I am a third-year veterinary student at Purdue University School of Veterinary Medicine, Class of 2013.

In early May I was part of a short-term mission trip sent on behalf of the Christian Veterinary Mission (CVM) Organization to Copan Ruinas, Honduras, in Central America.

The purpose of the trip was to provide much-needed veterinary services to underprivileged farmers and their families where there are no veterinarians to serve them.

CVM seeks to help veterinarians and veterinary students to serve others and live out their Christian faith through their profession.

They seek to change lives and communities by improving the care of livestock and other animals. Every year, thousands of people around the world struggle to survive because they don’t have the right knowledge, skills and resources to care for their animals.

CVM veterinarians live and work alongside these people to encourage them and provide them with not only much-needed veterinary expertise, but also the hope that is only found in Christ.

As friends and encouragers, CVM veterinarians build lasting relationships with individuals and communities, helping them be transformed through Christ’s love. Christian veterinarians also serve through the profession here at home, demonstrating Christ’s love in word and deed.

On this CVM trip, I was accompanied by a gentleman pre-veterinary student, as well as a retired veterinarian, Dr. Allen Pederson, and his daughter.

Dr. Pederson and his family lived in Copan Ruinas, Honduras, for two years prior to this trip and had formed wonderful relationships with the Honduran people and our host organization – Comision de Accion Social Menonita (http://www.casm.hn/english/index.htm ).

This organization promotes the participation of citizens in the civil society by establishing respectful relationships, dialogue and consensus with local governments.

Its work is rooted in Christian fundamentals and ethics and focuses on the human development of the poorest families and communities in Honduras.

We visited four or five village communities within the mountainous terrain of the Honduran countryside, or “El Campo” as it is called by the local Hondurans.

Within the villages there is one lead man who has been trained some by Dr. Pederson to perform some necessary veterinary services.

These men helped to wrangle and restrain animals as well as learn some of the veterinary techniques we use. The Honduran ranchers are true cowboys in so many respects and clearly love what they do.

Many of these men have only a tree, a rope and sheer determination to restrain these animals.

These farms rarely see visitors, especially Americans. This is partially due to the terrain in the countryside being very treacherous, with severely steep hillsides and unpaved roads.

It would take approximately an hour and a half, traveling up 30-degree inclines at extremely low speeds only to find you traveled a few short miles.

However, the Honduran people are very welcoming and always opened their farms and homes to us as we provided our services once we arrived.

As we traveled into the villages, we were often met by local farmers and ranchers who have brought their animals to the road for us to examine them.

Yes, you read that right; the animals just wander the roads or are herded around the few vehicles that actually travel there.

The lead man from the local village was in charge of telling the community when we would be visiting so the animals could be brought out of their mountainous pasture to a “safer” place to process them.

As mentioned earlier, where and how these farmers process their cattle is much different than anyone in America would ever dream of with such large and dangerous animals.

There are no chutes, stanchions or corrals – just a makeshift halter, a tree and a really long way to fall if someone gets kicked.

The services we provided included clostridium vaccinations for calves, Ivermectin deworming injections for cattle and oral drenches for horses. We also gave tick baths to horses with severe infestations. The idea of this is to use medication topically to remove the already embedded ticks.

All vaccinations, medicines and veterinary supplies can be bought locally without a prescription so they are readily available to the people.

However, most do not know what they are or what they are to be used for. This makes it very important for the Honduran farmers to be taught about these products and their purposes.

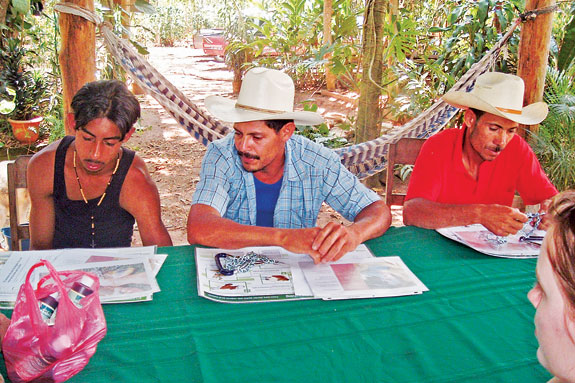

With every trip that Dr. Pederson takes to Honduras, he holds a class for the lead village men. I was asked to discuss a topic of my choice and I chose bovine dystocia, or difficult birthing.

With permission from Progressive Cattleman, I was able to take along copies of its “Steps to safer winter calving” bilingual poster, which was featured in the February 2011 issue.

All aspects of the poster don’t apply to their seasons or production practices, but most of it does and they just gobble up any information that is given to them.

We also distributed a book titled “When There is No Animal Doctor” that was translated in Spanish and they were really excited to receive all of the great information.

The language barrier was difficult to overcome, but the bilingual poster helped immensely. Most of the Honduran people only finish eighth grade in school and rarely have the opportunity to speak any other language other than Spanish.

As I tried to read the poster in my heavily Americanized Spanish, they were able to read and look at the pictures to form ideas and absorb the information.

With little education, the Honduran farmers have become excellent hands-on learners and learn to do things from memory quickly.

I brought and showed them how to use obstetrical chains and gloves, lube and iodine for aseptic technique. They were able to practice some and take these items and ideas back to their communities for future use.

Healthy calving is important on these farms and in these communities, as this is their livelihood. Due to the types of cattle breeds seen, dystocia is not often a problem but it does occur.

The breeds of cattle seen in Honduras usually are a mixture of Jersey and Brahman. I did see some Holstein cows as well. Some farms only had one or two animals – usually a cow and a horse.

Others had nice operations with as many as 20 or 30 head of cattle and abundant grazing pasture. The Honduran people mainly use their cows for food and milk, which they boil and add sugar to before consuming.

I had the chance to enjoy some of their warm milk and it was very good. If they have a larger herd, they may sell one or two at market and make a large enough profit to provide for their families for a long period of time.

They also sell calves to other farmers locally if they are content with their herd and others want to expand theirs.

CVM has been helping this agricultural area of Honduras and across the globe to expand for the last few years by providing veterinary services, training and by forming lasting relationships.

I was blessed with the opportunity to share my veterinary knowledge and calving facts with the Honduran people thanks to the support of my family, friends and Progressive Cattleman.

Even the littlest fact of cattle production that may be common knowledge to most may mean the world to someone who doesn’t know it.

Remember to keep sharing your cattle knowledge with one another and it just may reach the places in this world where it is needed most! ![]()

PHOTOS

PHOTO 1: With little education, Honduran ranchers have become excellent hands-on learners and do many tasks from memory.

PHOTO 2: Honduran ranchers typically only use a tree, a rope and sheer determination to restrain their animals.

PHOTO 3: An overlook of one of the towns in the Honduran countryside.

PHOTO 4: Jessica Lilley, front right, tries to stabilize a cow with a villager to show vaccination protocols.

PHOTO 5: The village of Copan Ruinas in Honduras.

PHOTO 6: Residents of the village gained instruction from Dr. Allen Pederson and his team, and utilized a bilingual centerspread poster from Progressive Cattleman.

PHOTO 7: Cattle in Honduras are typically a mix of Jersey and Brahman, and graze on very steep terrain. Photos courtesy of Jessica Lilley.