In health and fitness circles, people are often encouraged to “know your numbers.” Key statistics like height, weight, body mass index, cholesterol and blood pressure numbers are often used as basic measurements – or at least benchmarks for embarking on a fitness program.

Likewise, when a dairy producer is describing his or her farming operation, a few key statistics are often recited: Number of cows, rolling herd average, butterfat percentage, somatic cell count, number of employees and so on. Not only do these numbers describe our businesses, they are a way to measure the quality of our work.

How do you measure the quality of your marketing decisions? So often, the management of price risks and opportunities takes a back seat to production management, and many producers do not have a systematic method for measuring the quality of their marketing decisions.

As dairies continue to become more sophisticated in their management processes, it is important to develop the right perspective on the markets and marketing decisions.

Just as a dairy’s rolling herd average is determined by the average of all cows in the herd, the price received for selling that production must be viewed in the big picture.

Producers can logically and unemotionally assess their marketing success by knowing their weighted-average price for their entire production over time.

What is weighted-average price? Weighted-average price is the net average price received over time for all of your milk production (or paid out for feedstuffs).

It is simply calculated by averaging the value of priced milk per hundredweight (cwt), the value of unpriced production assigned the current market value and the value of any milk with hedge positions.

Averaging these values is important because the price you receive for your production at any given point in time might be higher or lower than the current market price.

It should be your goal to make strategic and incremental sales (or feed purchases) that build the best possible weighted-average price for all your production long term.

W

hat does this look like, practically speaking? Let’s look at a producer who makes incremental sales over a period of time, and how each decision contributes to the weighted average for

the operation ( Tables 1, 2 and 3 ).

You can see how the weighted-average price adjusts by averaging in the price you receive for incremental sales during the time period. Y

our weighted-average price is dependent upon how much of your production you sold at any given price.

You can build a weighted-average

for your feed purchases as well, with the goal to incrementally lower your price paid for feed for the year.

Incrementally build your weighted-average price. Wouldn’t it be nice if we could lock in a profitable price and then forget about marketing for the rest of the year?

In reality, that would be like sorting cows into production groups at the beginning of the year and never revisiting them.

In order to capitalize on every opportunity the market offers, you need to make incremental decisions that gradually build the best possible weighted-average price for milk and feed. Doing so takes the pressure off each individual decision.

When I was explaining this to a friend of mine, he said, “So, it’s a little like ‘dollar cost averaging.’” That’s one way to look at it. When an investor sees an uncertain landscape, a financial adviser typically recommends “dollar cost averaging” into the marketplace.

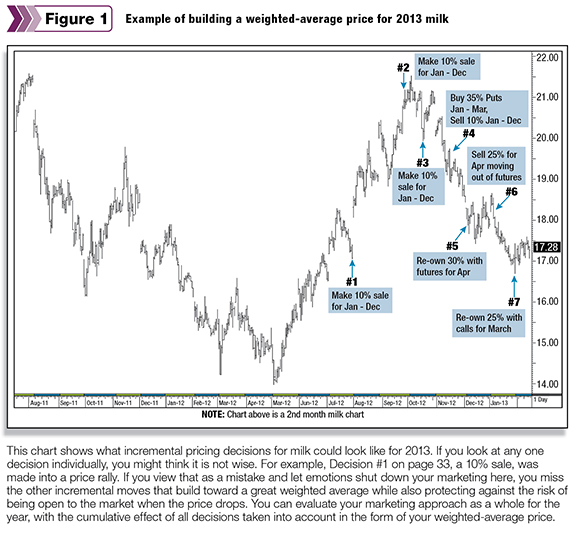

The theory is that by investing in increments over time, you eliminate the risk of buying at the top of the market. (See Figure 1 for example.)

The beauty of building the best possible price for milk and feed individually is that you are also incrementally building the best possible margin for yourself.

Rather than attempting to lock in a satisfactory margin, you are maximizing your opportunities and building the best price each market will give you, within reasonable risk parameters.

Use the weighted-average price to counter emotion. Your weighted-average price is a good tool for maintaining perspective on your marketing decisions.

It’s important to note that when we are in an “up” cycle for milk (for example, 2011), if you are consistently and incrementally capturing opportunity as a strategic marketer, your price during that upswing typically lags behind what the market has offered. At first glance, this might seem like a poor business decision.

Here is where weighted-average price and big-picture perspective comes in. Keep in mind that a chief reason for engaging in marketing is to protect yourself from the potential (ultimately inevitable) downturn in prices.

Historical data back to 1995 indicates that bearish downturns can be dramatic. The impact of being largely open to a $6, $8 or $12 price drop is far more damaging than being behind the market by a smaller amount in a bull market.

Do not be tempted to evaluate your marketing based on one sale or one relatively short time period. Unfortunately, some producers do not win the emotional battle and decide to bail out of their positions. Often, these producers end up bailing out near the top of the market and fully realize a price drop.

When you stay focused on building a solid weighted-average price over time, you can see whether your marketing decisions are meeting the long-term goals of your business. That’s the best way to eliminate emotional, knee-jerk decisions.

Evaluate future strategies by calculating the impact on your weighted-average price. Once you know your weighted-average price, you can create a calculator that helps you evaluate the impact that various strategies have had, or will have, on your weighted-average price in the future.

For example, what would selling 20 percent of your production at $18.50 look like? Then, if you sell another $18.25 and also purchase calls, what would that look like?

When using weighted-average price to evaluate strategies, you have to consider that the milk price is a moving target. If you sell 20 percent of your production at $18 and the milk price goes to $21, what is your average price?

If your average price would stray too far from the market price, then maybe call options or an alternative strategy is needed. Weigh each strategy against multiple milk price scenarios, so you can see what the strategy does to your weighted-average price no matter which way the market moves.

We are constantly charting these strategies, so that we can “rehearse the future” with clients in advance of a market move. “Rehearsing the future” is a concept described by author Peter Schwartz in his book, “The Art of the Long View.”

That’s what we’re going for here – the long view and long-term success. Widen your perspective on marketing decisions, and it will help you in the long run. PD