The most exciting new dairy technologies were on display at this year’s Professional Dairy Producers (PDPW) Business Conference in Wisconsin Dells, Wisconsin, March 15-16.

Progressive Dairy hosted these technologies along with PDPW on the Nexus Innovation stage – a live-format presentation that is a cross between a TED Talk and a Shark Tank pitch. Companies with innovations launched in the last year can apply for the award. Winners are selected based on the following criteria: How innovative is the product? How well does it uniquely solve a significant problem for dairies? How much value does this innovation create for dairies?

Here are the five companies selected and recently awarded with a Nexus Innovation Award.

Bacillus strains inhibit pathogen growth in recycled solids for stall bedding

Arm & Hammer Animal and Food Production recently launched a new product to help producers gain more peace of mind about bedding with recycled manure solids. Concerns about increased risk for mastitis cases and higher somatic cell count (SCC) are reasons some producers have not adopted manure solids for bedding. The company’s new award-winning product Certillus Eco Dairy Bedding claims to be able to decrease SCC and mastitis cases for farms bedding with recycled manure solids.

“Our objective was to develop a safe, effective biological application rather than a chemical application for reducing the growth of mastitis-causing pathogens in manure solids,” says Dr. Ben Saylor, dairy technical services manager with Arm & Hammer Animal and Food Production. “We did this by harnessing the power of bacillus.”

The company’s trial data showed farms bedding with manure solids treated with the company’s new product had a year-over-year decrease in SCC count of 57,000 (cells per milliliter) and a reduction in monthly mastitis events (down by nine events per farm on average).

The new product is sprayed onto manure solids in a similar way to how forages are inoculated. The solution is applied after dewatering or drying. The beneficial bacillus organisms begin growing while the recycled manure solids are stacked into a pile, and they remain effective at inhibiting many mastitis pathogens once bedded into stalls. Targeted pathogens include commonly found species of staphylococcus, streptococcus, Klebsiella, E. coli, shigella and other coliforms.

Bacillus are a spore-forming bacteria that produce a variety of antimicrobial compounds. Saylor says that from a library of more than 30,000 unique bacillus strains researchers identified those strains with the genetic ability to produce a diverse portfolio of antimicrobial peptides. The company also collected and analyzed 1,100 different bedding samples from across the U.S. to characterize and quantify mastitis-causing organisms in different bedding types. The highest performing bacillus strains have the ability to produce more than 10 different types of antimicrobials. These antimicrobials work against those mastitis-causing pathogens in dairy bedding. The selected bacillus strains were tested in five Upper Midwest herds (South Dakota, Minnesota and Wisconsin) that were bedding with green or composted manure solids.

“We also were looking for dairies that were removing moisture from their solids with a screw press as this allowed for a single centralized point of product application,” Saylor says. “And we wanted these dairies to be adding fresh bedding into their freestalls multiple times a week into deep beds.”

The estimated return on investment for a 2,000-cow dairy using the product was about $91,000, or an ROI of three to one. That is based on estimating direct treatment costs (diagnostics, therapeutics, the cost of non-salable milk) and indirect costs (future milk production loss, premature culling and future losses of reproduction) for each case of mastitis at $444. The bacillus-based product costs about 4.75 cents per cow per day for a 2,000-cow dairy.

"Recycled manure solids represent a cost-effective and sustainable source of bedding for dairies. But unfortunately, the pathogen levels associated with manure solids and the risk of higher somatic cell count and mastitis, not only challenge current users of manure solids, but they might prevent the future adoption of manure solids by dairy producers," Saylor says.

Saylor says the new product could be used in the future to treat other bedding types besides recycled manure solids.

"This is a brand-new area for our business. We've traditionally been in the feed additive business, but we are expanding our microbial technologies to address issues that producers are facing day in and day out," he says.

Arm & Hammer's new Certillus for dairy bedding is sprayed onto manure solids in a similar way to how forages are inoculated. The solution is applied after dewatering or drying. The beneficial bacillus organisms begin growing while the recycled manure solids are stacked into a pile, and they remain effective at inhibiting many mastitis pathogens once bedded into stalls. Photo courtesy of Arm & Hammer Animal and Food Production.

Wisconsin dairy separates corn stover from ensiled corn silage to increase feed profitability

Dairyman Greg Friendshuh has never been a fan of the Goldilocks diet for his dry cows. He knows dry cows need a low-energy feed source during the dry period, but feeding straw has always been a challenge on his northwestern Wisconsin farm.

