Your cows are converting low-energy diets (compared with diets fed to pigs and chickens) into one of the highest nutritionally-rich human foods: milk. This is like saying that one of us can eat only salads and run a marathon every day for around 300 consecutive days per year. Isn’t that incredible when you think about it?

The reason why cows can do this amazing conversion is because they have a unique “energy plant” powered by a large group of microbes that live in their rumens. The cow provides the microbes with feed, water, buffers, heat, mixing and waste elimination, while the microbes digest the feeds that cannot be digested by the cow itself. Thus, the rumen microbes convert feedstuffs of limited value for other species and humans, such as forages and byproducts, into high-quality nutrients cows can use to produce milk.

The power of the rumen gives dairy producers a lot of flexibility in terms of what sources of energy can be provided to their cows. The rumen microbes can ferment a wide range of carbohydrates including simple sugars contained in molasses and starch in grains, to more complex fiber structures in forages. This flexibility can bring great value to the dairy when a nutritionist looks at the needs of the cow on a nutrients basis and designs rations that will optimize profits by maintaining high levels of production and keeping the rumen and the cow healthy. In other words, dairy cows are “flex-fuel” animals similar to cars with an ability to partially substitute energy sources with minimal effects on performance.

Ok, but what’s the latest?

Recent research conducted at our innovation campus has provided additional evidence of the effects of replacing energy sources. The study looked at feeding two diets varying in starch and digestible neutral detergent fiber (NDF) levels as main sources of energy to 15 first-lactation and 18 multiparous cows. Both diets had the same level of energy, protein and forages (50% of diet dry matter), but the high-starch diet (HS) was 8% units higher in starch (32% versus 24%) and 5% units lower in digestible NDF (14% versus 19%) compared with the high-digestible NDF (HF) diet.

The change in those nutrients was achieved by partially replacing corn grain (23% versus 10%) and corn gluten feed (8% versus 0%) with a mixture of high-fiber byproducts such as soyhulls, wheat middlings and dried distillers grains. Cows were selected to have a wide range of milk production (from 52 to 128 pounds per day) in order to test if the flex-fuel concept could be applied to cows at different production levels.

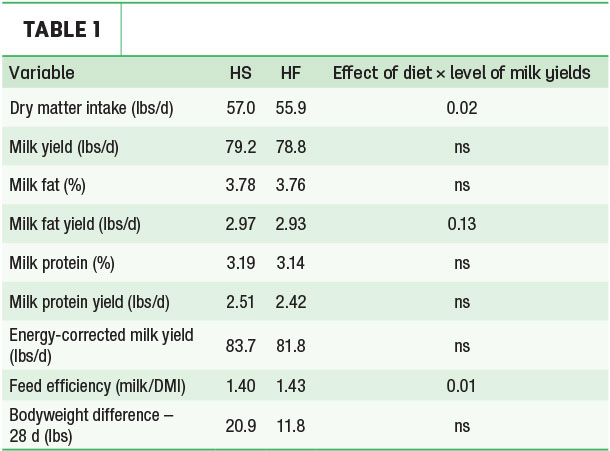

Some of the main results of the study are summarized in Table 1. Overall, milk production and bodyweight change were not affected by diet type.

The HS diet increased intake and decreased feed efficiency in high-producing cows, but not in low producers, indicated by the significant diet by level of production interaction (Table 1). In addition, the HS diet tended to increase milk-fat yield in high-producing but not in low-producing cows. The HS diet increased milk protein yield in all cows except for low-producing first-calf cows and for other responses, lactation number did not impact the results, suggesting that first-lactation cows also can handle changes in energy sources to a certain extent.

Putting into action

This study supports previous published research indicating that, at similar dietary energy levels, diets can be formulated by partially replacing energy sources when it makes economic sense. However, final performance and economical results will depend on the level of production of the cows and the relationship between ingredient and milk components prices. Taking advantage of this flexibility requires accurate lab analyses of available ingredients, sophisticated formulation systems and professional nutritionists.

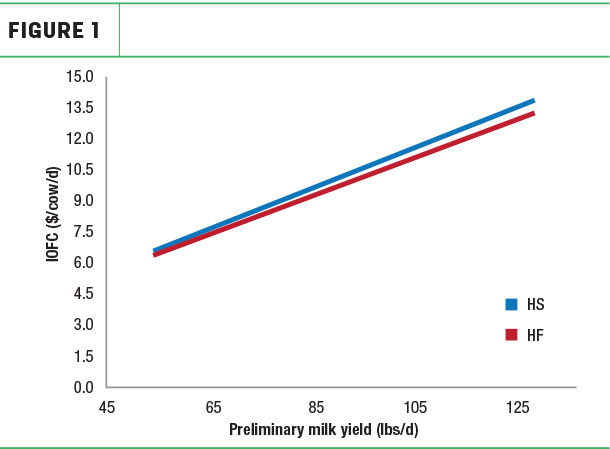

Maximizing the cow’s ability to use a wide range of energy sources can bring considerable improvements in income over feed cost (IOFC) as we can modify the diets to capture favorable ingredients and/or milk components pricing. For instance, under current milk and ingredient prices, the study described above showed that IOFC was similar among diets (Figure 1).

However, due to the interaction observed in milk protein and milk-fat production in high-producing cows, the HS diet could result in higher IOFC under the current conditions. We know IOFC will change significantly if any of these components change, so we should be reviewing and adapting the diet based on those relationships to capture the value of the cow’s flexibility. In addition, because high- and low-producing cows responded slightly differently with these diets, grouping cows by level of production might provide additional flexibility and benefits when formulating diets.

In summary, our current advances in the nutritional knowledge (we know the cows and the ingredients better) and in the formulation tools give us the ability to model different strategies and scenarios to optimize IOFC for each specific condition. In these times when prices are volatile and margins are tight, taking advantage of the flex-fuel capability of your cows is not a theoretical concept for the future; it’s fundamental for today. If you’re not challenging your nutritionist to show you different options, you could be leaving money on the table. ![]()

Paola Piantoni is a senior scientist for Cargill Animal Nutrition, Inc. Email Paola Piantoni.

References omitted but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.

-

Guillermo Schroeder

- Technology Lead

- Cargill Animal Nutrition, Inc.

- Email Guillermo Schroeder