Dairy farmers are often advised by researchers that doing things in a given manner causes a specific result. Whether it’s tilling the soil, feeding the cattle or managing the manure, the way in which things are done can have positive or negative impacts on the surrounding environment.

Mastitis occurs when the environment allows disease-causing microbes to flourish. Runoff of soil and nutrients causes our waterways to degrade, and manure emissions contribute to greenhouse gases and climate change. Altering practices so the impact of agriculture isn’t as detrimental to our ecosystem, and human life can continue to thrive, is a primary focus of researchers today.

But sometimes, those research-generated charts and data just can’t adequately express the complexity and fluidity of living systems. When science is expressed through art, however, it becomes vividly alive.

“Not many things in life are actually fixed, and that flux is what I love about my mud paintings,” says Jenifer Wightman, research specialist at Cornell University and accomplished science-based artist. “Everything about life is a process.”

Wightman is a researcher, working in bioenergy development, sustainable biomass production and greenhouse gas mitigation. She has a master’s degree in environmental toxicology and a bachelor’s degree in cell biology. And she creates visionary artwork based on living systems, simply doing their thing. She’s been creating science-based art for more than a decade.

Manure art

This living art, comprised of organic matter, demonstrates the “fluidity and transformation” of biological systems. Instead of visualizing research results with charts and graphs, which represent data as it was at one moment in time, her art is a living window, showing natural processes as they occur, over time.

“I make art with mud – soil and water. Quite simply, I make clear ‘sculptures’ filled with unique mud samples. Mud is everywhere and selects for a profoundly diverse array of microbes that metabolize all kinds of materials. Manure is just another kind of mud,” Wightman says. “I would love to make some paintings with different kinds of manure. It could be different species of ruminants, grass-fed or grain-fed ruminants, or different manure management systems.”

Wightman’s visions include utilizing mud art to compare the microbial populations that live in different types of manure. Composted versus slurry manure, aerated versus still, milking herd versus heifer: For Wightman, the possibilities are endless.

Sustainability

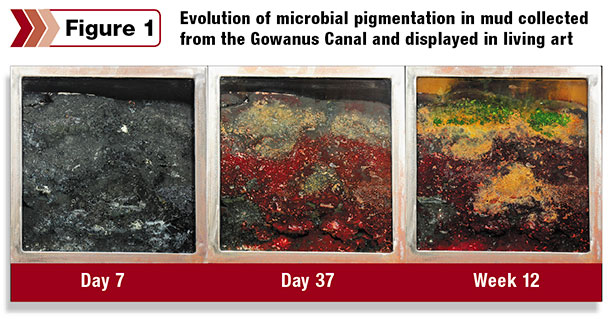

Mud pictures or “sculptures,” alive with microbial life, serve as a way to illustrate the natural world of inherently changing systems. Filled with microbes, the mud sculpture’s ecosystem is constantly altered by them. As one species consumes the supply of nutrients available and excretes their waste products, they are “painting” within the sculpture, causing chemical changes that emerge as pigments.

“Because soil microbes, which usually are buried and not exposed to light, make these pigments in my light-exposed sculptures, the colors allow us to witness the growth and decay of different populations of bacteria over time by watching the transition of color,” Wightman says. “Color acts as an indicator of different cultures. Rise of color tells us a species is thriving; decline of color indicates a species population is declining. A polka dot – such as pink outlining a yellow center – indicates that one species likes the waste product of another species. In this finite world of the mud, there is infinite life.”

As the microbial populations deplete their available resources, they paint their pictures until the altered environment no longer sustains them. But this changed environment provides essential building blocks for some other microbial species.

Wightman’s art provides a perspective on resource use and depletion, and the concept of waste. Sustainability requires that we don’t alter our environment to the degree that it no longer can sustain human life. And waste can become resource if it is managed effectively.

“The only reason we humans are concerned with ‘sustainability’ is that we are now 7 billion humans on a single earth,” she says. “Just 200 years ago, it was less than 1 billion.”

Resourcefulness

With such demand for food and fuel from our limited resources, we’ve utilized science to meet those needs. But doing so has created new problems. Manure, which is a nutrient, has become a waste when concentrated on large farms. Greenhouse gases from fossil fuels accumulate in the atmosphere. Eutrophication of our waterways occurs from excess nitrogen and phosphorous, often from chemical fertilizers used in the production of our food.

“There is nothing intrinsically bad about carbon dioxide, fossil fuels or wanting energy. But when we move great quantities of buried oil to combust into atmospheric gas, it changes the conditions of the world, which requires us to adapt to those changing conditions,” Wightman says. “Scientists will never be out of jobs because the world keeps changing, which changes the variables, which changes the results, requiring a factual claim to be retested.”

Wightman has even used Superfund mud – toxic waste – in some of her work. The toxic properties of the mud didn’t stop bacteria from thriving.

“I was shocked and became profoundly hopeful when I saw the wonderful color patterns. Bacteria saw ‘resource,’ not ‘waste,’” she says.

Living systems change. Human activity does impact our ecosystem, which in turn impacts us. Turning waste into resource is required in order to continue to thrive. If not, just like the microbes in Wightman’s mud art, humanity will alter its environment, succumbing to its own success by depleting the resources needed for continued survival.

“We just have to keep paying attention so we can attend to this miraculous and complicated world,” Wightman says. “Because our earth is one big recycling engine, watching the unfolding process of my mud paintings allows the viewer to witness the process of endless change – or at least that is what I wish.” PD

A portfolio of Jenifer Wightman’s work and more information on her science-based art can be found on her website. She’s also interested in pursuing art with cheese.

Tamara Scully, a freelance writer based in northwestern New Jersey, specializes in agricultural and food system topics.

PHOTO: Artist and research scientist Jenifer Wightman sits upon a two-legged Corten steel public bench she created in a project commissioned for New York City Parks. The bench frames the human industry of the Manhattan skyline and the microbial industry of Randall’s Island Park’s Little Hell Gate Inlet salt marsh. Because bacteria in the artwork can divide every 20 minutes, they also provide an observable model system for us to contemplate how patterns of reproduction, consumption and waste have feedback on the very ecosystem upon which the culture depends. In this pairing of the micro and the macro world, a viewer may rest and contemplate how microbial cultures synthesize and recycle life within a finite ecosystem. Photo provided by Jenifer Wightman.

VIDEO: This time-lapse video features a project from Jeni Wightman of the Gowanus Canal, which is part of a larger project called "Portraits of NYC.” A steel and glass vessel frames mud and water samples taken from the Gowanus Canal and photographed from August to December 2012. Video by Jenifer Wightman.