"Straw is a lot of work," Friendshuh says. "The semi comes when you're not expecting it, you have to unload it, you have to store it, you have to process it, you have to store it again. If you put a pencil to it like I have, it costs about 30 dollars extra per ton to take straw off a semi and eventually feed it to your cows."

2019 was the year he had had enough of feeding straw to dry cows. That year, wet weather on the Upper Midwest plains where he sources his straw led to feed loads unfit to be fed to his cows.

“When I opened our bales up, they were full of mold,” Friendshuh says.

That is when he started looking for alternatives to straw. He had tried ryelage in the past, but it is another crop to have to grow and put up just right to avoid spoilage. When he penciled his costs to produce it, it was not much cheaper than straw.

That led him to corn stover.

“I asked my nutritionist if we could take the corn stover out of our corn silage and feed it to the dry cows,” Friendshuh recalls. “He said, ‘No one's ever done that before. But if you had the ability to do that, I think it would make great feed.’ So that sent me on my path of trying to figure out how to sort corn silage. And that’s what we’ve done.”

Friendshuh's company Glori Enterprises designed and patented The Fodd. The equipment separates corn stover from corn silage after it has been ensiled in a bunker or pile. Silage starts in a hopper and gets augered into the machine. The silage dumps into a slow-spinning trammel that has 11/16-inch holes. Slowly spinning the silage sorts out the fine material, which falls out below the trammel. The coarse material, or fodder, goes out the back of the machine. The fodder is what now makes up the bulk of Friendshuh's dry cow and youngstock rations. The fodder is replacing hay in the youngstock rations. He says the fodder inclusion is saving him $175 per cow per year.

"The natural attributes of a fodder diet lend toward healthier cows in the transition period. It's palatable, it has the right moisture, the cows don't want to sort it," he says.

Friendshuh has been separating his own silage for the past two years. What he has found is that when the fine and coarse portions of the silage are separated, fine silage moisture increases. Friendshuh says this surprised him at first but makes sense because most of the moisture in the live corn plant is found in the corn and leaves, not the cornstalk. He has also found that the starch levels in the silage fines also increase from 38% to 44%. The total undigestible fiber portion of his milk cow ration has decreased. His dual-purpose silage variety is now feeding like a BMR, he says.

"If you lower undigestible fiber, dry matter intakes are going to go up, and if dry matter intakes go up, milk goes up," Friendshuh says. "Separating corn silage allows a dairy to feed more total corn silage, which reduces feed costs, but it also allows for more milk."

Four pounds more milk is what Friendshuh has recorded on his dairy from the fodder-sorted silage. He has had a few unintentional opportunities to see what happens when he does not feed the sorted silage, and each time, his production drops back down 4 pounds.

Between not having to buy straw for dry cows and increased milk production by the milk cows, Friendshuh says he estimates the dairy nets an additional $300-plus per cow of net profit by using The Fodd to sort silage.

Later this summer, his dairy will receive The Fodd 3.0. This updated unit will be electric-powered versus diesel-powered. Friendshuh found the diesel-powered unit had difficulty starting up at times in the winter.

“I challenged the engineers to build our new unit with 10,000 hours of life, and I wanted it to be as reliable as the agitator on my bulk tank used to be,” he says. “It has a 20-yard hopper. You can fill it up, and it'll take about an hour to run that amount of silage through the machine.”

On Friendshuh’s 1,000-cow dairy, the silage sorter runs for 6.5 hours per day to sort the necessary tons of feed for his rations.

“Year in and year out, whatever corn silage the good Lord gives us in the growing season, we now have a tool that can improve it. We can improve our starch levels. And we can bring down our undigestible fiber. I attribute 4 pounds of my milk to this system.”

Dairyman Greg Friendshuh invented The Fodd to separate out corn stover from ensiled corn silage. Friendshuh has been using the new equipment on his farm for two years and reports more than $300-plus per cow per year in feed savings and increased milk production from the separated silage feed it produces. Photo provided by Greg Friendshuh.

Breakthrough product reinvents old technology to supercharge rumen fiber-digesting bacteria

In 2014, Zinpro began researching a 40-year-old technology that once had a great reputation for performance and reliability but a notorious odor. Through the company's research and eventual break-throughs, the company developed a patented technology to mask the smell, reinventing the product and recently bringing it back to the feed market.

The original technology was developed in the 1980s and marketed under the tagline "more milk, more money." The problem with the product was that it smelled horrible.

"Part of the breakthrough is a better understanding of exactly how IsoFerm works in the rumen and what it's doing to increase milk production with less feed." shares Dr. Dana Tomlinson, global technical services specialist with Zinpro.

