Through years of neutral detergent fiber digestibility (NDFd) work, it is clear there are multiple pools within the neutral detergent fiber (NDF) of forage fiber. Currently, we are focused on three pools: fast, slow and “indigestible.”

Work at Cornell University under Mike Van Amburgh has shown that the 30-, 120- and 240-hour time points best characterize the digestibility/undigestibility of NDF across all forages.

The NDF that ferments within 30 hours makes up the fast pool, from 30 to 240 hours makes up the slow, and the 240-hour residue is considered to be the best estimate of the indigestible portion of NDF.

Why the hype over uNDFom240?

Working in collaboration with Cornell and the University of Bologna, the Miner Institute conducted a study in 2011 designed to look at how forage particle size and digestibility affect rumen retention and passage time.

The study design involved feeding high-forage (greater than 65 percent) versus low-forage (less than 52 percent) diets using highly digestible NDF (BMR corn silage) versus less digestible corn silage (24-hour NDFd values of 58 percent and 40 percent, respectively).

Analysis of the whole TMRs and rumen contents for uNDFom240 provided some surprising results. The amount of uNDFom240 (uNDF terminology for a 240-hour in vitro digestion) held in the rumen was in near-constant proportion (1.57 to 1.6) to the amount of uNDFom240 cows consumed across all four diets.

To determine if these results were just chance, we analyzed TMRs and rumen contents from a study conducted three years prior where the diets decreased in percent forage from 52 to 39 percent by replacing corn silage (CS) and haycrop silage (HCS) with non-forage fiber sources such as dried distillers grains, wheat midds and straw.

Of the four diets, three resulted in the similar proportional relationship of rumen content to intake of uNDFom240 of approximately 1.6. In short, of eight vastly different diets, in trials conducted three years apart, ranging in source of NDF, a near-constant relationship between rumen fill and intake of uNDFom240 was observed.

Based on the 2011 trial and a 2.5 kg (approximately 5 pounds 8 ounces) drop in DMI and 4.5 kg (around 10 pounds) drop in milk production of the high-forage/low-digestibility diet, we postulated that intake of uNDFom240 at 0.4 percent of bodyweight might be a gut fill maximum whereby DMI is reduced.

And if intake of uNDFom240 was less than 0.3 percent of bodyweight, that risk of sub-acute ruminal acidosis might be incurred with high-production dairy cows. It turns out these values may only be appropriate for the high cows.

Rumen fill flux

There is much discussion of the value of uNDFom30 as a factor in DMI, which we agree with, but understanding the value of knowing the quality of the slow pool (uNDFom30 – uNDFom240) and “indigestible” uNDFom240 pool may improve our ability to estimate gut fill limits of maximums and minimums.

For discussion point, let’s assume a high-production dairy cow consumes one day’s worth of TMR in one meal instantaneously. This is time zero of her day. If that whole TMR is 50 percent NDFd30 (or vice versa, 50 percent uNDFom30), that means 50 percent of the NDF, the fast pool, is fermented to volatile fatty acids, CO2 and CH4; it is gone, which makes space for her to eat more the next day.

However, there is still some undigested TMR taking up space in her rumen. The question becomes: How long will it stay there taking up space?

Can we analyze the diet and estimate how long it will take to clear that undigested feed? Possibly. If we know the iNDF portion as estimated by uNDFom240, we can estimate the size of the slow pool and rate of its degradation through microbial fermentation.

In other words, we are trying to characterize the quality of the slow NDF pool to determine rumen residence time in order to avoid a rumen fill backlog of slow uNDF. It’s all about making space for the next day’s worth of DMI.

Case scenario

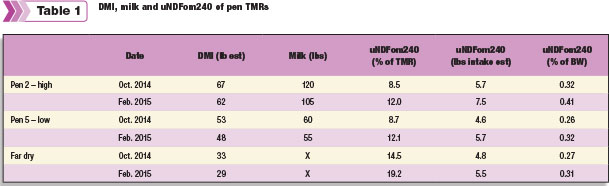

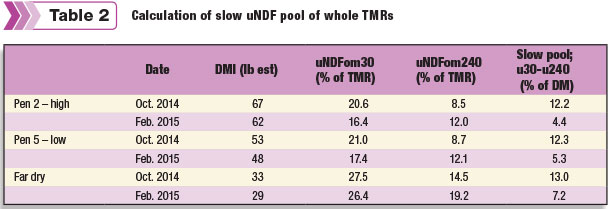

In Oct. 2014, we took TMR samples from the feedbunks of our high, low and far dry cow groups (Table 1 and 2). Cows were eating and milking well; forage quality was good, and corn silage was from 2013. In February 2015, we needed to start conserving CS and increase HCS in the rations.

Click here or on the iage above to view it at full size in a new window. (PDF, 4.6 MB)

We also were faced with feeding new crop-year (2014) corn silage, much of which had been frost-damaged. So diets increased in grass and switched from good CS to poor CS.

Cows did not take long to show the effects of this diet change, with decreased DMI in all groups and a severe drop in milk. Both the high- and low-group cows dropped 5 pounds of DMI and 15 and 5 pounds of milk, respectively. The far dry cow group dropped 4 pounds of DMI.

Click here or on the iage above to view it at full size in a new window. (PDF, 3.8 MB)

Analysis of the uNDFom240 of the whole TMRs, in retrospect, shows that the whole TMR uNDFom240 increased about 4 percentage units for both the high and low groups and almost 5 percentage units in the far dry. As a percentage of bodyweight, the high-group cows were at the proposed gut fill limit of 0.4 percent bodyweight of uNDFom240. The low-group and dry cows showed depressed DMI at about 0.3 percent of bodyweight.

Clearly, reference point of gut fill maximum for intake of uNDFom240 differs between high cows and low and dry. If we look at the uNDFom30 values of these TMRs, we see that in February 2015, they were actually lower, less undigestible/more digestible than in October 2014. If the uNDFom30 were the primary determinant of intake, then cows should have increased DMI in February 2015.

Here is where the quality of the slow NDF pool matters. With higher levels of uNDFom240, “iNDF,” the slow fiber pool on grass and poor-quality CS in February 2015 was worse than the slow fiber pool of October 2015.

It was simply building up in the rumen, creating a new, higher set point of rumen fill, thereby limiting the rumen space available to take in more DM. Even though the slow pool was larger in October 2015 TMRs, it had to be more digestible.

Forage vs. TMR uNDF

Note that much of this discussion has been based on uNDF analyses of whole diets. The labs are set up to provide NIR of forages only, not whole TMRs. Therefore, reference values of uNDF fill maximum and minimum need to be calculated on forage-only basis and tracked for your farm, your management, your cows’ time budgets, bunk space availability, etc.

We suggest you work with your nutritionist to start tracking all groups for uNDF consumption to determine values when cows are healthy and at peak production and when they are not. PD

-

Kurt Cotanch

- Forage Lab Director

- Miner Institute

- Email Kurt Cotanch