Shakespeare is probably not often quoted in Progressive Dairy but with a focus of this issue being facilities, it seems appropriate.

Deciding whether to invest in facilities or what kind of investment is one of the more difficult, expensive and long-term decisions a dairy manager will make. These decisions are often made once in a lifetime, and the operation is “stuck” with the results of that decision. So, no pressure.

Major investments often require debt financing. The big elephant in the room is whether returns from the new investment will be enough to cover debt service, asset replacement and a return to management. Is taking on more debt a good or bad management decision?

I’m an agricultural economist, and an economist’s favorite answer to all questions is: It depends. Using debt financing to grow operational capacity is a significant tool in the manager’s toolbox. However, it can also be a major catalyst toward a slide into poor profitability.

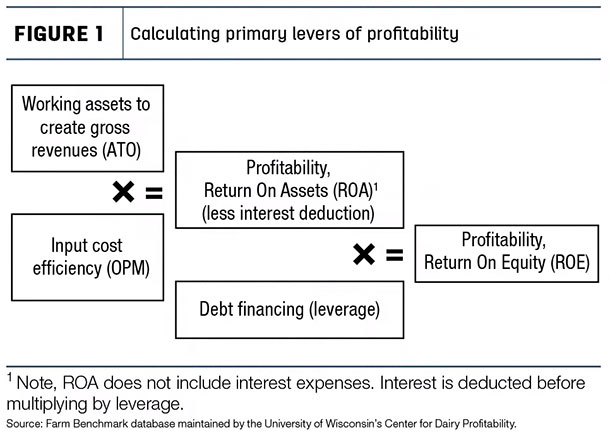

Before going further, let’s consider the three primary levers of profitability (Figure 1), beginning with the first two.

1. Working the assets of the business to create gross revenues to start with (performance in this aspect of management can be measured by the asset turnover ratio [ATO].)

2. Efficient management of inputs such that after expenses are paid there are profits left (measured by the operating profit margin ratio [OPM])

Taken together, these two areas of management provide operational profits, measured by the return on assets (ROA). ROA is a measure of how well management is doing at the business of farming before any distortions created by how much debt one operation has compared to another. Adding the cost of debt will come later.

Much of a producer’s time is devoted to researching ways to either increase the revenue one gets from their assets or how to save on costs. Breeding protocols that increase pregnancy rates or feeding strategies that reduce feed waste are two examples.

Good management resulting in operational profitability is two-thirds of the profit map (Figure 1). The third lever of profitability is leverage.

3. Leverage is using someone else’s money to multiply your operational capacity (measured ultimately by the level and structure of debt financing [Assets ÷ Equity])

Leverage increases the capacity of the operation. For example, if assets are being worked and input costs are being managed well, resulting in $500 of net income per cow, then what happens if I use someone else’s money to improve genetics, create more efficient milking systems or build new facilities that result in increased number of cows, improved production per cow or fewer health problems and less death loss? If, and “if” is the operative word, one can use debt financing to increase the capacity to create additional profits, then the third lever of profitability has added to the bottom line.

Figure 1 shows the math of leverage.

Leverage and ROA are multiplied, resulting in return on equity (ROE), a measure of the profitable return to the owner’s investment. Mathematically, the higher the leverage then when multiplied – the higher the ROE. For this reason, another name for leverage is “equity multiplier.”

However, if one studies Figure 1 for a bit, there may be an awkward revelation. The math seems to show that the more debt I have, then the more leverage I have, and thus the more I can multiply profits. Is that the silver bullet to profitability – more debt?

Like a lot of things in life, don’t forget the fine print. The footnote to Figure 1 shows there is a slippage in the system. The slippage is that interest is deducted from ROA before multiplying times leverage. This deduction is the slippery slope of debt financing and the difference in a wise investment versus an investment that is a drag on profitability. If interest costs are greater than operational profits, then leverage is multiplying a negative number. The multiplier still works; it is just multiplying the wrong way.

