In late October and early November 2016, I led a group from the American Forage and Grassland Council on a tour of New Zealand. The goal for our trip was to foster more of a connection with our colleagues and counterparts while learning more about their livestock industries.

Along the way, we saw a dairy industry that was entering a new era.

The intensification era

Dairying in New Zealand has changed a lot in the last 15 years – and most rapidly in the six years in which I have been a regular visitor. With markets in Southeast Asia (primarily China) demonstrating exponential growth in demand, New Zealand was well positioned to take market share.

With their infrastructure, marketing prowess and relative proximity to these markets, a substantial amount of expansion and intensification occurred in New Zealand.

Since their 2000-2001 season, total dairy production in New Zealand has increased by approximately 70 percent.

Though the number of dairies in New Zealand decreased by 14 percent in this period, they added over 1.5 million cows (43 percent) and 1 million acres (32 percent), and increased their stocking rate by nearly 10 percent.

With land being an uber-limited resource on the New Zealand islands, the country’s land prices are naturally high. But near-irrational exuberance to land capable of dairying reaches $22,000 to $30,000 per acre by some reports. Kiwi dairymen started broadening their horizons.

Some started farms in South America, Southeast Asia and exotic locales like Missouri and Georgia. Others focused on bringing more of New Zealand into production even though it was less suitable to dairying. Many beef and sheep farms on steep hill country were being converted. This included further expansions into the more arid and colder areas of New Zealand’s South Island.

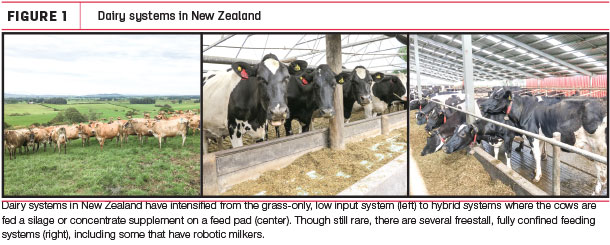

The historical “grass-only” model of milk production has largely gone away (Figure 1).

Now the most common dairy system in New Zealand is a hybrid, pasture-based system that feeds substantial amounts of supplement. Though rare, there are now a few dairies in New Zealand that are housed full time. There are even a number of dairies using robotic milking systems.

Still, most dairy cows in New Zealand will take 60 percent or more of total dry matter intake as grazed pasture. Production is increased with corn silage and bought-in feed. Imports of their national supplement of choice, palm kernel meal, increased from 1.4 million metric tons in 2011 to over 2.4 million metric tons in 2015. All of these changes increased their cost of production.

Historically, New Zealand has seen few rivals to their claim as the least-cost milk producer in the world. Now, their cost of milk production is not too dissimilar to our high-input/high-output dairies in North America. With greater inputs, New Zealand dairy output increased and profitability was high. Then the dairy market pendulum swung back.

The threat of debt

The intensification and expansion on expensive land ran up a mountain of debt on the average Kiwi dairyman’s balance sheet. In June 2016, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand reported that debt in the dairy sector amounted to $40 billion, up from about $30 billion in 2011. Even at low interest rates, debt is hard to service when the dairy is hemorrhaging cash.

With the 2014-2015 and 2015-2016 production seasons being the first two consecutive years of negative cash flow on Kiwi dairies since records began in the 1960s, the New Zealand dairy industry was entering uncharted territory.

Add to this a reported drop in land prices of about 13 percent, and New Zealand’s dairy real estate bubble came perilously close to popping. One can imagine the state of nervousness in bank board rooms and farm family meetings.

Keep in mind, there are no safety nets for dairy farmers in New Zealand. Their government removed all subsidies, tax breaks and price supports in the mid-1980s. Even the extension service was axed. Insurance policies against weather extremes and catastrophes offer some risk management, but disastrous market waves are largely ridden out by dividends from Fonterra or one of the other cooperatives.

Value added to the processed product via dividends paid on their shares gives the Kiwi dairyman a hedge against low milk prices, but that has not been enough.

‘Dirty dairy’

Meanwhile, environmentalists began campaigning against the dairy industry. The expansion of dairying into areas where water resources are limited and slopes are steep gave the environmental community plenty of fodder. News media reports and television ads that link pollution, water shortages and global climate change to the dairy industry are now commonplace in New Zealand.

Often, specific farms are singled out and prosecuted in the court of public opinion, if not the real one. If you are a Kiwi dairy farmer, the overused “dirty dairy” phrase will cause your blood pressure to instantly spike. It is such a common expression among the urban and suburbanite “townies” in New Zealand that it now has its own Wikipedia entry.

Consequently, there is an increasing amount of regulation on water usage, stream protection and nitrate leaching. Regulations on the use of irrigation water and nutrient/sediment loading into freshwater streams are similar to those seen and threatening in the U.S., but New Zealand’s new restrictions on nitrate leaching are a game-changer.

In those regions now implementing the rules, every farm must be analyzed by a computer model that will estimate nitrate leaching.

The computer model, given the rather Orwellian name of “Overseer” long before it was used by regulators, was originally developed for the New Zealand fertilizer industry to help guide fertilization decisions to minimize nitrate leaching loss.

Overseer has since been co-opted by regulators to both assess nitrate leaching rates for each farm and set permissible levels for farms within a watershed. The resultant N caps have effectively capped a farm’s stocking rate and ability to increase productivity per hectare.

Producers were forced to accept these caps in some areas and pay no mind to the fact the model was never fully calibrated, much less designed for this use. Fortunately, the dairy industry has successfully argued for a right to challenge the validity of the data produced by the model.

Dairy New Zealand, the industry-funded organization that conducts research, extension and advocacy in support of the industry, is currently funding several research efforts that evaluate nitrate leaching and strategies to reduce the threat it poses (Figure 2).

The era of uncertainty

Like the U.S. dairy industry, the Kiwis seem to be entering into a new era. One should hesitate at calling it the “post-expansion era,” as there is likely to be some additional expansion. In fact, we observed several new farms coming online when we were there.

It would seem the dairy industry there is poised to enter into an “intensification era,” but this may not happen. Sure, the quagmire that is the current dairy market has slowed some of those steps toward intensification, but environmental regulations appear to be slowing or stopping intensification in New Zealand. One is left to call this the “to be determined era,” as uncertainty is most prevalent. ![]()

-

Dennis Hancock

- Extension Forage Specialist

- University of Georgia

- Email Dennis Hancock