Corn silage is the predominant forage ingredient in many dairies across North America. Producers have moved to heavier corn silage diets for a variety of reasons and benefits (some perceived and some real): Higher tonnage per acre More consistent diet Ability to meet energy requirements more easily Ease of ensiling Good fibre source

The key topic continually raised at meetings and kitchen table discussions is the subject of digestibility. To get a better handle on digestibility, it is important to understand the physical makeup of corn silage.

Corn silage is a large grass species with varying levels of grain corn attached to the stalk. Digestibility of corn silage will revolve around two key areas – the digestibility of the stover (stalk, leaves and cob) and the digestibility of the grain.

Dr. Randy Shaver, University of Wisconsin, would suggest that one-half to three-quarters of the energy in corn silage is derived from the starch in the grain portion. The grain:stover ratio can vary dramatically between seasons and fields and is influenced by growing season, variety and harvesting methods.

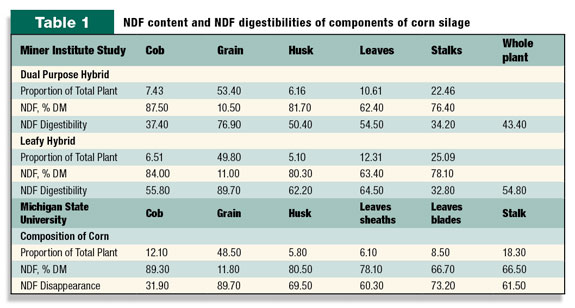

Limited research has been conducted on the composition of the corn plant, but some work has been reported by the Miner Institute and Dr. Mike Allen from Michigan State University. The grain content of the silages in these research studies were high (more than 48 per cent), but this does illustrate the impact of grain content in relation to energy and digestibility.

Starch is more digestible than NDF, which means that grain, at 80 per cent starch, is more digestible than stover and provides more energy, regardless of the digestibility of the stover. Grain is low in NDF (Table 1) , and consequently grain content is inversely related to the NDF or the ADF content of corn silage.

The grain or starch content of corn silage is influenced by maturity, genetics and cutting height. The digestibility of the starch is influenced by maturity, moisture content at ensiling, mechanical processing and time after ensiling.

Two studies from Pioneer Hi-Bred International Inc. demonstrated that as the maturity of the corn silage increased, grain levels increased.

There is a shift from sugar to starch as the plant matures between one-third milk line to black layer. As the amount of grain increases, there will be a dilution of NDF in the plant.

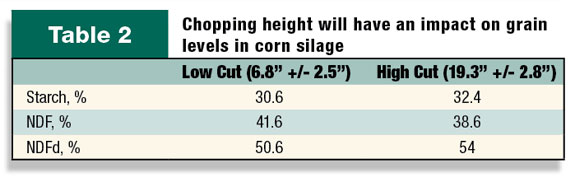

Chopping height (Table 2) will have an impact on grain levels in corn silage. A review of scientific articles and popular press by Wu and Roth on chopping height illustrated some of the key shifts in the analysis of corn silage.

The higher chop height led to an increase in starch (grain) content, a decrease in NDF levels and an increase in NDFd levels.

The digestibility of the grain (starch), although high when compared to the stover, will also be affected by other factors such as:

- Mechanical processing (kernel-processing)

- Storage time

Proper kernel processing is designed to break greater than 70 per cent of the kernels and 100 per cent of the cobs. This generally results in improved ruminal and total tract starch digestion; especially with drier corn silage (more than 40 per cent DM). The improvement in total plant digestibility will be from improved ruminal degradation and decreased due to lower starch passage to the manure.

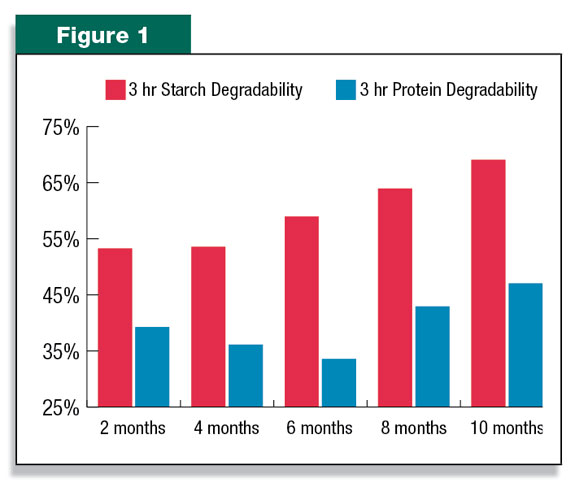

Recent research from Europe has indicated that time after ensiling (storage time) can affect the degradability of the starch in corn silage. The researchers found that both the three-hour starch and protein degradability increased over time. (See Figure 1.)

