Bill asked if adding amino acids to dry cow rations would be a good idea. His question was interesting, as several factors and new research reports indicate responses to added rumen-protected amino acids may be an economical and effective decision.

Dry cows have an amino acid requirement, not a crude protein requirement. But most nutritionists and dairy farmers target ration crude protein levels at 10 to 11 percent crude protein for mature dry cows, while springing heifer levels are slightly higher at 13 to 14 percent. Several important factors should be considered.

- Dry cow amino acid requirements will depend if the dry cow is in the far-off dry cow phase (the initial 30 to 35 days in the dry period with lower amino acid levels) or close-up dry cow phase (the last 21 days before calving with higher amino acid levels).

Close-up dry cows and heifers will require higher levels of amino acids due to lower dry matter intake, colostrum synthesis and fetal growth demands. The crude protein level is increased 1 to 2 percentage points in the close-up ration above the far-off dry cow ration guidelines listed above.

- The source of amino acids will be from microbial protein synthesis and rumen-undegraded amino acids from feed sources (protein supplements, forages and grain sources) listed in Table 1. These two protein sources added together are called metabolizable protein.

- Dry matter intake is critical to provide the energy needed to optimize amino acids from microbial growth based on digestible organic matter consumed and ration rumen-undegraded protein sources.

- If amino acids are supplemented, they must be rumen-protected from microbial degradation to avoid changing to ammonia and a carbon source for energy.

Low-energy dry cow rations

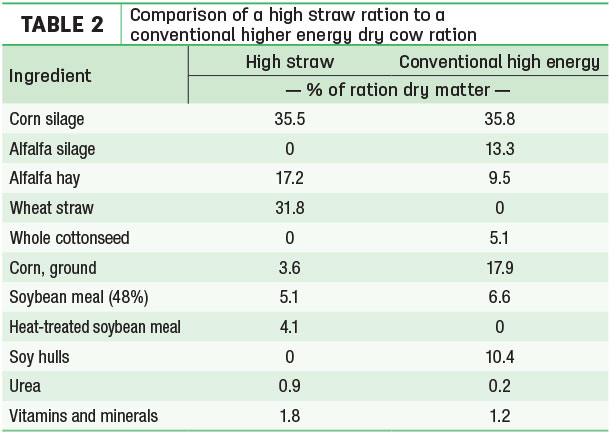

Low-energy dry cow programs to control weight gain, adjust body condition score and minimize metabolic disorders are currently fed to 25 to 35 percent of dry cows in the U.S. These dry cow rations are based on straw or other low-energy grass forage sources (Table 2).

The level of straw varies from 25 to 35 percent of the ration dry matter. Corn silage is the other main forage source that provides energy and starch, which can vary in the level of starch, quality of corn silage and kernel processing.

One key factor for amino acid synthesis by rumen bacteria is the level of rumen-fermentable carbohydrate (starch, sugar and fermentable fiber) needed for optimal energy for microbial growth. Straw is low in rumen-fermentable carbohydrates. Corn silage starch levels and availability are another concern.

The University of Illinois low-energy/high-straw/Goldilocks dry cow ration includes soybean meal (source of amino acids and peptides), heat-treated soybean meal (higher in rumen-undegraded protein as a source of amino acids) and urea (soluble and degraded protein to stimulate microbial growth), as listed in Table 2.

All three nitrogen sources can improve amino acid levels for dry cows. The target level of metabolizable protein is 1,100 grams per dry cow per day. If you are feeding a low-energy dry cow ration, you must have a computer-based ration modeling program that will predict amino acid production from your ration.

Focus on close-up rations

Amino acid levels may be more important in the last 21 days before calving, as amino acid needs are increasing due to lower dry matter intake, higher nutrient demands by the unborn calf (twins would increase this more) and colostrum synthesis (higher in protein and antibody production).

Amino acid demand will be met by the dry cow ration, with the unborn calf requirements receiving first priority, which can also come from tissue/muscle mobilization as a source of amino acids (Table 1) if needed and not provided by the metabolizable protein.

Mobilizing amino acids from dry cow body reserves and lean tissue can lead to additional metabolic problems and health risks. Amino acids can be used as an energy source and have been suggested as a reason to feed higher levels of crude protein to close-up dry cows. But this energy source is more expensive compared to forage and grain energy sources.

The role of methionine in close-up rations

In lactating cows, methionine, lysine and histidine are considered first-limiting amino acids. For dry cows, less research has been reported on first-limiting amino acids. The University of Illinois has conducted several studies based on supplementing rumen-protected methionine.

Methionine roles include more than colostrum milk synthesis and fecal calf growth.

- Methionine has a label methyl group that can produce very low-density protein that moves fat out of the liver, reducing the risk of fatty liver in close-up dry cows.

- Methionine is needed as building blocks for enzyme and hormone formation.

- Rumen-protected methionine-supplemented cows had higher levels of albumin, which can reduce oxidative stress and the negative impact of inflammation.

- Greater levels of carnitine were measured when supplemented with rumen-protected methionine. Carnitine is needed for energy utilization in the animal cell (mitochondria).

- Rumen-protected methionine increased the gene expression for key enzymes in metabolic pathways.

- Greater phagocytic activity by white blood cells has been reported with rumen-protected methionine supplementation, which can enhance immunity and health in close-up cows.

Take-home messages

Evaluating close-up rations for the level of metabolizable protein and grams of amino acids should be conducted. During the transition period, especially in early lactation, dairy cows could mobilize 44 pounds of protein reserves.

Adding 0.1 pound (45 grams) of high-quality blood meal as a source of rumen-undegraded protein lysine or corn byproduct (such as corn gluten meal or corn distillers grain) as a source of rumen-undegraded protein methionine could be considered.

The cost of rumen-protected methionine varies from 2 to 3 cents per gram. Adding 10 grams of rumen-protected methionine can raise close-up rations by 10 percent. If the level of methionine in your close-up ration is marginally low, adding rumen-protected methionine can be fed and evaluated in close-up and fresh cows monitoring their responses. ![]()

-

Mike Hutjens

- Professor of Animal Sciences

- University of Illinois – Urbana

- Email Mike Hutjens