I have heard a lot of buzz about utilizing summer annual forages this year as a renovation tool for damaged pastures or as a forage gap-filler in many perennial systems. As I start to think about summer annual forages, there are a few things that come creeping to my mind:

- Will this wet weather be followed by yet another major drought?

- Here comes another season of pest challenges.

Although we don’t have much control over the weather, we at least do have some control when it comes to pests in our summer annual forage crops. In particular, the sugarcane aphid and chinch bug are two pests that really bug me year after year.

Sugarcane aphids

The sugarcane aphid (SCA) has historically targeted sugarcane plants, with reports dating back as far as 1922. However in 2013, reports from Texas and Louisiana indicated the SCA had shifted its preference from sugarcane to any forage in the sorghum family, including grain and forage sorghum, sorghum-sudangrass hybrids, sudangrass and even johnsongrass. The pest rapidly spread east and north since 2013 and can now be found in most states where sorghum species are grown.

The SCA is worthy of being mentioned because of its almost guaranteed yearly appearance, rapid establishment and its potential to damage sorghum crops. Although we have a long way to go in understanding its movement and biology, we do know that the SCA reproduces asexually, resulting in the ability to rapidly colonize sorghum fields. Some reports have indicated that just one aphid has the potential to produce over 75 offspring in as little as 12 days, and therefore warrants weekly scouting before infestation and biweekly scouting after infestation to ensure accurate and timely insecticide applications.

Sugarcane aphids can be easily identified by inspecting the underside of sorghum leaves. They have a soft, white-to-yellowish body with black tips on their feet and antennae. Colonization is highly concentrated around the midvein where they feed by sucking plant sap, resulting in leaf tissue damage and reduced forage and grain yields (Photo 1).

The product of this feeding habit is a shiny, saplike honeydew that covers the ground, stalk and lower leaves of sorghum plants. This honeydew is a good indicator of SCA presence but can also create additional challenges with the grain harvesting process.

The more recent change in plant feeding preference of the SCA has left us with fewer than desired control options. To avoid forage and grain yield losses, it is recommended to treat sorghum crops with a foliar-applied product when 25 percent of pre-boot stage plants are infested or when leaves contain 50 or more aphids per leaf.

Sivanto (flupyradifurone) can be used at a rate of 4 to 7 ounces per acre with a minimum ground application volume of 10 gallons per acre. Up to 28 ounces per acre of Sivanto can be applied annually, with a minimum seven-day retreatment interval. Additionally, Sivanto has a seven-day grazing restriction and a 21-day harvest interval.

Avoid using pyrethroid insecticides in an attempt to control the SCA. Pyrethroids do not control SCA populations and actually do more harm than good by reducing populations of beneficial organisms such as lacewings, lady beetles, syrphid flies and parasitic wasps that are natural predators of the SCA.

A Section 18 emergency-use label has been granted to many Southeastern states in the last few years for use of Transform WG insecticide. Section 18 emergency-use labels are reviewed and renewed on an annual basis and thus far, have not been granted for the 2019 crop year. As we get closer to SCA season, check with your local extension agent for up-to-date information on emergency-use labels.

Chinch bugs

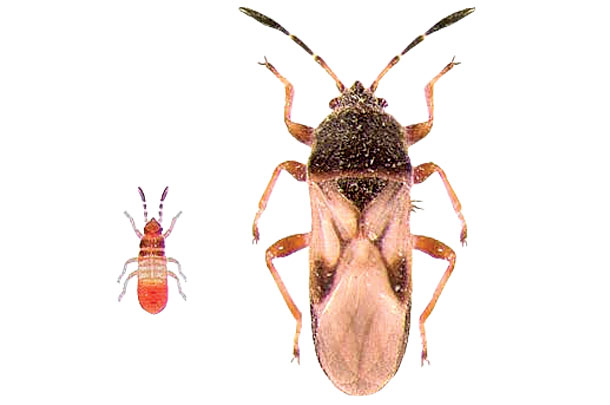

The chinch bug is a common pest of sorghums and other warm-season grasses, but pearl millet is the preferred plant of choice. Chinch bugs have several different life stages ranging from egg to nymph and finally, winged adults. Young, newly hatched chinch bugs are small and bright red in color with a white stripe across their backs. Adults are typically 1/8 to 3/16 inches in length and are almost fully black with the exception of their frosty-white wings (Photo 2).

Chinch bugs are most commonly found in the whorl of the plant or between the leaves and the stem at the base of the plant. They feed by sucking plant juices, which can cause leaf sheath necrosis, yield losses and even tiller death. Chinch bugs are most damaging to small, immature plants, although damage can occur at anytime between seedling and soft-dough stage. If fields have a history of chinch bug infestations, regular scouting should be done by peeling back leaves deep in the canopy and by monitoring the ground around stems where chinch bugs can be easily located after being knocked off by grazing.

Since chinch bugs can be most destructive in young pearl millet stands, beta-cyfluthrin or zeta-cypermethrin can be applied 14 to 21 days after emergence to prevent damage. Since the chemicals must penetrate the canopy in order to be effective, secondary applications should be made after grazing or harvesting and before the canopy has closed. Read the label or ask your local extension agent for grazing and harvesting restrictions.

Seed treatments

Seed treatments can be used to control both the SCA and chinch bugs. Using seed treated with clothianidin, imidacloprid or thiamethoxam at planting can decrease damage. The effectiveness of these seed treatments works well initially but will wear off with time. Therefore, follow up by scouting fields regularly and applying the appropriate foliar treatment. ![]()

PHOTO 1: Sugarcane aphids feed on the underside of a johnsongrass leaf. Photo provided by Deidre Harmon.

PHOTO 2: These are growth stages of chinch bugs. Pictured from left to right are the first nymphal stage and the long-winged adult. Adapted from original photo by David Shetlar, Ohio State University, Bugwood.org.

-

Deidre Harmon

- Extension Assistant Professor and Mountain Livestock Specialist

- North Carolina State University, Department of Animal Science

- Email Deidre Harmon