"We've actually figured out when the rumen microbiome may be insufficient and needing more of this product," Tomlinson says.

The product - now called IsoFerm - is a combination of branch chain volatile fatty acids. These acids are typically produced in the rumen by the breakdown of rumen-degradable protein.

"What we're providing are carbon skeletons that are identical to the branch chain fatty acids that are needed by the fiber-digesting bacteria in the rumen," Tomlinson explains.

When these branch chain fatty acids are readily available, and not limiting, the fiber-digesting bacteria in the rumen can increase fiber digestion, which increases volatile fatty acid production required for increased milk production. In the 50 herds and over 70,000 cows supplemented during research trials, a nearly 4.5-pound increase in milk production was seen.

Tomlinson says the research shows milk production increases in the same milkfat-protein ratio. This is because both acetate and propionate production levels increase. Thus, milk components are not significantly affected with the addition of the product in the ration. Tomlinson points out this product should be considered an essential nutrient and not a feed additive.

"The cows that are receiving this much-needed nutrient enhance fiberlytic digestion and enhance microbial protein production and increase VFA production," he says. "They respond with increased milk production."

Research shows cows consuming the product also eat slightly less (2% less dry matter intake per cow). Yet contrary to conventional wisdom, supplemented cows do not continuously lose body condition. That is because the cow is more efficient at partitioning energy from the feed she is already consuming when fed the product. Research shows supplemented cows actually better maintain body condition over the course of lactation.

IsoFerm is most effective when the diet consists of specific levels of crude protein and rumen degradable protein, plus sufficient starch and sugar. The diet must also be sufficient in ammonia nitrogen. "We have a team of experts to help evaluate diets and formulate rations to include it," Tomlinson says.

"Fiber digesters require both branch chain volatile fatty acids and ammonia nitrogen, so you've got to make sure you have either some urea, alfalfa, ryegrass or another source, so that those fiber-digesting bacteria can truly grow to reach their optimal performance," Tomlinson says.

The product's base recommended inclusion rate is 40 grams (0.088 pound) for lactating cows and 20 grams (0.044 pound) for dry cows. Once inclusion begins, it takes 56 days to reach optimal performance on branch chain volatile fatty acid supplementation, Tomlinson says.

"It's key to understand that the adaptation period is absolutely unavoidable," Tomlinson says. "There's a rumen acclimation period that takes two to four weeks. There's a metabolic acclimation that takes anywhere from four to eight weeks."

Because of the acclimation periods, the company recommends keeping animals on the product once supplementation begins to ensure producers are getting maximum benefits of the product during the transition and peak milk phases of production.

"We're not feeding the same cow we had 40 years ago," Tomlinson says. "We can now give you the opportunity to be able to feed your cows with less protein and get more out of the rumen. So there are a lot of positives that this product brings to help you be more sustainable."

Zinpro's Dana Tomlinson explains the company's breakthrough product IsoFerm and how its supplemental volatile fatty acids are a necessary nutrient for fiber-digesting rumen microbes. Courtesy photo.

New milk meter communicates without wires, doesn’t need them for power either

A new milk meter that does not require any wires to operate or to communicate the milk weights it gathers is the latest innovation from two-time Nexus Innovation Award winner Nedap.

"The parlor is the heartbeat of the farm. That's where everything happens. That's where the money is made. So why are we not as accurate as possible in that facility?" says Matt Heisner, dairy products specialist for Nedap Livestock Management.

Heisner says the company’s new milk meter is a completely different design than most producers are used to.

“This is not your father's fill-and-dump milk meter,” Heisner says.

The meter works based off a diamond-shaped, plastic-coated float. The float is both the meter's measurement tool and battery power source.

"There are no mechanical or pneumatic moving parts in the meter during milking. There's only a float that floats up in the chamber and then flows back down at the end of milking," Heisner explains.

That float action is the patented way the meter can measure the amount of milk the cow is producing.

One of the design goals for the new meter was to ensure there was no milk flow restriction in the meter during milking. The new meter has an inlet 19 millimeters wide and an outlet the same size. The company claims that the meter can handle up to 22 pounds of milk flow per minute while keeping vacuum levels stable throughout milking.

"There is no space that milk flows through in this meter that is less than 19 millimeters, with no restriction," Heisner says.

The International Committee for Animal Recording (ICAR) has certified the accuracy of data collected from the meter. That certification means the data meets DHIA data standards as well.