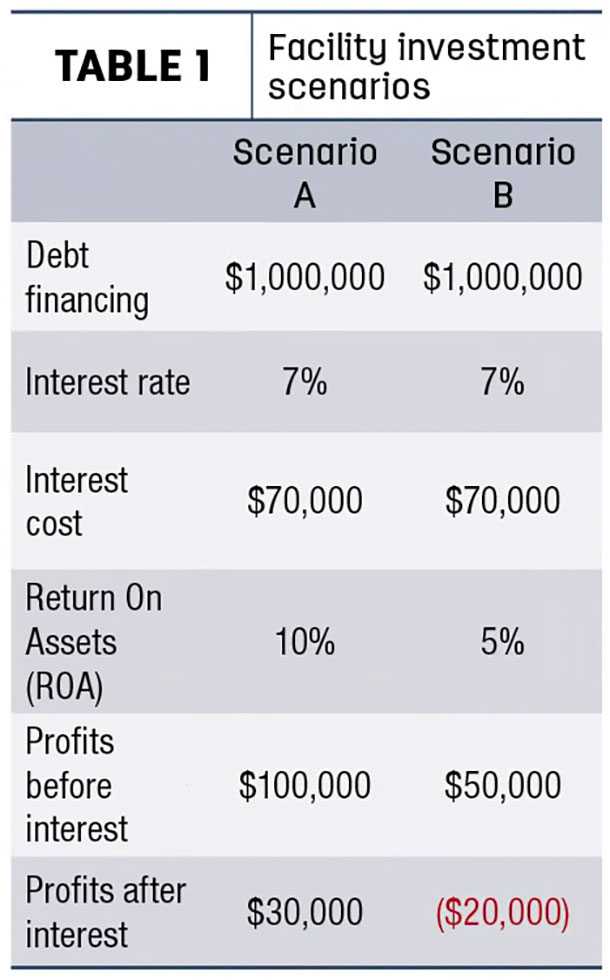

Consider two scenarios, A and B, for investment in a new dairy facility that requires $1 million of debt financing at 7% interest rate (Table 1).

In Scenario A, the new facility enables the improved working of assets and efficiency that results in operational profits of 10% ROA. In Scenario B, the new investment did not have the expected impact, and operational profits were 5% ROA – still positive, just not as good as Scenario A. What is the impact of leverage in these two scenarios? Was the investment in the new facility a good idea?

After the deduction for interest costs in Scenario A, there was $30,000 of additional profits. Someone else’s money was used to enhance profitability; the decision to invest in facilities was wise. In Scenario B, the same leverage was used, but the result was a $20,000 hit on profits after interest was paid. In both cases, leverage is a multiplier; the question is whether it is positive or negative.

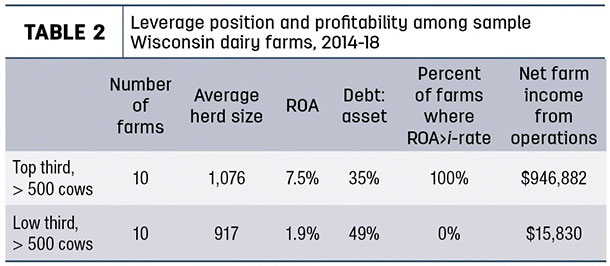

Table 2 shows results from a database of 500-herd-size-and-greater-dairies in Wisconsin.

Each data point is an average of the same farm over five years, 2014-18. Farms were separated into thirds by the level of their average net farm income from operations (far right column). Table 2 shows the top and bottom third.

There are many potential reasons why one farm may be in the top third of profitability and another in the bottom third. However, one of those reasons may be how well they are using debt to leverage greater profits. If the farm is earning more profitable returns from debt-financed capital than it is paying in interest, then the ROA will be greater than the interest rate. As Table 2 shows, 100% of the farms in the top third had a leverage position that boosted their profitability, positive multiplier. On the other hand, 0% of those farms in the bottom third had that situation or, said another way, 100% of low-third farms had interest payments higher than the return they were receiving from debt-financed capital.

So “To be or not to be – an investor” in new facilities is a question of how much interest you will have to pay on any debt financing versus how much return to profits you will get from the new investment. If profits received are greater than the interest rate, then the difference goes in your pocket. If it is the other way, then you must rob equity from somewhere else in the operation to pay the difference.

A few questions for tomorrow morning after breakfast include:

- What will the investment cost (error to the high side)?

- What kind of terms can you get from your bank?

- What is the expected impact on operational profits (the hardest, yet most important to get right)?

- Is management ready for the increased management challenge?

- Has the investment been vetted by your lender, peers, consultants and others?

- Is the investment a step in your long-term strategic plan for the business?