A study coordinated by the University of Minnesota, in collaboration with the University of Wisconsin – Madison and North Dakota State University, compared the effects of the functional hoof-trimming method to an adapted version of the technique and found benefits for young cows.

Funding for this study was from the American Association of Bovine Practitioners, Hoof Trimmers Association and the Minnesota Agricultural Experiment Station Population Systems Signature program.

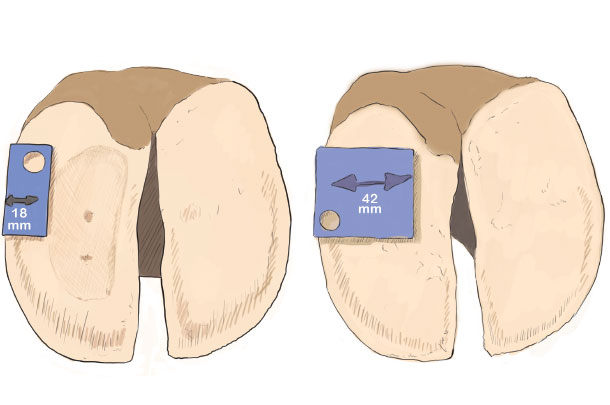

Traditional hoof trimming involves dishing out the weight-bearing claw, known as modeling. Modeling is thought to reduce the occurrence of sole ulcers by reducing pressure on the horn-growing tissue at the sole ulcer location. For this study, two different amounts of modeling were evaluated.

One method modeled the sole ulcer location area up to 42 millimeters from the outside wall of the weight-bearing claw.

The other method increased the modeling to 18 millimeters from the outside wall of the weight-bearing claw. Both methods were examined in a trial involving over 1,500 cows on three Upper Midwest dairies with freestall housing and recycled sand bedding. Approximately half the cows were trimmed with the traditional functional method, and the other half with the more aggressive form.

Two professional hoof trimmers were trained on the trimming techniques and to evaluate the presence of a lesion at 100 to 165 days in milk. Only cows that did not have a hoof horn lesion at their scheduled dry-off trim were enrolled in the study.

Two of the farms were visited every other week for locomotion scoring, and lesion data was collected on all three farms when cows were trimmed again for their regularly scheduled trim between 100 and 165 days in milk.

No differences between the two trimming techniques were found when looking at all of the lesions grouped together or separately for infectious lesions. The study did show a protective effect for hoof horn lesions (ulcers/white line) with the bigger model in first-lactation cows.

That means cows in their first lactation trimmed with the larger model had less risk of developing a hoof horn lesion compared to cows in their first lactation trimmed with the traditional, smaller model. For this group, five fewer cows per 100 developed horn lesions if they were trimmed with the larger model.

Similarly, the effect of the adaptation on time to lameness (as defined by two consecutive locomotion scores greater than 2) was also dependent on lactation number. There was no difference of importance in the risk of lameness for second-lactation-and-greater cows during the observation period. For first-lactation cows, however, the risk of lameness was estimated to be reduced, on average, by 50 percent with a range of 30 to 70 percent.

We also investigated whether there was an effect of the trimming technique on culling risk or milk yield. There was not a difference in the risk of being culled or the milk production between the two modeling techniques. This provides evidence from a culling and milk production perspective that the adapted model is not causing any harmful consequences.

At the farm level, this means modeling the hoof more aggressively reduces the risk of a horn lesion and the risk of lameness in first-lactation cows. It is still unclear why this protective effect was not the same in second-lactation-and-greater cows.

We hypothesize the benefits of using this adaptation in second-lactation-and-greater cows could have been masked by the occurrence of lesions in the previous lactations before enrollment, leading to changes in the bony structures in the foot, a change in trimming technique cannot influence. ![]()

Gerard Cramer is an associate professor, dairy production medicine, with the University of Minnesota. Email Gerard Cramer.

Grant Stoddard is a Ph.D. student at the University of Minnesota. Email Grant Stoddard.