Milk production data collected from the meter is stored for a short time during the animal's milking to ensure that any data transmissions issues do not influence an accurate milk weight. Data is transmitted via ultrahigh frequency (UHF). That allows it to avoid interfering with other wireless communications on the farm. The meter is also selfcalibrating. That feature is also ICAR approved.

"A 10 percent deviation in milk measurement is not going to cut it in the margins that we see today," Heisner says. "We need accurate milk data to ensure animals are productive."

The new meter can be installed in line parlors, rotaries or swing-over parlors. A touch-panel display controls each meter for milking operators.

"The touch panel has status indicator lights. It will display milk production numbers. It will display cow ID numbers. You can sort or separate cows after milking. You can start and stop milking. You can do pretty much everything a conventional milk meter interface can do," Heisner says. "It has all the features that a farmer is really looking for."

One of the early adopters of the technology, Austin Webster from Greenleaf, Wisconsin, says he opted for the new meter to be able to watch cow health more carefully.

“My wife mainly looks at the data. She’s our main milker too. When she sees a cow on the computer that shows it has deviated milk by a certain percentage, she's able to watch for that cow to enter the parlor and check her out right away to know what's going on with her. It makes things a lot quicker for treatment,” Webster says.

His equipment dealer also likes that the units are powered without wires. Wires are often the first things to fail in basement parlors, the dealer claims.

"It's proven itself to be accurate at getting cows read, identifying the cows and metering how much milk is in the system. We feel like it's really improved our understanding of our cow health," Webster says. "It's just one of those systems that I feel in this day and age is necessary to have to be competitive."

The Smartflow Milk Meter is the second product in the last three years from Nedap Livestock Management to win a Nexus Innovation Award. Photo courtesy of Nedap.

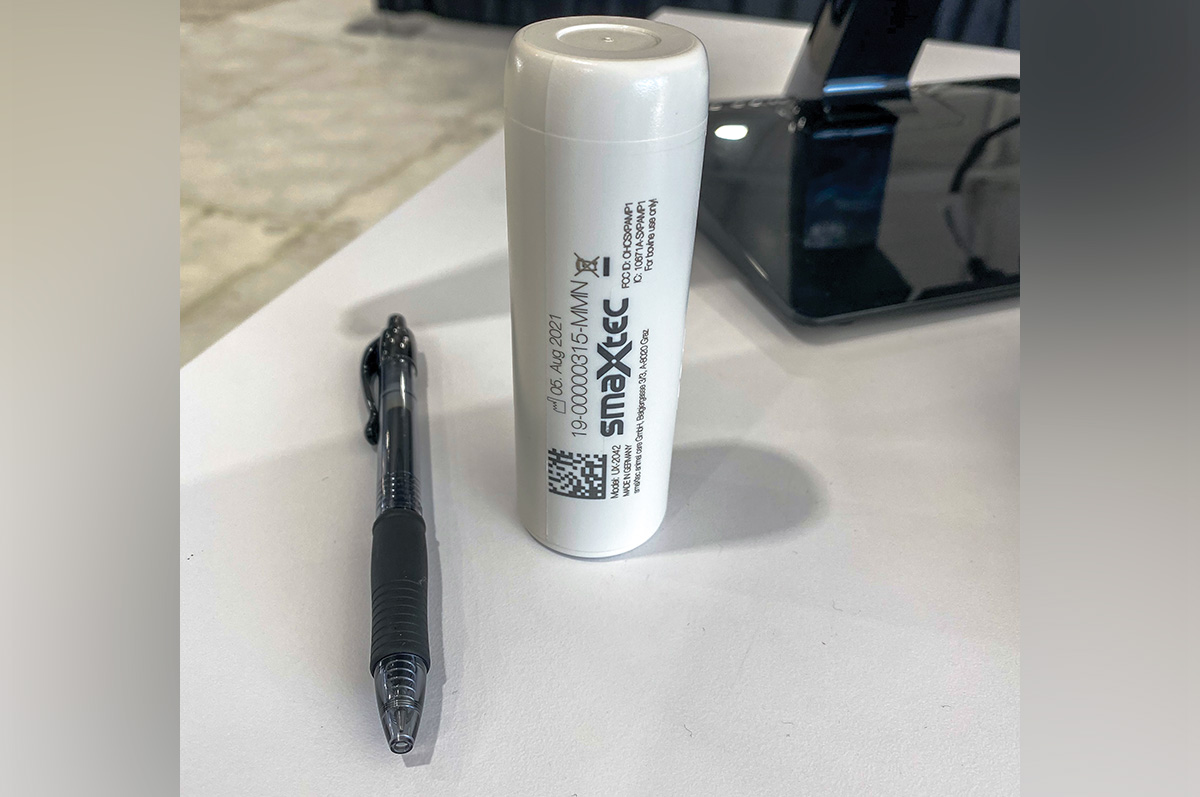

Rumen bolus detects cow drinking levels, aggregates other data for whole health picture

A new feature of an up-and-coming rumen monitoring bolus can now calculate the amount of water a cow drinks, in addition to other health-related activities.

