Matt Hersom, associate professor and extension beef cattle specialist with the University of Florida, notes that bull maintenance should start long before a producer is ready to use him.

“Bulls are kind of a forgotten group from a whole-herd standpoint,” Hersom says. “Often, the focus is on the cow herd, or the calves via creep feeding and so forth, or the heifers, especially replacement heifers, [but] we need to work on getting them prepared. If bulls aren’t physically ready [for the breeding season], we have a big problem.”

The worst thing a producer can do is to buy a bull a week before intending to turn him out with the females. Bulls should be purchased in enough time that they can be brought home and acclimated to the nutritional environment of your respective program.

“Nobody wants a thin-looking bull, and most bulls bought at sales have been experiencing a high plane of nutrition,” Hersom sums. “Getting them back to the ranch and getting them back to a high-roughage, high-forage diet and maybe some moderate to minimal supplementation like he’ll be facing when he goes out with the cows – essentially getting him let down from that high plane of nutrition – is a key component."

"If you put him out as soon as you bring him home, the transition is going to be tougher on him and on the producer.”

Ideally, the longer bulls are given to transition and acclimate to the conditions in which they will be working, the better. Giving bulls a 45- to 90-day window is optimal, which allows the animals enough time to slowly transition their diet and gain some physical condition suitable for the terrain if necessary.

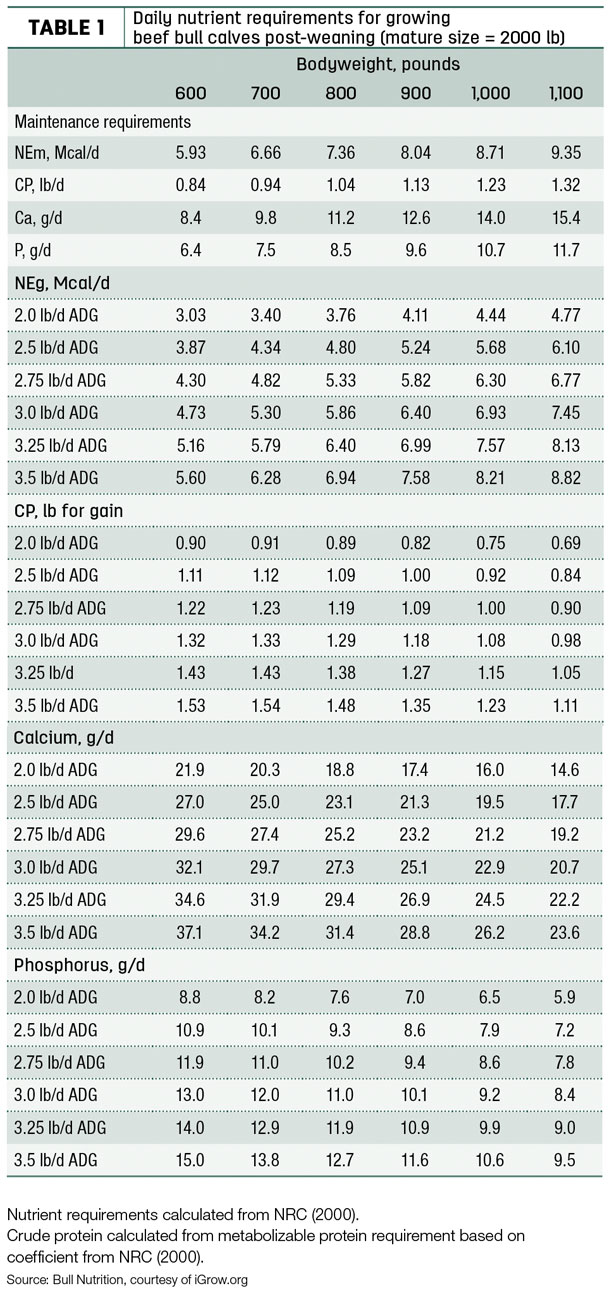

Hersom also notes that getting bulls ready for the breeding season starts with considering any nutritional insults a bull might’ve faced in the off season. These nutritional insults can adversely affect semen quality. Spermatogenesis is roughly a 61-day process, and Hersom advises addressing any nutritional issues at a minimum of 60 days – ideally 90 days – prior to when the bull is needed.

“We need to make sure that the semen he’s got going into the breeding season is as high-quality as we can get, which means making sure he’s had enough energy, making sure he’s had enough protein, and he’s got a good source of vitamins and minerals in front of him that he is consuming,” Hersom says.

Not only is protein important from a metabolic standpoint in getting bulls to a target body condition score (BCS) prior to the breeding season, it is also important for the physiological development of semen and sperm characteristics.

“Not only is protein important on an overall gross basis, amino acids in those proteins are important in the development of the DNA that is going into the sperm [as well as] other components of the semen,” Hersom says.

In addition to protein, zinc has a long-standing reputation as the key mineral when considering fertility in bulls. Trace minerals, Hersom says, are also just as important “because they have key functions that are important in the overall metabolism, health and physiological functions of the bull that enable him to do his job.”

Optimal condition before and during the breeding season

Physically ready, for a bull, is not a one-size-fits-all formula. Factors such as age, breed, rate of cover and geographic location all play big roles into what physically ready means for a producer’s bull herd. Shooting for a BCS 6 when bulls are turned out on females is still the rule of thumb that producers should aim for, regardless of varying factors.

