Lameness is one of the top welfare considerations and economic limitations in the U.S. dairy industry, negatively impacting involuntary culling rates, milk production, reproductive efficiency and overall costs of production. Each year with the arrival of late summer or early fall, dairy producers nationwide see a seasonal increase in lameness prevalence within their herds.

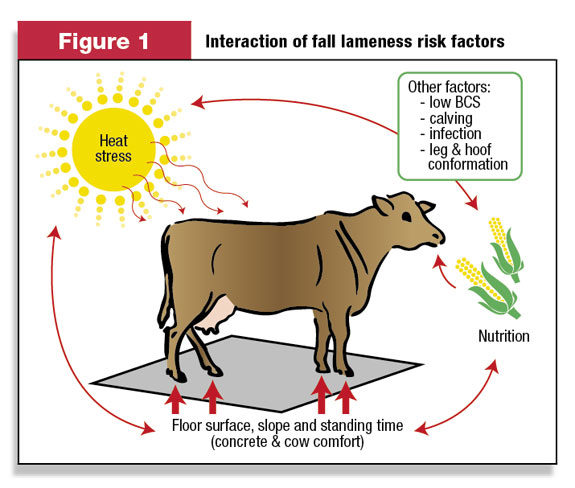

Fall lameness results from multiple factors. The primary factors contributing to this non-infectious, seasonal peak in claw horn lesions are heat stress, cow comfort and housing, and nutrition.

These factors (and potentially others) interact and the relative significance of each may vary from cow to cow and herd to herd.

Nevertheless, most herds can focus on three considerations as the major areas of risk and opportunity.

Heat stress

The significance and long-term effects of heat stress are sometimes underestimated; this problem is not just confined to Southern herds. A four-year study in Wisconsin revealed a very consistent and repeatable pattern between rising summer temperatures and increased claw horn lesions. Each year, lameness problems consistently peaked two to 2½ months after the summer’s hottest weather.

Referencing California dairies, Dr. José Santos of the University of Florida College of Veterinary Medicine has similarly noted that, “It is not uncommon to observe a high incidence of foot problems subsequent to a hot summer … dairy farmers and herdsmen routinely complain about an increase in lameness during the months of August, September and October.”

Recent research from the University of Arizona shows that high-producing dairy cows begin to experience heat stress earlier than previously thought – when the environmental temperature-humidity index (THI) reaches 68 (which equates with 72°F and 45 percent relative humidity).

As heat stress intensifies, cows breathe faster in an attempt to dissipate heat, sometimes to the point of panting or open-mouthed breathing. These increased respiratory rates are almost invariably accompanied by an increase in standing time.

Hot cows stand more – Wisconsin researchers showed that even mild heat stress increased standing time by approximately three hours per day. This is a critical component of the fall lameness challenge.

California and New Zealand researchers suggest hot cows stand more to increase the amount of skin (surface area) exposed to air and thus facilitate better convective and/or evaporative cooling. Furthermore, it is the author’s opinion that heat-stressed cows stand more because they can pant more effectively.

As a cow’s body contour changes when lying down, her lung capacity could be somewhat restricted by her rumen and abdomen as they push forward towards her chest. Standing relieves this pressure, so cattle may then be able to more easily exchange a greater volume of air and, thereby, more effectively get rid of body heat in the process.

Housing

One of the primary factors contributing to the development of fall lameness is the amount of time cows spend standing (see Figure 2 ), particularly if they are standing on concrete. Prolonged standing times increase the number of lame cows and the prevalence of claw horn lesions.

Dr. Chuck Guard of Cornell University notes that when cows stand on concrete, “pressure [is] exerted on specific portions of the claw [and] may contribute to the observed vascular-derived lesions of either hemorrhage or necrosis.

In addition to time spent standing, if the claws are not properly trimmed, localized pressure may contribute to further foot damage.” Thus, timely and proper hoof trimming is another key component to minimizing (and correcting) lameness.

Standing time is also highly influenced by facility design, and several factors combine to influence cow comfort and lying times. Ideally, high-producing cows are lying down at least 11 or 12 hours per day. If stall usage is unacceptable, producers should determine if there is a lack of bedding or padding for comfort, and/or if stall dimensions are incorrect (particularly inadequate stall width and/or lunge space).

Dr. Nigel Cook of the University of Wisconsin School of Veterinary Medicine has shown a 40 percent reduction in lameness prevalence when sand bedding is used instead of mattresses. During hot weather, stall-related limitations to cow comfort will be magnified if ventilation and cow cooling in the housing area are poor.

