Accommodating cows’ behavioral needs, or time budget, is essential for their welfare and their overall productivity.

In the “big picture,” the physical factors of the facility (stall design, flooring type, feedbunk design, environmental quality) impose baseline limitations on how cows will interact with housing conditions. After these facilities limitations, the behavior of cows is further dictated by management routines such as grouping strategy or stocking density.

If time budgets are key, what do we know about them?

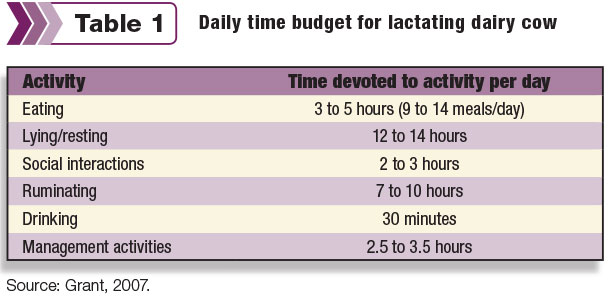

For freestall-housed, parlor-milked herds, data from Miner Institute established that lactating dairy cows will spend 12 to 14 hours per day resting (lying) and three to five hours per day feeding (Table 1). These basic behaviors fill 60 to 80 percent of a 24-hour period, which leaves a limited number of hours for milking and other management procedures.

A study across 16 commercial farms in Wisconsin observed cows spent 12 hours per day resting and 4.5 hours per day feeding, which provides further support for the idea that lactating cows having a consistent time budget – or at least attempt to.

Dairy cows milked in robotic milking systems may have slightly different time budgets. In a study using Swiss dairy farms, cows spend 7.1 hours per day in the feeding area and 11.8 hours per day in the resting area. Of the time spent in the resting area, 10.6 hours per day were spent lying down.

Similarly, time spent in the feeding area does not necessarily reflect true feeding time. In the study, for example, the farm in which cows spent the longest time, on average, in the feeding area used a “feed-first” cow traffic pattern, i.e., cows had to enter and pass through the feeding area to be milked.

What affects the lying portion of cows’ time budgets?

If we accept this general concept of time budgets, then it becomes important to understand the various aspects that can alter how a cow spends her day. To begin with, we must recognize that while the average time budget seems relatively consistent across various studies, individual cows will be highly variable. In a study conducted on 45 farms in British Columbia, individual lying times ranged from as little as four hours per day to more than 19 hours per day.

Despite this wide range, the average lying time per day for all farms was still 11 hours per day. A follow-up study involved farms in British Columbia, California and the Northeast U.S. and determined that bedding management, stall stocking density and rubber flooring were all facility-based factors that affected daily lying times.

Days in milk was the only cow-based variable that consistently explained differences in lying time. In two separate studies, cows in the later stages of their lactation had greater lying times, which was thought to be driven by decreased feeding time (associated with the lower energy demands of decreasing milk production), leaving more time available for resting.

On the other hand, at Miner Institute it was observed that for each additional hour of lying time, milk yields increased by approximately 3.5 pounds per day. This is one of the contradictions of lying time that merits more investigation to fully establish the role of lying time in productivity and why cows seem to spend more time lying in the later stages of lactation.

It is well-established that feeding frequency and timing of feed delivery can influence feeding times. While the initial studies were conducted with 2X milking, more recent work from the University of Guelph determined that dry matter intake could be increased by increased feeding frequency on farms milking 3X daily.

Additionally, primiparous cows consumed smaller meals at a slower feeding rate, relative to multiparous cows, within mixed pens of primiparous and multiparous cows fed 3X, 2X or once daily.

This resulted in primiparous cows consuming between 25 and 50 percent less dry matter during their first meals following the first two milkings of the day. These inherent differences in feeding behavior suggest that primiparous cows may need special consideration to meet their behavioral needs within commingled pens.

New considerations for time budgets

Recently, predicting the onset of disease was a major focus related to cows’ time budgets. A series of studies from the University of British Columbia reported decreased feed intake and feeding time before calving and during the first week or so after calving could predict cows at the greatest risk of developing clinical and subclinical metritis and subclinical ketosis.

For diseases more common beyond the transition period, there were still behavior changes evident. Data from the University of Wisconsin observed sound cows spent 21 minutes more per day feeding compared to slightly lame cows and one hour more per day than moderately lame cows.

Additionally, lameness alters meal size and length. The onset of experimentally induced mastitis decreased feeding time over the first 12 to 24 hours. The effect of the onset of mastitis on lying behavior is more complex.

Contrary to the general model of sickness behavior in cattle, cows with E. coli mastitis decreased their lying time on the day the disease was induced. However, mastitis induced by S. uberis increased lying times. This suggests that effect on time budgets from mastitis might be pathogen-specific rather than one that can be generalized.

Some recent work done in Sweden may bring on the biggest changes in how we understand the time budgets of cows. Researchers at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences were able to develop a means to evaluate REM sleep in cows and confirmed that a portion of their lying time was spent engaged in true sleep.

In the present state, the equipment is too cumbersome to be used for the evaluation of sleep in loosely housed dairy cows. However, if successfully developed, this type of technology will provide a means being focusing on the quality, not just the total amount, of lying time.

Final thoughts

While there are some differences across farms and cows, we can conclude that lactating dairy cows have a daily time budget based on approximately 12 hours of lying or resting each day and about four hours per day of feeding.

Keeping this in mind when evaluating management activities, such as time away from the pen or time spent restrained within headlocks, and management strategies such as stocking density or bedding, should promote the overall welfare and productivity of your herd.

Beyond evaluating facilities or management, time budgets will likely have a greater and greater role in disease diagnosis, as our understanding of how cows alter this behavior when they become sick makes this a more usable aspect of commercially available activity monitors.

On the other hand, the idea of studying the need for sleep of dairy cows may represent an area that will revolutionize how we think about what a cow needs from her environment and how she spends her time. PD

-

Peter Krawczel

- Assistant Professor

- Department of Animal Science

- University of Tennessee

- Email Peter Krawczel