The breeding season is to bulls what game day is to athletes. Eric Bailey, assistant professor of animal science at West Texas A&M, echoes this with his rule of thumb: Bulls should be fit with a little flesh like a linebacker, not fleshy with a little fitness like linemen.

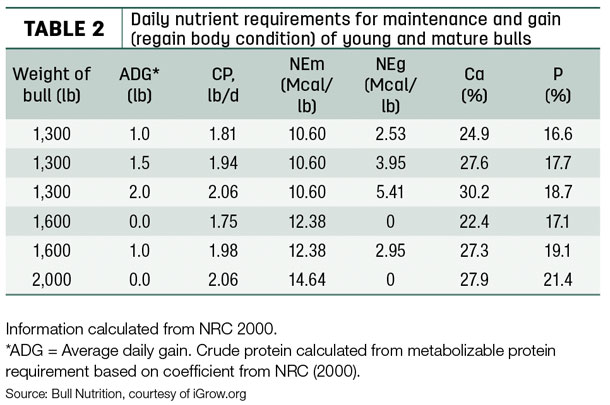

“Optimal condition is a BCS 6 [at the beginning of the season],” Julie Walker, beef specialist with South Dakota State University, says. “We expect them to lose 100 to 200 pounds during that breeding season. It’s a marathon for them.”

Bulls that are higher than a BCS 6 often face decreased fertility and libido due to excess fat on the neck and scrotum. It is ideal to shoot for the BCS 6 going into the season because it is expected that bulls doing their jobs will lose on average 100 to 200 pounds, or 1 to 2 BCS. Once a bull starts hovering around a BCS 4, though, producers should keep an eye on him.

“Hopefully, he is going out at a BCS 5.5 to 6 so that he can mobilize some of that tissue; we have that expectation that he’s going to,” Hersom says. “Once he hits a BCS of 4, though, we need to keep an eye on him. If he gets down to a BCS 3 or lower, he better be at the end of the season because, at that point, he’s pretty much out of mobilizable tissue. He can still mobilize, but at this point it becomes a matter of survival.”

At a BCS 3 or lower, energy partitioning drastically shifts from reproductive development and breeding to maintenance of vital organs such as the brain and heart.

“After BCS 3, his serviceable reserves [stored semen] are pretty low,” Hersom notes. “By that time, he’s mobilized all the energy he was going to be able to dedicate to sperm and semen production. If he starts to fall too far in terms of BCS and energy reserve, we’ll start seeing a decrease in libido.”

Turning bulls out and forgetting them is easy to do, but it can be hard to know what is really going on.

“Just like we monitor our cows to make sure our nutritional program is meeting their needs, we’ve got to make sure our bull has got enough reserves to get him through [the breeding season],” Hersom says. “We probably won’t be able to alter his nutrition greatly because his first priority is breeding cows – second is finding something to eat, but if he is falling off too much, we need to make sure we have a back-up plan, which may be pulling him out and putting someone else in.”

Maintaining a BCS 5 to 6 doesn’t directly correlate with successful conception rates, however. Walker often advises producers to pack a picnic every now and again for a date night out in the pastures. The most ideal times to catch bulls in action are during the cooler parts of the day, such as sunset.

“He may look in good condition, he may look like he has not lost a tremendous amount of weight, but that doesn’t mean he’s actually properly mounting and breeding, or that he has the libido to get the job done,” Walker says. “We can do BSEs and so forth, but we still don’t know if they are going to be successful in the actual mating. The only way to know that is to go out and observe them in action.”

If substitutes need to be made, substituting groups within the same age range is more advantageous than just subbing one or two. The social dynamic can quickly get messed up, and a new dominance structure would need to be established rather than focusing on breeding females.

Yearling bulls

Todd Thrift, beef cattle management at the University of Florida, notes that English bulls don’t reach mature size until close to 3 years old, and indicus-influenced bulls are closer to 4 before hitting mature size.

His rule of thumb for using yearling bulls with that maturity time frame in mind? “If I use yearling bulls, they’re never going to look good again until they are 4 to 5 years old,” Thrift says. “He looked good as a yearling bull, and that tells me a lot about what his calves are going to look like, which is my main concern."

"By the time he becomes an older, mature bull, once he’s got his teeth in and got things figured out, he’ll start looking good again, but if you use him hard early on, he’ll look rough for a while.”

In terms of nutrition variations in yearling bulls compared to mature bulls, keep in mind that most all yearlings coming out of a sale will go backward, Thrift says.

“You need to step him down slow, but he still needs grain and to keep growing; he’s got baby teeth and is about to fall in love with cows, but you need to keep him on a positive plane of nutrition to get him off on the right foot,” Thrift summarizes.

Thrift says with yearling bulls, he only puts them out on as many cows as he is months old – and often for shorter durations than he would mature bulls. Shorter durations, such as bringing them in as cleanups in the later part of the breeding season, gives them a little practice without overworking them, which sets them up nicely to perform well as 2-year-olds.

“Take care of the young bulls and don’t expect too much from them,” Bailey says. “They benefit from a shorter breeding season, as they are often eager beavers and will lose more condition than a mature bull.” ![]()

-

Danielle Schlegel

- Freelance Author

- Whitewood, South Dakota

- Email Danielle Schlegel