It is a well-documented fact that mastitis is the most expensive animal health problem in dairy cows and is also the greatest driver of antibiotic use on dairy farms. The number and severity of mastitis events will vary from farm to farm, but all dairies will experience mastitis cases and need to have a management strategy in place to address these challenges.

For many dairies that means focusing on keeping contagious mastitis out of their herd: Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus agalactiae, prototheca and mycoplasma. While each of these pathogens is capable of significant damage to both animal health and milk quality on a herd-wide level, it could be argued that mycoplasma possesses a singular capacity for causing catastrophic herd outbreaks.

Mycoplasma is not a new problem and has plagued dairy farms for over 50 years, so what are the factors that make this disease so dangerous and what have we learned about control and prevention?

Animal health

Mycoplasma is unique among mastitis pathogens, both in its ability to move systemically through the animal and that unlike many bacteria, it lacks a cell wall. This physical characteristic makes it completely unsusceptible to intramammary antibiotics, which are designed to target a cell wall. Some species of mycoplasma may live in other body sites of the cow without presenting any risk to udder health, while other species will find their way to the udder and lead to mastitis.

Mycoplasma mastitis is often characterized by acute, recurring, clinical mastitis events that jump from quarter to quarter; severe drops in milk production and visibly abnormal milk. Death loss from mycoplasma may occur, although this is a rare event. Significant increases to bulk tank somatic cell count (SCC) are often not observed with mycoplasma, due to these cows being removed from the tank for abnormal milk.

Heifers can and will calve in positive for mycoplasma, even in closed herds. If left undetected, these infected animals will be a source of contagious spread to their herdmates. All these factors make mycoplasma a substantial animal health threat and difficult to manage.

Detection

Historically, traditional culture has been considered the gold standard for mycoplasma detection and has served the industry well for many years in decreasing and controlling the number of mycoplasma herd outbreaks. While culture remains a good and economical tool to use for routine udder health monitoring programs, it has noteworthy limitations; mycoplasma are extremely slow-growing bacteria that require special growth conditions and up to a 10-day incubation period.

In recent years, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technology has found its way to the world of milk quality and is capable of rapid detection and identification of five contagious, mastitis-causing species of mycoplasma and one noncontagious species that lives in the reproductive tract and commonly finds its way to the udder (Table 1).

Some progressive laboratories are routinely utilizing PCR tests for confirmation of mycoplasma colonies grown from culture plates or even directly in milk. Because PCR will differentiate strains, we now know that some species of mycoplasma present a serious threat for contagious spread, and some should not cause alarm. The most significant finding is that on some dairy farms, samples become contaminated with a harmless environmental contaminant, acholeplasma, which may cause false positives on conventional culture alone.

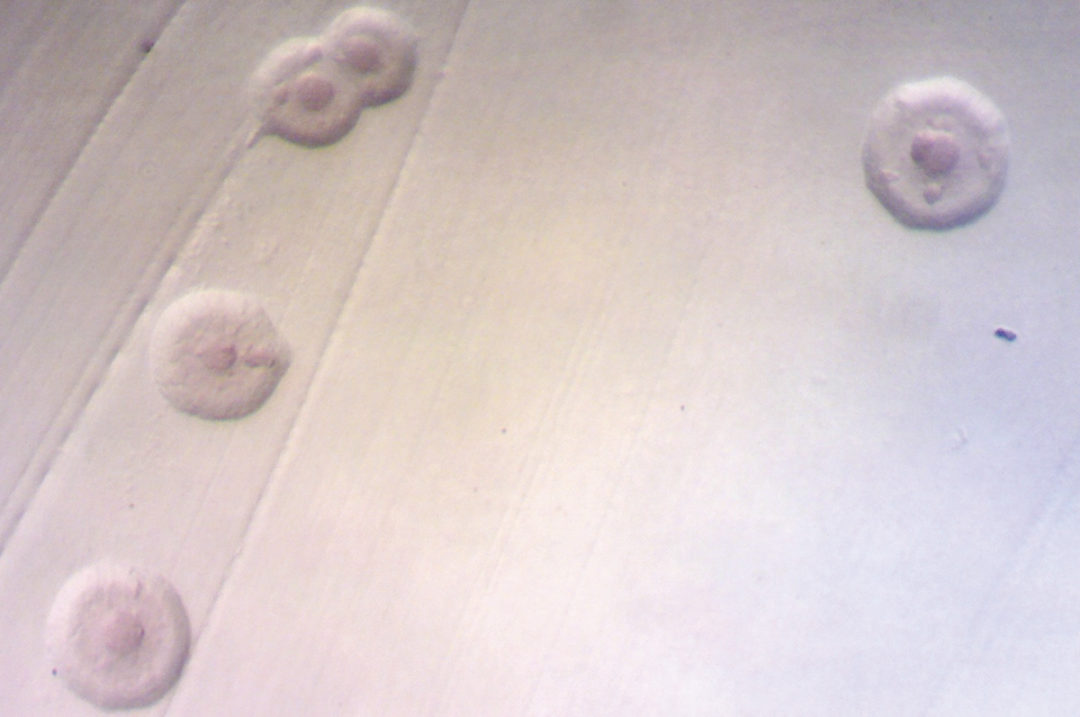

Acholeplasma colonies will look identical to mycoplasma on a culture plate and cannot be differentiated with the naked eye. It is a non-contagious, non-pathogenic bacteria found universally in the cows’ environment and is responsible for approximately 40% of “positive” individual cow cultures (Table 2). This false positivity rate may increase noticeably if samples are taken using poor techniques, resulting in dirty samples. The use of PCR is required as a confirmation step to ensure culture positives are truly pathogenic mycoplasma; laboratories not routinely doing confirmations of colonies may be reporting false positives and inadvertently sending healthy animals to slaughter.

