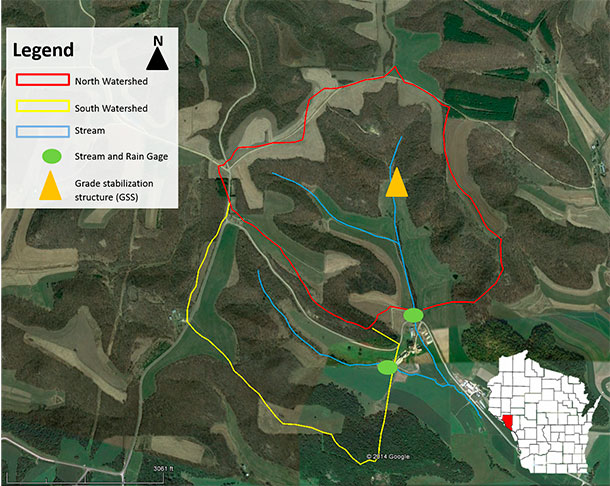

In 2002, Bragger Family Dairy became the first Discovery Farms Core Farm through monitoring efforts on two streams located on the farm. The dairy is located in Buffalo County, Wisconsin, which is known for its steep-sloped, hilled landscape.

Because of the sensitive landscape, the dairy used conservation practices and management strategies to minimize soil loss. The monitoring locations were chosen to compare cropped acres to perennial grassland and woodland. Monitoring took place for seven years. Sites were referred to as the north site (corn and alfalfa rotation next to the stream) and the south site (pasture and woodland with cropped acres further from the stream).

UW Discovery Farms learned valuable lessons from the study on Bragger Family Dairy. Here are the top 10:

1. Agricultural and nonagricultural areas performed similarly while the ground was frozen and after crop canopy was established.

When the soil was frozen, soil and nutrient losses at the two sites were comparable. Runoff at this time of year was driven by snowmelt. This relationship shows that the farming system, including manure management, did not have a significant impact on the stream while the soil was frozen or when snow was melting.

2. Soil and phosphorus were mostly transported in flow during and following storm events, even though most water in the streams comes from springs.

Storm flow accounted for less than 25 percent of the total water flow from the north and south sites, but more than 80 percent of the soil and total phosphorus losses at each site. Storms have the biggest impact on water quality when the soil is not covered by a fully developed crop canopy.

3. May and June were the only months of the year when average monthly P and N loss was higher at the north site compared to the south site.

This was driven by two particular storm events in June 2002 and June 2004, which delivered significant proportions of the soil (55 percent of total) and total phosphorus (44 percent of total) lost during the entire study period.

4. Large storms have a major impact, and it matters what month they occur in.

The two June storms (2002 and 2004) delivered more soil loss than 125 other storm events combined during the entire study period. The large storm events (1 to 2.5 inches of rain per hour) were more impactful in the agricultural watershed due to limited crop canopy in the early June time period. A storm in August 2007 had similar intensity to the June storms but was not even in the top 20 storms for soil loss at the sites. Fully grown crops intercepted rainfall and protected the soil surface, thus preventing runoff.

5. Making sure banks are stabilized and protected from large flow events pays dividends.

Since the monitors at this farm were in the stream, it’s reasonable to think that some of the losses could be coming from the fields and some within the stream. During the large August storm, losses would have likely been much higher if the banks were not stabilized and properly maintained. It’s not just fields or banks to protect, but instead placing a network of practices together to build a resilient farming system.

6. In western Wisconsin, grade stabilization structures are a worthwhile conservation practice to protect streams and fields.

Midway through the study, a grade stabilization structure was installed at the headwaters of the stream in the agricultural watershed to slow water from the wooded areas upstream of the cropland. The structure reduced average sediment concentrations in the stream by 73 percent. This practice is a valuable addition in the driftless landscape to slow water and prevent erosion.

7. Consistent nutrient stewardship practices can decrease nitrogen concentrations in streams.

Most of the nitrogen measured in the stream at Bragger Family Dairy was delivered during baseflow and was in the nitrate form due to the carbonate bedrock that underlays the Buffalo County landscape and springs that feed the perennial streams. There was a downward trend in baseflow concentrations of nitrate at the agricultural watershed site during the study period, and concentrations were nearly identical to those at the nonagricultural watershed (which stayed consistent) by the end of the study. The Braggers are committed to the right rate, time, placement and source of nitrogen, and it is making a water quality difference.

8. Listen to your wife when she says don’t spread manure today; it’s going to rain.

Manure and fertilizer were applied in the monitored areas dozens of times, but only two of the 2,557 monitored days indicated an impact from an application. Manure was applied immediately before a runoff event in October 2005, which increased phosphorus and nitrogen loss. However, it did not impact annual loss significantly and there were no effects on the trout population in the stream. And Joe Bragger’s wife told him not to spread manure that day.

9. Streams were always below the phosphorus criteria for Wisconsin.

Both streams were always below the numeric phosphorus criteria for Wisconsin – an indicator that both were of good quality – and neither was impaired, regardless of land use.

10. Agricultural management and water quality complement each other at Bragger Family Dairy as a result of thoughtful use of conservation practices and nutrient management.

For more information on these lessons learned, click here to read the full project report. Formal printed copies of the report are available upon request. Email a request here. ![]()

Amber Radatz is co-director of UW Discovery Farms. Email Amber Radatz.

PHOTO 1: Monitoring stations were set up in two different streams on Bragger Family Dairy with data collected for seven years.

PHOTO 2: The monitoring locations were chosen to compare cropped acres to perennial grassland and woodland in a part of the state known for its steep-sloped, hilled landscape. Photos courtesy of UW Discovery Farms.