In addition to stall design, producers should determine if overcrowding is preventing subordinate animals (usually heifers) from accessing feed or, even more likely, having sufficient opportunity to lie down in a stall. Such animals are probably standing for excessive periods and may also be “slug feeding,” a situation that may lead to excessive variations in rumen fermentation and pH, and further predispose them to lameness.

Nutrition

Proper nutritional management is widely understood to be a key component in minimizing the incidence of sub-acute ruminal acidosis (SARA) that may contribute to the development of laminitis and its associated claw horn lesions. The most common risk factors are diets containing high concentrations of starch and other non-fiber carbohydrates (NFC) and low concentrations of forage and/or physically effective fiber.

Although improper ration formulation clearly may contribute to claw horn lesions, in and of itself it is not the only factor. In a past Progressive Dairyman article by Drs. Santos and Overton (March 2001), TMR and weigh-back samples were measured weekly in three large California dairy herds that had a high incidence of lameness (20 to 30 percent).

Concentrations of neutral detergent fiber (NDF) and NFC were adequate in all rations (NDF greater than 30 percent and NFC less than 38 percent). Ration particle size distribution was also acceptable (8 to 12 percent remaining in the top screen of the PSU particle separator) in all herds.

The investigators noted that even though these rations were believed to be “nutritionally safe,” white line separation, sole ulcers and abscesses (all claw horn lesions) remained a constant problem. These observations led the investigators to conclude that proper management of factors other than carbohydrate availability and diet particle size distribution may be extremely important for lameness prevention.

Sorting is one potential risk factor; another is altered daily eating patterns and fluctuations in intake common in heat-stressed cows. It is the diet the cow consumes, not the one formulated on paper, that matters most.

How do we address these challenges?

Most importantly, minimize heat stress by providing a cool, shaded, well-ventilated environment with adequate access to feed, water and comfortable bedding areas, so that animals are not standing for excessive periods and are maintaining normal eating patterns.

For the lactating cows, prioritize your heat abatement measures first and foremost in the holding pen. On most dairies, this is the hottest environment the cows experience, and time spent therein typically accounts for a substantial amount of daily heat gain. Remember that hot cows spend more time standing.

Minimize standing time, particularly on concrete. Limit holding pen time to a maximum of three hours per day, preferably less. Also beware of excessive time spent in headlocks, particularly for fresh cows. Consider rubber flooring for the holding pen and travel lanes to and from the parlor.

Beware of overstocking pens, where socially subordinate animals are less likely to achieve adequate daily resting times, particularly when combined with other factors that compromise daily time budgets. Make sure stalls are properly dimensioned and keep them well-bedded to encourage longer lying times.

Nutritionally, ensure a rumen-friendly ration is formulated and consumed (ration sorting and altered eating patterns can cause or contribute to problems). Summer rations should typically contain lower starch concentrations and/or less rapidly fermentable starch (remember that fermentability of the starch in corn silage and high-moisture corn increases with longer ensiling times), along with higher concentrations of both fermentable and physically effective fiber.

They should also contain adequate moisture and an appropriate particle size distribution to minimize the potential for sorting. Brown mid-rib (BMR) corn silage and BMR small-grain forages work well year-round, but they are particularly applicable to summertime feeding because of their high fiber digestibility.

Research supports feeding higher amounts of dietary sodium and/or potassium during heat stress to elevate dietary cation-anion difference (DCAD), whereby cows will improve their acid-base status as the buffering capacity of the rumen and blood is restored.

Also consider feeding additives such as biotin or organic/chelated zinc that are research-proven to benefit hoof health, and live yeast or yeast culture that will help maintain better rumen function during periods of heat stress. These approaches won’t eliminate the nutritional risks to foot health, but could help reduce the frequency and/or severity of the problem.

Fall lameness is a recurring and significant challenge on many U.S. dairies. The increased standing time exhibited by heat-stressed cows is the predominant risk factor in most cases, but other factors also contribute to this particular foot health problem.

Producers need to remember that the risk factors for fall lameness are additive, and thus should adopt a multi-pronged preventative strategy to minimize its impact. PD

References omitted due to space but are available upon request to editor@progressivedairy.com .

Bass is a veterinarian with 15 years of experience in dairy nutrition.

R. Tom Bass

Technical Services and Nutritional Support

Renaissance Nutrition

tom@rennut.com