“For the first time in the world, we're able to measure individual cow water intake,” says Liza Gusterer, vice president for smaXtec.

smaXtec recently launched the new feature that calculates the depth of rumen temperature decreases from drinking bouts and based on that data calculates the number of gallons of water a cow drinks in a day. That number can be useful as deviation from normal water consumption can signal the onset of metabolic disorders, the presence of stray voltage or the effects of pecking order issues.

"When we see reduced water intake, this is a sign that we don't have adequate water provision, or that we're beginning to see some kind of disease," Gusterer says. "So the benefits of monitoring each individual cow's drinking behavior is that it's going to be an early indicator for milk production."

The new feature is in addition to the rumen monitoring boluses’ existing capabilities. It can also measure inner body temperature with accuracy of ± 0.018°F, as well as rumination based on rumen contractions, and track activity levels of a cow. Among other functions, the system can suggest an ideal insemination window for cows in heat, signal the onset of calving and catch subclinical signs of disease.

“With inside-the-cow monitoring, we have the ability to detect diseases three to four days before – and often even earlier – than we see them clinically,” Gusterer says.

For example, Gusterer says the bolus has a high degree of accuracy (greater than 90% accurate) at predicting the onset of calving. On average, 15 hours before a cow calves, the bolus detects a cow's natural body temperature drop that is the signal that calving is about to occur. When a cow does not actually calve in that 15-hour window, it is usually a signal that the cow will have a metabolic issue during transition.

"Unnatural temperature decreases are a sign of metabolic disorders," Gusterer explains. "Temperature increases are a sign of inflammation and diseases such as mastitis, metritis, lameness, pneumonia, and it's the first immune system response to something that's going wrong."

Gusterer says the ability to measure inner body temperature combined with activity monitoring and rumination paints a holistic picture of what is happening with a cow. Other methods of body temperature measurement are not near as accurate, she says. For example, rectal temperature monitoring can vary one degree Fahrenheit from a cow's actual temperature. However, rumen temperature monitoring varies only 0.018 degree.

"Measuring temperature from the inside of the cow is going to give us the most accurate measurement possible," Gusterer says. "It's more accurate than anything we've ever been able to do."

Gusterer says producers who first start using the system often fail to respond to temperature alerts once or twice because they are generated three to four days before clinical signs of disease are evident. The adoption of the technology requires a change in management philosophy.

"Producers change from a firefighting approach and having to see their cows be sick before intervention to a preventative approach that trusts the alerts and encourages early intervention," Gusterer says.

Early intervention with nonprescription remedies is one of the biggest benefits of the bolus' use. For example, instead of treating a clinical mastitis cow with prescription drugs, over-the-counter remedies applied earlier are possible. Data from early adopting customers shows a 55% reduction in antibiotic usage for mastitis cases, Gusterer says.

A frequently asked question about the technology is how long does the battery last. Gusterer says the expected battery life is about five years, but the device is guaranteed for the life of the cow.

“Our bolus sits inside of the reticulum of the animal. You apply it once, and you never have to worry about it again. There's no risk of loss, there's no risk of injury to the animal,” Gusterer says.

Data from the bolus is transmitted from inside the cow to a base station. Then the data from the base station is transmitted to the cloud for processing via cellular network. The SIM card inside the base station is programmed to use the strongest cellular signal available to transmit data and is not just limited to one provider. Only a handful of times has the base station had to be hard-wired to be able to transmit data, Gusterer says. Once the data is processed, alerts for cows needing attention will be sent to producers and herdsmen via desktop interface or mobile device.

"You have a clear-cut list when you walk into your dairy in the morning of what needs to be done that day. And the rest of the cows can just be cows," Gusterer says.

The newest feature of SmaXtec's rumen monitoring bolus is the capability to measure the number of drinking bouts per day and estimate the quantity of water a cow consumes. Deviations in these metrics are leading indicators of current or forthcoming challenges for dairy cows, the company says. Photo by Walt Cooley.

Progressive Dairy magazine and Professional Dairy Producers (PDPW) co-sponsor the Nexus Innovation Awards. Applications for the 2024 awards cohort will open in the fall of 2023 and are available for download now on PDPW's website.