Sometimes the most interesting and worthwhile films aren’t the ones on the marquee at your local cineplex. That’s especially the case if you’re a farmer looking for a film you can relate to or are someone who cares about farming as a way of life.

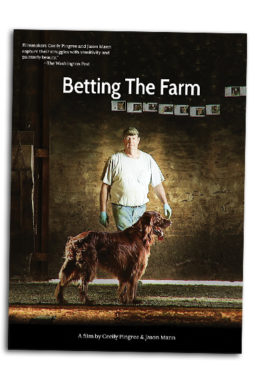

One such film is making the rounds at select locations but is also available for purchase on iTunes, and it’s called “Betting The Farm.”

Directed by independent filmmakers Cecily Pingree and Jason Mann, in 84 minutes it beautifully conveys the story of a group of small organic dairy farms in Maine that received a most unwelcome piece of mail in March of 2009.

Click here to read PD Editor Walt Cooley's review of the movie.

The letter was from milk processor H.P. Hood, which a few years earlier had convinced a bunch of Maine dairy farms – some organic, some conventional – to supply the company with organic milk.

Aside from the prospect of higher margins, Hood lured them in with the promise of paying for trucking the milk to the plant, a substantial cost because some of these farms were hundreds of miles away from the nearest organic processor, which is in New York.

But when more New York dairies switched to organic, Hood realized it didn’t need the Maine farmers anymore. The March letter said Hood was terminating their contract, effective in October of that year.

“We thought we were in this for the long haul,” explains Maine farmer Vaughn Chase in the film. “Then we got the letter and we were like, ‘Wow, what do we do now?’” Chase had a family to feed and had just replaced his 25-year-old tractor. The timing couldn’t have been worse.

Two gentlemen at the Maine Farm Bureau – Rommy Haines and David Bright – heard about this problem and offered to help the farmers find a place to process their milk.

Then they hooked up with agricultural consultant Bill Eldridge and came up with an even bigger plan: form an independent, farmer-owned company that could process, bottle and sell the milk under its own brand name. Somehow they got the 10 farmers Hood dropped to sign up, and Maine’s Own Organic Milk (MOO Milk) was born.

The first challenges were to replace the central services Hood performed for the farmers – trucking and processing.

By a stroke of luck, Smiling Hill Farm in Westbrook, Maine, had an organically certified processing facility that MOO Milk could use. And then the company made a deal with Portland-based Oakhurst Dairy for sales and distribution in Maine.

But those turned out to be the easiest problems to solve. As the film makes clear, it was much harder to build up the distribution to a level where the company could pay its farmers a liveable wage.

When the first six months had gone by and the 10 farms were late on their mortgage payments and other bills, frustration and impatience mounted. Farmers phoned each other, trying to gauge if their colleagues were going to give up.

Board meetings became tense shouting matches. As Chase notes during the film, “You know, I’ve never been involved with anything with a group of farmers, but [......] it’s an awful mess.”

A combination of factors helped MOO Milk ascend from those depths. First, the entity was formed as an L3C: a low-profit limited liability company.

This allowed MOO Milk to get investments from non-profits and foundations yet still retain an ownership structure where farmers have equity.

One crucial investor is Coastal Enterprises Inc., which is dedicated to improving the economy of rural Maine. An investment in early 2012 actually saved the company from folding by providing money for expanding distribution and increasing sales.

MOO Milk has also benefitted from its high-quality product and gained a reputation as a great-tasting milk with a good story.

According to David Bright, who is the deputy treasurer of the company, about half of the sales come from people who want to support local farms, while the other half come from devoted organic milk drinkers.

Some people feel so strongly about the milk that they volunteer on the “MOO Crew,” a group of 30 or 40 customers who make notes of inventory, product placement, pricing and dates – and then report back to the MOO Milk office.

For now, the MOO Milk story has a happy ending. The group has grown to include 12 farms, and two more will join by the fall. MOO Milk is sold in more than 200 stores in New England, including every Whole Foods store in the region.

A new round of investment came in April, which will pay for media advertising and processing machines that can package in more sizes.

Perhaps most importantly, the farmers are receiving $27.50 to $36 per hundredweight for their milk depending on the quality bonus, which is just about a sustainable wage.

To me, MOO Milk is another example that if farmers want an alternative to the conventional path, and they make a high-quality product, consumers will respond. “Whether you like this type of business or not,” says Chase, “probably someday we’ll be forced to be more localized. It only makes sense.” PD

Kardashian is a senior writer at the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth and the author of “Milk Money: Cash, Cows, and the Death of the American Dairy Farm.”

Kirk Kardashian

Senior Writer

Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth