One of the biggest mistakes made in designing breeding programs is establishing a goal of producing the largest cows possible, with heavy milk production, when the ranch forage supply can’t support this type of animal.

Severe drought in most of the U.S. during the past two to three years has caused a renewed emphasis on breeding cattle that can economically produce in the ranch environment.

“Beef production is influenced by many components, all of which play a part in determining net return,” Dr. Joe Paschal, livestock specialist with Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service, says.

“These include physical environment, cattle biological type, mating systems, management practices, input costs, prices and market requirements.

While level of production is an important factor affecting profitability, costs of production are equally important.”

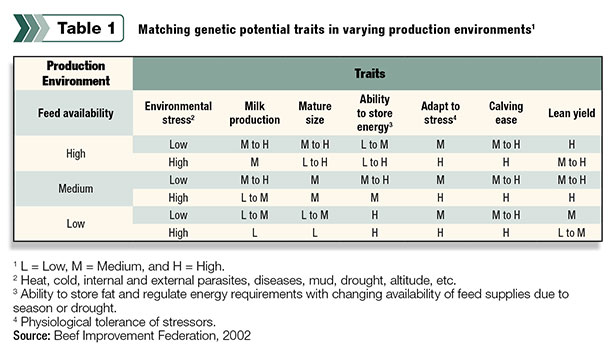

Table 1 characterizes production environments by feed availability and environmental stress. Feed availability refers to quantity, quality and regular availability of grazed or harvested forage and supplemental feed.

Sources of environmental stress include heat, cold, internal and external parasites, diseases, mud, drought and altitude.

Feed availability interactions

Relationships between production environments and recommended levels for the various traits are shown in Table 1.

The better the environment, both in terms of feed availability and lack of stress, the wider the range for optimum milk production. Optimum mature size changes with feed availability and for low and high environmental stress.

“Ability to store energy is important when feed availability is low or inconsistent,” Paschal explains.

“Without this ability, cows are less able to maintain sufficient body condition to re-breed effectively. Cows that are ‘easy keepers’ in low-feed environments may become overly fat and inefficient in high-feed, low-stress environments.

High lean yield and ability to store energy are genetic antagonisms. The optimal level of lean yield will vary with market objectives when feed availability is high.

When feed is limited, however, cows still need to fatten easily, even though this may not be beneficial to their progeny.”

“Levels of cow performance affect feed inputs,” Barbi Riggs of Oregon State University says. “For example, females that are heavy milk producers need more and higher-quality feed than a cow of similar size and moderate milk yield.

Selection of single traits, such as yearling weight and weaning weight, often leads to mature cows too large for some types of grass pasture or environments to support them.

Likewise, selection for high milking ability can lead to a cow whose nutritional requirement for production may not be met by grass production alone.

The result in both cases is a thin cow that does not breed back or a cow that requires supplemental feed.

Genetic selection for desired traits will not only affect cow size, milking ability and calf weaning weights, but also longevity.”

The bigger cows may not always be the money-makers. If a ranch can support 100 head of 1,300-pound cows (130,000 pounds total), then it should also be able to support 120 head of 1,000-pound cows (120,000 pounds total).

At an 85 percent calving rate, the 100 cows will produce 85 calves with average weaning weights of 600 pounds (51,000 total pounds), and the 120 cows will produce 102 calves with average weaning weights of 450 pounds (45,900 total pounds).

The week before this article was written, 600-pound to 700-pound calves sold for an average of $105 per hundredweight (cwt) at the local livestock exchange, and 400-pound to 500-pound calves averaged $188 per cwt.

At these prices, the 85 calves would have sold for a total of $53,550, and the 102 calves would have sold for $86,292.

In this scenario, the smaller cows would have returned $32,742 more revenue than the larger cows ($86,292 - $53,550).

“Regardless of the size of the cows, 44 percent of the approximate $33,000 difference is due to the market,” Paschal says.

“The 85 calves could have been sold at 400 to 500 pounds for $188, totaling $71,910. This action would have reduced the revenue margin between the two groups of cows to $14,382 ($14,382 ÷ $32,742 x 100 = 44 percent added revenue due to market).”

Environmental stress interactions

Parasites and disease are environmental stresses that can be removed by management, but heat, cold, wet conditions, drought and altitude require genetic selections that will allow cattle to cope with these extremes.

When moving cattle to an environment that is very different from the one in which they were raised, losses in production should be expected.

In research studies, calves from cattle moved from the high-altitude, dry and cold environment of Montana to the low-altitude, humid and hot environment in Florida had lower weaning weights than calves from the same closed-genetics group of cows raised in Florida. Similar results occurred with cattle raised in Florida and moved to Montana.

“Consider two production locations in different environments,” Dr. Stephen Hammack, professor and extension beef cattle specialist – emeritus at Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service, says.

“The first is an extensive subtropical rangeland with extreme heat and humidity, distinct wet and dry seasons, and low-quality grazing.

The other is an improved pasture in a climate featuring moderate temperatures, evenly distributed precipitation and unlimited high-quality grazing or harvested forage year-round.

“In the first set of conditions, the applicable genetic type is likely to be relatively small to medium in body size, of lower milking potential with some content of tropical-adapted genetics.

A large, high-milking continental European type would be unsuited to these harsh conditions. But in the more favorable environment, the continental type could be productive and efficient.

A small, low-producing type might not perform well enough to fully exploit the better conditions. However, most beef cows are managed under less-than-ideal circumstances.

These genetic-environmental interactions require intelligent choices of genetic types, not difficult and costly modifications of the environment and management.”

In designing a breeding program, first assess the ranch environment, management systems and markets. Then determine the type of animal required to provide optimum economical production under those conditions. ![]()

Robert Fears is a freelance writer based in Texas.

PHOTOS

PHOTO 1: Rocky ground lowers production in certain genetics because cattle don’t have the feet and legs to handle the environment.

TABLE 1: Relationships between production environments and recommended levels for the various traits.

PHOTO 2: The market should be considered when drafting a breeding plan.

PHOTO 3: Big cattle with high production can thrive on improved pasture.