These are the most important aspects of any forage. But there is one other intrinsic value worth noting … its nutrient content. In a sense, it is a bale of fertilizer.

Fertilizer is expensive, but worth it

On most farms, fertilizer accounts for the single-largest input into any hay or forage crop. It is a cost of doing business.

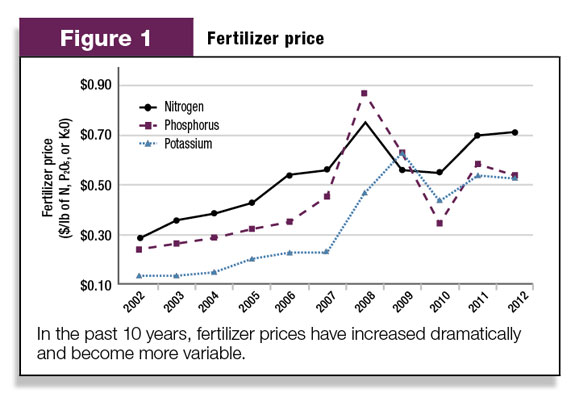

Yes, fertilizer prices remain at very high levels (Figure 1). Unfortunately, there are no substitutes for providing adequate nutrients.

There are no shortcuts. One can try, but it is likely that cutting back on fertilizer will cost more over the long run because of decreased yields and poor stand longevity.

When fertilizer prices increased sharply in 2007-2009, many forage producers substantially cut phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) fertilization rates or left them out altogether.

By the end of 2009, perennial forage stands began to show the effect. Reports of poor yields and severe stand thinning became rampant.

Fertilizer is still a bargain when compared to dragging down yield and the cost of renovating perennial forage stands.

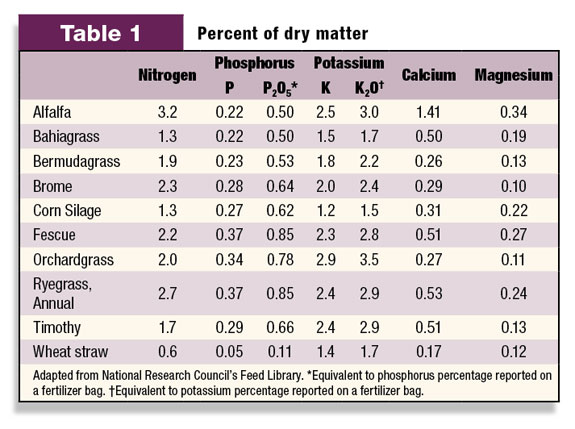

The reason so much fertilizer is necessary is that hay and silage removes large quantities from the soil with each ton that is removed (Table 1).

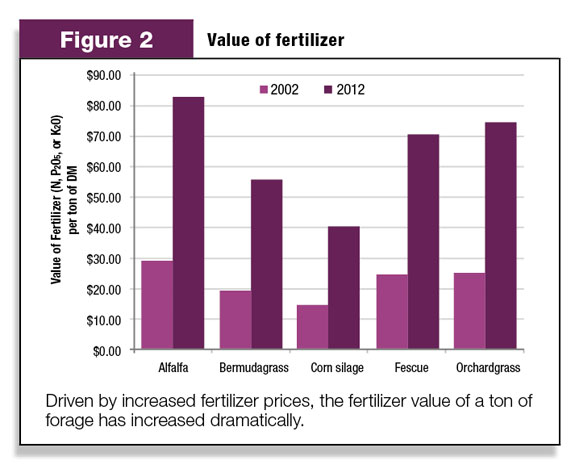

With the run-up in fertilizer prices in the past 10 years, it is important to recognize how the fertilizer value of conserved forage has increased (Figure 2).

Certainly, the total value of the forage is mainly tied to its nutrient value (e.g., digestible energy, protein, etc.).

Nonetheless, one should always understand that the minerals contained in that forage have value, too.

Even forage (e.g., wheat straw) that has little or no nutritive value should never be sold or valued at less than its fertilizer value.

It is critical to capture and reuse

Moreover, steps should be taken to ensure that the fertilizer in that forage is not lost but reused. To understand the urgency of the need to capture and reuse these nutrients, one should understand that the global supply of these nutrients is limited.

To make matters worse, the U.S. has become increasingly dependent upon other countries for our N, P and K fertilizers in a manner similar to our dependence on foreign energy resources.

The best-known example of this problem is the changes that have happened in the past 10-15 years with domestic N fertilizer production (specifically ammonia and urea). As recently as the 1990s, 70 percent of the urea used domestically was produced in the U.S.

At the time, the remaining 30 percent of the urea used in the U.S. came from Canada. Market forces and government policy have altered that paradigm.

There is a direct linkage between the price of N and natural gas prices, the energy source used in the synthesis of nearly all commercial N forms. Seeking efficiency, most of the world’s production of N is now centered in areas where natural gas is abundant and cheap.

Analysts project that in 2012, the U.S. will import approximately 70 percent of the urea that it uses. Our Canadian friends continue to supply us with about 30 percent of the urea used domestically, but a full 50 percent of the urea that is imported comes from the Middle East and another 10 percent comes from Egypt.

Another well-known issue is the world’s dwindling P reserves. Global supplies of readily-available P is known to be only enough to support current demand for a few more decades.

To make matters worse, these P reserves are even less evenly distributed than the world’s oil supply. The U.S. produces 19 percent of the world’s supply of P and is currently the world’s second-largest producer (after China).

However, 65 percent of the P produced in the U.S. comes from a single set of pit mines near Tampa, Florida. Conservative estimates are that this supply will not last more than 30 years.

As a result, we are increasingly dependent upon P from foreign suppliers. A good example is the dominance of Morocco as the major player in the P market. Morocco, which controls nearly 40 percent of global P reserves, is frequently referred to by the rather prescient byname “the Saudi Arabia of phosphorus.”

This is an issue that also influences K projections into the future, but for different reasons. The influence of energy prices on K supplies is much more indirect than with the N supply. Like P sources, K is mined.

Fortunately, the supply of K is known to be enough for at least several more centuries. In fact, expansions in K mining and production are slated for coming years and have many analysts projecting a softening of K prices.

Still, there are risks associated with the world’s K supply. The most worrisome is that K reserves are poorly distributed. The U.S. produces very little K. Much of our domestic use is from supplies in Canada.

But consolidation within the K industry has strengthened the leverage of K suppliers in Russia and Eastern Europe. Under normal and well-governed trade policies, this may not be an issue. But production problems or political crises (e.g., trade disruptions, weakening exchange rates, etc.) could cause abrupt shifts in the balance of K supply and demand.

The point to this discussion is that it has never been more important for hay and forage producers and users to recognize the fertilizer value of the forage they are producing or using.

The fertilizer value establishes the floor value to even the lowest-quality forage. Accounting for these mineral nutrients in a nutrient management plan makes good business sense. Nutrient management planning is no longer just a matter of good stewardship or regulatory compliance.

Well-developed nutrient management plans that identify how to effectively capture the nutrients in waste and efficiently return it to the land can help producers substantially reducer their fertilizer bill, as well as reduce our dependence on (and susceptibility to) foreign suppliers. FG

Dennis Hancock

University of Georgia

Assistant Professor