Many dairy producers underestimate the effect that heat stress has on cows. While the focus tends to be on reduced milk yield, the systemic effects of heat stress are profound, impacting immune function, reproductive health and even fetal development. This toll ultimately affects the bottom line, potentially for years to come.

In the dairy industry, dry cows experiencing impacts from heat stress incur substantial economic losses exceeding $1.5 billion annually in the U.S. alone. This financial strain is not merely a reflection of lost milk production, which itself amounts to an estimated $810 million annually, but extends to the ripple effects of heat stress on reproductive health and immune function. Heat stress disrupts normal udder development, directly impeding milk production, while also exerting detrimental influences on fetal growth during the final trimester of gestation.

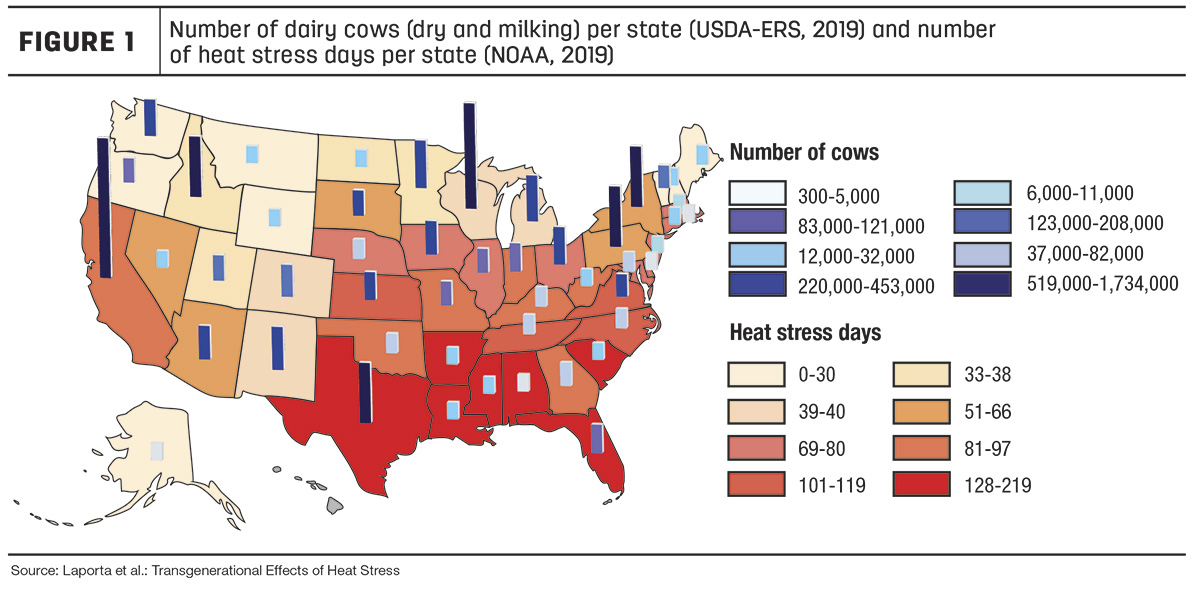

The repercussions of heat stress during the dry period extend far beyond immediate economic losses posing a significant threat to the sustainability of dairy operations (Figure 1). With each instance of impaired fetal growth, the potential future productivity of the herd is compromised, undermining the longevity and resilience of the entire operation. As stewards of these animals and custodians of a vital industry, prioritizing the mitigation of heat stress during the dry period becomes not only an economic imperative but a moral obligation toward ensuring the vitality and sustainability of future generations of dairy cattle.

Effects in utero: Maternal heat stress and offspring viability

During gestation, fetal calves are profoundly affected by maternal heat stress, facing several significant pitfalls in utero that reverberate throughout their lives.

Firstly, maternal heat stress compromises the fetal calf's immune system, making it more challenging for the animal to protect itself for the rest of its life. When a pregnant cow experiences heat stress, it affects the ability of the newborn calf to absorb antibodies from its mother's colostrum or first milk. This compromised start sets the stage for challenges ahead.

When cows experience heat stress, their bodies prioritize self-protection by redirecting energy away from their digestive tract. As a result, fewer nutrients are available to nourish the developing fetus, leading to smaller calves with smaller organs and less functionality. Reduced fetal nutrient supply leads to lower birthweights, a tangible impact for producers (Figure 2). The immunological organs, such as the thymus and spleen, are often impacted and reduced in size, thus resulting in the calf having a weakened ability to protect itself, affecting its immunity from the start. These factors create a vulnerable foundation for the calf's life, making it harder for it to grow up healthy and to handle environmental stressors, particularly heat, later on.

Exposure to heat stress during gestation has lasting effects on the calf's ability to regulate body temperature throughout its entire life. Preprogrammed to struggle with heat, these calves face difficulties upon birth, potentially jeopardizing their survival and future productivity (Figure 3). This susceptibility to heat stress not only results in future challenges but also manifests in weakened immune systems and smaller size at birth. Consequently, these calves face recurrent illnesses and lag behind their peers in growth, incurring higher veterinary and feed costs for producers. Ultimately, farmers are compelled to cull them prematurely due to their diminished potential for productivity, exacerbating financial losses for dairy operations.

Maternal heat stress during gestation imposes a trifecta of challenges on calves, compromising immune function, stunting their growth and impeding their ability to regulate body temperature, ultimately impacting their viability and economic value within the dairy industry.

Caring for youngstock: Investing in future productivity

Youngstock, particularly calves, often receive less attention on dairy farms, with the focus primarily on the lactating cows that generate immediate revenue. It's understandable; after all, calves require constant care and feeding for around 18 months before they start producing milk themselves. However, it's crucial to think beyond short-term gains and consider the long-term profitability of the farm. Mortality rates in pre-weaned dairy heifers are estimated to be between 8% and 11% in the U.S. More than 30% of that loss is because of the failure of passive transfer.

Calves born to heat-stressed cows and fed their mother's colostrum don't absorb antibodies as effectively as calves born to cows that were not heat-stressed and fed their mother's colostrum.

Neglecting calf care now can lead to immune challenges and premature culling down the line, ultimately impacting the farm's bottom line.

Proper investment in calf health and well-being is key to the long game. By prioritizing the nurturing and development of calves, farmers can ensure the calves reach their full genetic potential, contributing significantly to the farm's success in the future. It's about balancing immediate gains with future profitability and recognizing that proper calf care is essential for maximizing overall farm productivity and sustainability.

Solutions for heat stress: Proactive measures for herd health

It’s not all doom and gloom. Combating heat stress just requires proactive measures. Ensuring access to water and implementing effective cooling strategies, such as cross ventilation, are paramount. Managing the feeding and push-up schedule to help encourage smaller, more-frequent meals helps maintain a steady nutrient flow while energy is utilized for evaporative cooling. Additionally, incorporating specific yeast strains like Saccharomyces cerevisiae into dry cow rations and calf starter can help with feeding behavior and deliver a more-consistent flow of nutrients into the gastrointestinal tract, shaping the long-term health and performance of youngstock. Calves could consume that same yeast strain as they transition off milk and continue to be fed through the total mixed ration (TMR) as they are pregnant and entering the milking string.

In conclusion, impacts of heat stress on dairy cows extend far beyond immediate milk production declines with profound implications for overall herd health and farm profitability. Maternal heat stress in utero significantly affects fetal development, leading to compromised growth, immune function and long-term productivity in offspring. These calves often enter the world with lower birthweights and compromised immune systems impacting their immediate health, their future development and milk production. These impacts last for generations, so understanding and mitigating them is crucial for maximizing farm profitability.

References omitted but are available upon request by sending an email to the editor.