We are often taught that you have to be able to measure before you can manage. Improving forage utilization requires a bit of management, and thus measurement should come into play.

The notion of measuring forage production seems complicated, but an assessment of available standing forage at a point in time can be obtained through several methods.

Knowing this allows for setting an appropriate stocking rate for the field and controlling the grazing pressure.Perhaps the most straightforward method of assessing the standing forage in a field or range area is the clip-and-weigh technique.

This method is described in the NRCS National Range and Pasture Handbook. The process involves constructing a frame (rectangle, square or circle) of a known size.

This could be constructed from lightweight PVC, cable, rope – or even a hula-hoop can be used. The key is to know the area within the frame. If building a circle, use a length of cable that is 11 feet in length.

This will produce a circle that is about 1.75 feet in radius and 9.6 square feet in area. Alternatively, a square frame that measures 26.3 inches in length and width inside the frame can also be constructed given an area of approximately 4.8 square feet.

There are a few additional items required. A small digital scale to weigh samples will be needed. Several online sites sell quality scales for around $20, or you can obtain a postal scale.

Hand-held spring scales can also be used, but they should be able to accurately weigh in grams in a range of at least 100 grams to 1,000 grams.

A quality set of hand shears for clipping and brown paper bags for collecting the forage is also required. You can use grocery or lunch bags. Other bags can be used as long as they can be weighed on your scales.

Before heading to the field, pre-weigh 20 to 30 bags and write the weights on the bags. Once in the field, randomly toss the frame in an area that is representative of the forage in the field. Next, using your hand shears, clip all the forage to ground level that is inside the frame.

Collect this material and place it in one of the bags. You may need to use more than one bag depending on the amount of forage.

Be sure to label the bags with the number corresponding to the throw (i.e., 1 = first throw, 2 = second throw, etc.). If more than one bag is needed per throw, I suggest using something like 1-1, 1-2 and so forth in which the first number corresponds to your sequence of tosses and the second number the bag.

Bags can be allowed to dry for several days to obtain an air-dry weight or a correction for dry matter is done using published values. Most want a rapid assessment, so a correction factor is used, and this process is described below.

Once the full bag weight is taken, subtract the empty bag weight to arrive at the amount of forage collected. You can average the numbers at this point for all tosses or do each separately.

Next, one needs to arrive at the quantity of forage per acre. Since we don’t often know the percent moisture in the fresh forage, one can assume it is 80 percent, or 20 percent dry matter.

To simplify the math, a couple of correction factors can be used. If you used the dimensions of the circle above, multiply the value by 10 to convert from grams of fresh-cut forage to pounds per acre. If the dimensions for the square above were used, multiply the weight by 20.

Next, correct it to dry matter by multiplying by the percent dry matter, 20 percent or 0.20 in this example.

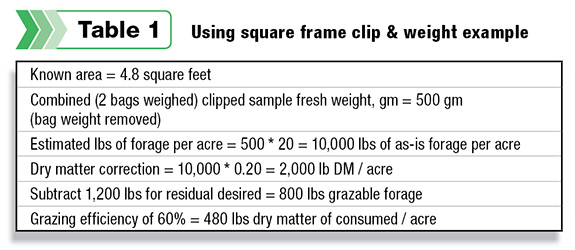

This process estimates the pounds of standing forage available in the field on a dry matter basis (Table 1).

Pasture forage management also ensures that adequate photosynthesis capacity is left behind to allow rapid regrowth.

The amount to leave varies by forage and season, but generally for many cool-season forages leaving 3 to 4 inches of residual is recommended, which is approximately 1,000 to 1,200 pounds of dry matter.

In addition to the residual, some forage will be trampled, refused due to being soiled with urine or feces or be low palatability (i.e., some weeds), and in some fields the terrain is so rough that cattle cannot access the forage.

These factors require making an adjustment to the standing forage available for grazing. The amount of forage that has the potential to be consumed is thus much less than the standing forage measured.

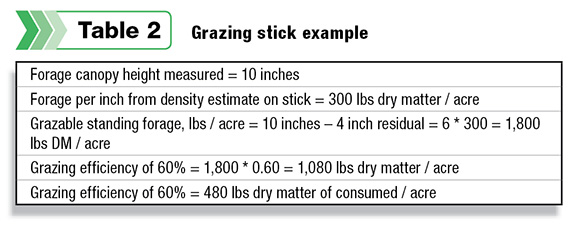

An alternative method to clipping and weighing is using a grazing stick. Grazing sticks utilize the principle of knowing how much forage dry matter there is per inch of forage height. The stick provides a means to obtain an immediate estimate of standing forage and is easy to use.

To use the grazing stick, it is placed on the ground and the height of the forage canopy is measured. When measuring the forage, do not measure the tallest leaves from an individual plant, but rather get a measurement of the canopy or the average height of several leaves and plants.

The density of the stand is then assessed. On many grazing sticks, common forage types are listed along with various estimates of the pounds of dry matter per inch depending on the stand density.

One can then multiply the given value by the measured height to arrive at an estimate of the standing forage available in a pasture. Just as above, a correction for residual and harvest efficiency must be made (Table 2).

Both rising and falling plate meters are additional tools that can be utilized to assess standing forage availability.

They are fundamentally similar to the grazing stick in which the height of the forage is measured. However, rather than using a visual estimate of density, the density is factored into the design.

For a dense stand, the plate is supported more, keeping it higher off the ground under the weight of the plate. The more sparse the stand, the less support the plate is offered and the height will be less.

The plate meters involve clipping and weighing as well. In order to obtain accurate estimates, a series of calibration equations must be developed.

Various equations may be needed for the different forages measured and different times of the year. These equations are derived from using the plate meter to obtain a height value. The forage under the plate is clipped to the ground, dried and weighed.

Several height measurements and clippings are collected. The weights are regressed against the height values to develop the equations.

The rising and falling plate meters are quick and simple to use. But they are only as good as the equations. Commercial rising plate meters can be somewhat expensive in comparison to the other methods.

However, plans for constructing an inexpensive falling plate meter are available from West Virginia University as well as detailed directions for developing equations for its use.

The ability to manage forage for grazing is possible. Learning to measure forage availability and setting stocking rates accordingly will improve forage utilization and productivity. Measure and manage. FG

Jeff Lehmkuhler, PhD

Extension Beef Cattle Specialist

University of Kentucky