The three-hour degradability would relate to the “speed” of rumen degradation, while the 24-hour would relate to the “extent” of rumen degradation. These findings have since been confirmed by research in North America.

The researchers also found a significant interaction between the effect of storage time and the DM concentration at ensiling.

The “wetter” corn silage had less of an increase in starch degradability (0.7 per cent increase for silages less than 30 per cent DM) as compared to the “drier” corn silages (25.1 per cent increase for silages more than 37.5 per cent DM).

Stover digestibility

The primary measurement for stover digestibility has been NDF digestibility. This analysis is mainly done through in vitro methods in which NDF digestibility is measured over time.

Dr. Mike Allen has identified large variations in NDFd in vitro measurements between laboratories. This can be due to incubation time (24, 30 or 48 hours), grind size, type of sample and repeatability, but can be accommodated by ensuring that the same laboratory and method is used to compare samples.

Understanding and improving NDF digestibility of corn silage has been a research focus for many seed companies and universities. Research indicates that as NDF digestibility increases in forage, there is an increase in DMI for the dairy cow.

The increase in DMI is the primary driver for the milk production increase that many research trials demonstrate. This response was summarized by Oba and Allen, who indicated that “enhanced forage NDF digestibility increased DMI and milk yield of dairy cows across a wide range of forages reported in the literature.”

From these studies, the authors estimated that a one-unit increase in NDF digestibility (in vitro or in situ) was associated with a 0.168 kilogram increase in DMI and a 0.25 kilogram increase in 4 per cent fat-corrected milk.

A research review by Ev Thomas from the Miner Institute indicated that from the early 1900s to the present, there has been a significant improvement in in vitro total plant digestibility due to the increase in grain content. But the in vitro true digestibility of the stover has not improved on conventional corn silage varieties.

The data indicates there are minimal genetic differences in NDF digestibility between conventional hybrids (4 to 5 percentage units difference). The exception would be low-lignin varieties such as the BMR (brown mid-rib) corn silage.

BMR corn silage will typically be 8 to 10 percentage units higher in NDF digestibility than conventional corn silage. This is primarily due to the lower lignin content of BMR corn silage (1.7 per cent versus 2.5 per cent).

A summary of studies comparing BMR and conventional corn silage show that cows fed BMR corn silage ate an average of 1.54 kilograms more DM and produced 1.58 kilograms more milk.

Dr. Jim Linn from the University of Minnesota states that “the available studies strongly suggest the increased milk production from feeding BMR corn silage is from an increased DM intake and not an increased energy content of the silage.”

Analysis of BMR corn silage and conventional corn silage reveals a similar nutrient content. When 1,350 samples from West New York were analyzed, the starch content followed the same pattern in BMR and conventional varieties.

There were 1,298 conventional samples and 49 BMR samples. Feeding high levels of BMR corn silage could result in high contributions of starch to the diet and must be accounted for in the formulation.

Other factors that will affect NDF digestibility will be related to growing conditions. Research from Dr. Bill Mahanna, Pioneer Hi-Bred, indicates that the weather before and after silking may affect the corn plant height and fiber quality.

Drier weather before silking tends to increase NDF digestibility, while wetter conditions tend to decrease NDF digestibility. After silking, the weather affects the corn grain yield and affects the amount of NDF (grain:stover ratio).

Accumulated growing degree days after silking will have the most impact on affecting corn silage digestibility because of the impact on grain corn yield.

Conclusion

Corn silage digestibility will affect both energy content of the diet and milk production through its effect on energy density and potential changes in DMI.

It is critical to look at total plant digestibility to account for the differences in the grain content and the stover digestibility. PD

References omitted due to space but are available upon request to editor@progressivedairy.com .

-

Bill Woodley

- Shur-Gain Ruminant

- Technical Services Manager, Canada

- Email Bill Woodley