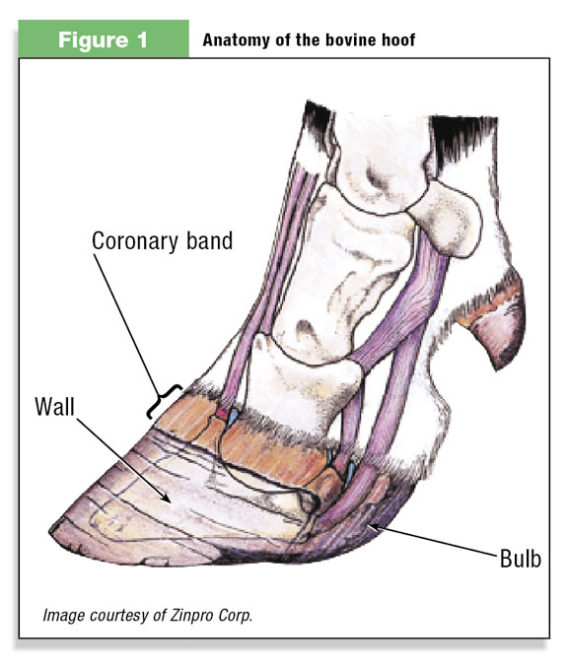

Known as one of the largest health problems on United States dairies, lameness costs producers thousands of dollars each year through veterinary bills, higher culling rates, lost milk production and a decline in reproductive performance. While lameness is not often tied directly to reproductive failure, research continues to show that sore feet are closely tied to breeding pen performance. Lameness 101: Hoof anatomy It’s nearly impossible to understand why the dairy cow’s hoof responds to stress in the ways it does without understanding its structure, which is illustrated in Figure 1.

As you’ll see from the illustration, the bones found in the hoof are suspended by thick layers of cartilage rather than connected directly to the hoof. Without hoof health problems, the bones will remain suspended within the cow’s foot.

When problems arise the cartilage is not able to keep the bone suspended anymore, and the P3 bone in the cow’s foot presses down on the other bones. Foot ulcers are one of the most common results of this pressure.

What’s the cause of lameness?

What makes treating lameness so difficult is that there are many different causes of sore feet. Some of the most common reasons include:

• Standing surface . Confinement on concrete or other hard surfaces increases the effects of excessive load-bearing on cows’ feet. These physical effects are often further complicated because hard flooring surfaces tend to accelerate hoof growth, eventually overloading the claw and causing claw disorders. Confinement on hard surfaces alone can result in lameness; factor in other challenges – including nutrition and environment – and the effects on lameness can be seen more quickly.

• Rumen acidosis . Although few studies established a direct link between rumen acidosis and laminitis, most assume that the feeding program is a major underlying factor.

Acidosis is caused by varying degrees of rumenitis, which encourages the absorption of lactate, endotoxins and bioactive messengers. These, along with many other substances like epinephrine and norepinephrine, cytokines and prostaglandins, are believed to have direct effects on the vascular endothelium of the corium in the hoof.

• Calving . Hormonal changes during the transition period have more recently been linked to lameness. Relaxin is a hormone that relaxes the birthing canal before calving. When released, it relaxes all of the connective tissue in the cow’s body, including that found in the cow’s hoof.

This can cause the P3 bone to sink in the foot, which may explain why the incidence of lameness increases significantly around the time of calving.

• Enzymes . Hoofase is an enzyme that has been identified in pregnant heifers near calving. This enzyme activates other enzymes and processes known to weaken the suspensory apparatus of the hoof bones in first-calf heifers.

• Change in body condition . Cows have a digital cushion in the bottom of each foot that consists of saturated fat in heifers and unsaturated fat in cows. Research shows the size of the cushion and the fat composition is linked to body condition score (BCS). As BCS declines, so does the size and type of fat in the cushion, because the body mobilizes this fat source for other maintenance requirements.

Linking reproduction and lameness

The five identified causes of lameness listed above provide an idea of just how wide-ranging the cause of lameness can be. One of the main effects of lameness is poor performance in the breeding pen, which is further outlined in the research below. The negative effects on reproduction seen in lame cows include:

• Poor signs of heat . Lame cows want to spend as little time on their feet as possible, which means they often can be found lying down. Lame cows may not show signs of heat because they aren’t mounting other cows or standing to be mounted. Furthermore, the stress on metabolic function makes it that much harder for cows to become pregnant.

• Days open . As Figure 2 shows, lame cows are open for a longer period of time than healthy cows. Another study found that cows with sole ulcers were open 63 days longer than healthy cows.

• Days open . As Figure 2 shows, lame cows are open for a longer period of time than healthy cows. Another study found that cows with sole ulcers were open 63 days longer than healthy cows.

Cows with two or more claw disorders were open for an additional 13 days longer for a total of 76 days more than healthy animals.

• Lower conception rate. Lame cows with claw lesions were 0.52 times less likely to conceive than healthy cows. The average time to conception was 40 days longer in lame cows with claw lesions, compared with healthy cows.

Number of breedings per conception was significantly higher when ompared to healthy cows.

• Overall reproductive performance . A trial completed on a 3,000-cow dairy in Florida found lame cows experienced more ovarian cysts and a decline in reproductive statistics, including first-service conception rate and pregnancy rate.

• Increased risk of culling . Cows scored three or greater for lameness were 8.4 times more likely to be culled from the herd compared to cows scoring two or less. They were also more likely to experience increased days to first service, days open and services per conception, which are further outlined in the tables below.

• Economic losses . Just from a reproductive standpoint, the economic losses caused by lameness can provide negative consequences for the dairy. Semen, labor and longer days open all influence herd profitability. That’s what makes hoof health important and maintenance so critical today.

What we can do: moving forward for hoof improvement

With a relationship identified between lameness and reproduction, there are opportunities to make improvements:

• Accept that lameness happens . Before you can treat lameness, you must first accept it as a real and evident problem on dairies today. A British study found that producers estimated only 5.73 percent of their herd was lame, when in reality independent observers identified 22 percent of the cows in the herd were lame. Accepting that lameness may be more prevalent in your herd than you expect is the first step to making changes.

• Set a baseline . A starting point helps move your herd forward and lameness scoring is the best place to start. Score cows in different groups and of different ages to get a sense of lameness throughout the whole herd. Lameness scoring will lay the groundwork for making improvements. Continue to complete routine lameness scoring to identify places for improvement and potential challenges still facing your herd.

• Consult the experts . If hoof health problems are identified, work with the consultants who know your dairy best. Your veterinarian, for example, can help complete lameness scoring and provide a strategy to make improvements. If you think nutrition may be influencing the incidence of lameness, work with your nutritionist to ensure a high level of effective fiber is included in the formulated ration to keep the rumen performing optimally.

• Focus on management . Continue to make improvements to keep cows’ feet healthy, providing plenty of room to lie down and mats in areas where cows are standing for long periods of time. These tools are critical to ensure hoof integrity is maintained.

While hoof health remains an issue on dairies, there are solutions to lessen the effects of the problem. Track cases of lameness and reproduction to see how they influence one another, and how improvements in one area can lead to additional benefits in other dairy management sectors. PD

References omitted due to space but are available upon request to editor@progressivedairy.com.

— Excerpts from Dairy Cattle Reproduction Council Newsletter, Vol. 3, No. 5