 to 70 degrees from the hair line to the floor to Toussaint’s almost-90-degree ideal (viewing from the rear of foot), you can narrow the cleft. In cows with a pre-condition to be narrow in the cleft to start with, this physical lameness prevention can create an anaerobic environment.

In review, if we add Factor 1 (animals with already narrow clefts), combined with Factor 3 (flat and balanced heels), exposed to a level surface, i.e., concrete or pasture mats and then exposed to Factor 2 (ammonia), we have inadvertently created the perfect condition for DD infections. This is my explanation for the variability of infected animals in herds with DD.

We need to remind ourselves that the foot of the bovine has technically not changed over a thousand years. It needs to be flexible in the gait of the animal; it needs air to shed sole and keep skin healthy and it needs a foot designed to allow air to flow between the toes. The foot is designed to walk with flexibility and act as an air pump or bellows to the interdigital cleft, therefore promoting foot health.

The strategy to beat DD is not to just focus on treatment but to also develop strategies to protect and improve skin resilience. Skin resilience is the master key to preventing DD.

We need to examine why there is a deviation in foot structure that influences this variability of openness and determine what can be done to reduce ammonia. The more you can do to keep the skin dry and around good-quality air, which improves skin health, the better your chances are of keeping DD to a minimum.

This could include, for tiestalls:

1. Keep your first-calf heifers’ stalls monitored for wetness. Even if they are clean, use dry lime and/or shavings to absorb ammonia, preventing scalding of the skin of the cleft.

2. If you have a cluster of infections in one area of the barn, check your barn ventilation. Installing one suitable fan can make a difference. My clients with tunnel ventilation have reduced DD rates by more than 50 percent.

3. Get a backpack sprayer and treat DD that way. Make sure you spray the toes in front as well as the heels in back. Frontal spraying allows the treatment to wick down the cleft.

For freestalls:

1. Use a footbath to keep feet cleaner.

2. Protect skin resilience with the use of a footbath.

3. Implement a footbath to eliminate early stages of DD infection.

Consult your veterinarian to see if your footbath solution percentages are accurate. Try to aim for 10-percent-and-under lameness rate from DD. Increase the number of footbaths per week until you reach that goal.

Then reassess to see if you can reduce the footbath use once the infected animals are healed. It is better to footbath proactively more often with lower percentages of chemicals than to require higher reactive rates.

In any situation of lameness the producer needs a dedicated foot health team – the vet, hoof trimmer, feed consultant and foot health product suppliers – to help create careful examinations of factors that allow DD. With a team approach you can develop corrective strategies to maintain and improve skin resilience in your dairy herd’s feet. PD

References omitted due to space but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.