The incorporation of commercial rumen-protected amino acids in dairy diets has been growing since the early 2000s.

The three main reasons for that include the release of the 2001 NRC’s Nutrition Requirements of Dairy Cattle, the availability of commercial software programs to balance the nutrient profile in dairy rations and the implementation of the Federal Milk Marketing Order (FMMO) milk pricing.

The former brought to light not only that amino acids are required nutrients but also clearly determined that lysine and methionine are the first two most limiting amino acids in dairy rations in order to optimize milk protein production.

Current knowledge concludes that other amino acids beyond lysine and methionine may be limiting the genetic milk production potential of the modern dairy cow; histidine seems to be co-limiting with the first two amino acids.

Second, the use of software programs to create least-cost rations allows the nutritionist to strategically add rumen-protected amino acids in order to optimize milk production.

The initial work evaluating amino acids in lactating cow diets has focused on estimating the response of increased milk protein production or milk volume.

Results from more than 40 years of research clearly demonstrate that when diets are properly balanced for amino acids, cows respond with higher milk production or component composition.

Third, since the implementation of the milk payment scheme by the FMMO in 2000, some regions adopted a pricing formula that pays for components.

Except for a few short periods of time, milk protein makes up for at least 50 percent of the final mailbox milk price. Private nutritionists and feed companies have implemented the practice of using rumen-protected amino acids in the FMMO regions that pay for components.

The answer is ‘yes’

When the use of rumen-protected amino acids are specifically implemented to increase milk protein production, the question often asked is: How long will it take cows to respond to added rumen-protected amino acids to their diets?

The answer is: “Yes.” Often, we forget that amino acids are not just the building blocks of protein or, in this case, the building blocks of milk casein.

Amino acids are required nutrients, as some participate in key aspects of the cow’s metabolism, which has an impact on health and reproduction.

In 2010, Dr. Guoyao Wu introduced the concept of “functional amino acids” to identify those amino acids that participate and regulate key metabolic pathways that improve health, survival, growth, development, lactation and reproduction.

Although this concept was originally tested in other species, recent research trials showed that ruminants respond with more than milk when fed diets enriched with rumen-protected methionine sources.

Results of trials during the transition period demonstrated that cows fed the methionine-enriched diets have benefits to the cow in more than one way.

The results from those trials demonstrated that cows offered rumen-protected methionine-enriched diets increased dry matter intake and responded with higher milk production and composition.

However, most importantly, those cows were less prone to inflammation and showed lower somatic cell counts. Cows do respond to amino acid-balanced diets; the time it takes them to respond depends on the expected outcome.

It takes hours, days, weeks, months or even a few years

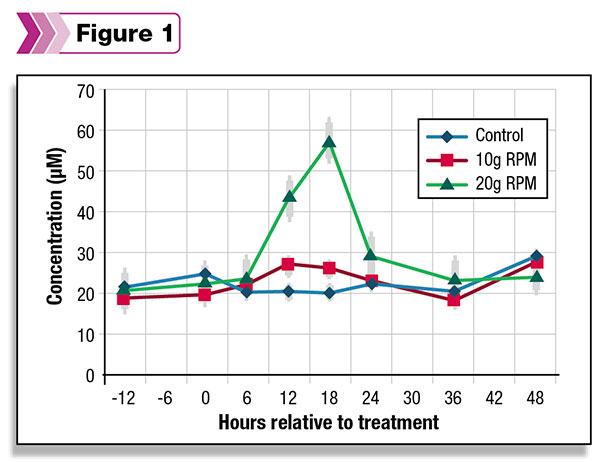

The plasma concentration of amino acids increases within hours. A trial conducted at the University of Wisconsin characterized the changes in plasma methionine after administration of a single bolus of zero (control), 10 or 20 grams of a rumen-protected methionine (RPM) source.

Researchers demonstrated that there is a significant increase of plasma methionine as early as 12 hours after administration. In addition, the increase in concentration was proportional to the dose (Figure 1).

However, as stated earlier, amino acids participate in many different functions besides solely acting as building blocks of proteins (i.e., casein, muscle, enzymes).

However, as stated earlier, amino acids participate in many different functions besides solely acting as building blocks of proteins (i.e., casein, muscle, enzymes).

Some amino acids act as signals to elicit metabolic responses affecting the immune system by altering gene expression or affecting embryo development. In the specific case of building blocks of milk protein, it may take a couple days to elicit a noticeable response.