There are numerous laboratories available that offer a confirmation service on bacterial isolates submitted to them, and they may be of assistance to laboratories that do not have PCR capacity. These results can often be obtained within 24 hours of the lab receiving the samples, if running PCR directly on milk. While PCR is often significantly more expensive than culture, the ability for rapid turnaround of results can be critically important in stopping outbreaks and saving animal lives.

Mycoplasma bovigenitalium is a type of mycoplasma that is commonly found in the reproductive tract of cows and can easily contaminate teats during the calving process. This bacterium is not believed to spread contagiously from cow to cow – although contaminated objects may be responsible for spreading it – and will cause individual cases of mastitis. It is present in the bulk tank approximately 20% of the time but will commonly spontaneously disappear without finding individual positive cows. It is important to distinguish M. bovigenitalium from other species, as this species is typically not worth chasing at the bulk tank level.

Transmission and control

In a perfect world, mycoplasma never shows up on the dairy, but alas, we know this isn’t true, and management needs to be prepared with a plan for when it does. The most frequent reasons that mycoplasma does show up are from purchased animals infected with mycoplasma or heifers calving in already positive.

While milking pen transmission absolutely can and does occur, the hospital pen is the place of highest risk for new infections. Mycoplasma infections typically cause a clinical mastitis event, which concentrates these animals in the hospital and results in a dangerous level of exposure to anyone else in there. This may include non-mastitis animals such as fresh or lame cows. Hospital pen transmission can escalate rapidly into a very severe outbreak situation as new infections occur from this exposure and cows are sent back to their milking pens, perpetuating the spread within the herd.

Having a plan already in place for how to deal with the presence of mycoplasma, before it happens, will help mitigate the risk of these potentially catastrophic outbreaks. Where should dairy managers begin?

- Resample the bulk tank – If mycoplasma is detected at the bulk tank level, a second bulk tank sample should be tested as soon as possible. A single infected cow can cause the tank to go positive, and frequently she will either leave the herd soon after or go to the hospital pen.

- Sample every cow standing in the hospital pen – Collecting a second tank sample, while simultaneously sampling every single cow standing in the hospital pen, will help isolate where the problem is or if she has left the herd. Any non-mastitis cows present in the hospital pen need to be sampled as well. Everyone means everyone!

If the bulk tank remains positive after following these steps, the next step in the process is to use an in-line sampler to collect composite pen samples, followed immediately by sampling the individuals in identified positive pens. Cow movement between pens needs to be frozen during this process and remain so until all sampling is complete. The timing of sample collection and speed of results are critical during this “chase” phase of controlling a mycoplasma outbreak; a single uncontrolled cow movement can result in sampling all individuals in a positive pen and finding nothing. In this phase, the use of PCR to get rapid turnaround of results in an outbreak situation is extremely valuable in getting ahead of the herd spread and saving animal lives.

This protocol may need to be repeated several times if the bulk tank is still found to be positive for mycoplasma once results are final. All hospital cows should continue to be sampled weekly, if pen sampling is occurring and mycoplasma is still present on the dairy.

Prevention

Unfortunately, it is not possible to achieve complete assurance that mycoplasma will never appear in the herd. However, there are several actions that producers can take to significantly reduce the risk of an outbreak situation.

- Test all purchased animals – Any purchased animals should be tested and declared negative for mycoplasma, as well as other contagious mastitis pathogens, before they are commingled with the herd. This should be done regardless of any assurance that they have been negative in the past.

- Test all fresh animals – Testing of fresh heifers, whether they are purchased springers or from a closed herd, closes a huge loophole for mycoplasma to enter the herd. One in every 500 heifers calve in positive for mycoplasma. Sampling of animals at freshening is the best way to detect positives early and remove them from the herd before they are a problem. This applies to fresh cows as well. Remember that mycoplasma can move systemically from other body sites, even in closed herds.

- Test all clinical mastitis cases – Because mycoplasma typically results in a clinical event, these cows are our prime suspects, and we want to get an answer on them as soon as possible.

- Monthly bulk tank culture – Monthly monitoring of bulk tank milk is one of the lowest-cost investments managers can make in protecting their herd from contagious mastitis. Combined with a routine cow culture program, this is an excellent early warning system against mycoplasma.

Mycoplasma remains a challenging mastitis problem, even for very experienced dairy managers and consultants. It is unique in numerous ways and has the potential to be incredibly damaging to herd health and ultimately the dairy’s bottom line. As an industry, it is important to recognize and respect the danger of this pathogen and be united in maintaining zero tolerance for mycoplasma on the dairy.