In a trial conducted in the UK, researchers fed an amino acid-adequate diet or an amino acid-inadequate diet to cows at two different stages in their lactation cycles. The cows were fed a basal diet supplemented with fish meal to provide all the required amino acids to support milk production.

After a few weeks, the fish meal was replaced by feather meal – a protein source with a very poor amino acid composition. Milk protein production dropped within a few days.

After four weeks on the feather meal diet, the protein concentrate was switched back to fish meal, and the cows increased milk production to the “original” basal production within two weeks. These results demonstrated that under controlled conditions, the milk protein response from cows happens rather quickly.

Further, the time it took to respond was independent of the stage of lactation. The trial was conducted with cows at six and 22 weeks into lactation; both responded similarly.

Under a commercial situation, when the conditions may not be as controlled, it may take a few weeks to observe a noticeable response. However, on an individual cow basis, the true “milk” response happens within a few days.

Results from trials conducted at the University of Illinois demonstrated that when cows are fed amino acid-balanced diets during transition, cows responded with an immediate increase in milk production.

Compared with control cows, the cows fed a methionine-balanced diet produced an average of 8 to 10 pounds more milk during the first 28 days of lactation. The fresh cows showed increased dry matter intake and had lower somatic cell counts.

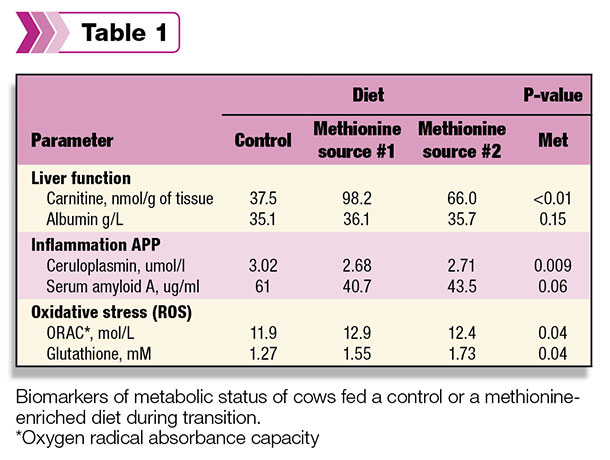

Based on plasma concentrations of different biomarkers, cows fed the amino acid-enriched diets were in better metabolic status, suggesting they were better prepared to withstand calving and early lactation stress (Table 1).

From a practical point of view, the benefits of these outcomes are hard to capture in a short time period, since there is always a relatively low number of fresh cows, and it takes many cows to estimate the incidence of a metabolic-related disease in the herd.

From a practical point of view, the benefits of these outcomes are hard to capture in a short time period, since there is always a relatively low number of fresh cows, and it takes many cows to estimate the incidence of a metabolic-related disease in the herd.

Despite the fact that the individual cow response to an amino acid-balanced diet may be rapid, it may take weeks to a few months to capture enough information to assess the impact on the metabolic responses of the herd. Accurate records are key to assessing transition from the dry period to full production.

A trial conducted at the University of Wisconsin evaluated the impact of feeding a rumen-protected methionine-source diet from calving to pregnancy in regards to embryo quality.

Cows fed a methionine-deficient or methionine-enriched diet from calving to pregnancy were heat-synchronized and super-ovulated with the intention of collecting several embryos per cow at 73 days in milk.

The harvested embryos were evaluated on quality – as viable or non-viable – in order to test the hypothesis that the cows fed the methionine-enriched diets would produce higher-quality transferable embryos.

There were no differences in the number of viable embryos or quality of the embryos; however, there were differences in gene expression and DNA methylation of the embryos harvested from the dams fed the two diets.

The authors concluded that supplementing methionine to dams prior to conception and during the pre-implantation period modulates gene expression in bovine embryos.

It has been recognized that amino acids are essential to warrant normal early embryonic growth in different species. However, until recently, the hypothesis had not been studied in lactating cows.

Results from a trial conducted at the University of Wisconsin indicated that feeding a rumen-protected methionine source – from calving to the second pregnancy check at 60 days after breeding – has a positive impact on embryonic growth and may aid in preventing early embryonic losses.

In a commercial herd, the full appreciation of the beneficial effects of achieving pregnancies takes several months. It will take a few years to evaluate the epigenetic effects induced in the progeny of the dams fed the methionine-enriched diets. PD

Daniel Luchini is the manager of ruminant product technical services for Adisseo, has a Ph.D. in dairy science from the University of Wisconsin and has received seven U.S. patents.

References omitted due to space but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.

ILLUSTRATION: Illustration by Sarah Johnston.