Editor’s note: This is the second of a two-part series discussing how Montana’s supply management system operates and the effect it has had on the state’s dairy industry.

In the last article, I introduced Montana’s supply management policy, also known as quota. Click here to view the article.

To briefly recap: Montana is the only state in the U.S. with effective supply management, which has kept annual production around 280 million pounds since 1990.

The amount of quota available has not changed since its institution, so farmers can only acquire more when others decide to sell, and price of quota varies based on demand.

Quota ownership ensures farmers receive the highest pooled price for the corresponding amount of milk produced.

So what does this mean for producers? How has quota impacted their on-farm decision-making? And in what ways do Montana dairy farmers think quota has affected the state’s industry?

I wanted to know the answers to these questions, and because I was in graduate school, had dairy experience and wanted to study Montana dairies, a thesis attempting to understand the above questions was the perfect solution.

In 2012, I began my research and in May 2013 completed and defended my thesis. I interviewed 17 dairy farmers from across the state, which included two retired farmers and one who processes on-farm.

From the 14 farmers that are currently shipping milk, 12 are affiliated with Darigold and two with Meadow Gold. The size of the dairy herds reflected the range found in the state, from milking around 50 to more than 700 cows, with an average herd size of 268.

All of the farmers are the primary owner-operators of their farm and have been in that role for an average of 30 years.

Previous research from Canada and Europe discussed three primary effects of quota: cost, lowered competitive advantage and changing on-farm structural adjustment (for things like building new barns or putting in more advanced equipment).

Results from these studies show that farmers are no less likely to upgrade their equipment but do spend more on operations than farmers in non-quota systems. A major effect was the potential loss of competitiveness with regions that do not use supply management, particularly when there are free-trade agreements.

Using these findings as a guide, I developed questions that would speak to the known effects of quota while also letting farmers share their thoughts.

So what did Montana dairy farmers talk about? Cost of quota was a major, and often heated, topic of discussion, with 14 of 17 farmers bringing up the high cost at least once. The three farmers who did not discuss cost have some of the smallest herds in the state and have remained at or near their initial quota levels.

Many farmers related buying more than 10,000 pounds of quota during the period when it was selling for $21 to $26 per pound. One farmer explained how quota affects his costs by saying, “If you have an 80-pound herd average, it costs you $2,000 to buy the quota for one cow at $25 [per pound].

At $10, it would be $800. So it still costs me $800 every time I want to buy a cow, where in a non-quota system, that is not part of the equation.”

Nine farmers brought up the issue that they think it is almost impossible financially to produce milk in Montana without quota. Over-quota milk is priced $1.50 lower than the highest blend price.

When milk prices are high, the lower over-quota price is not so detrimental, but when milk prices are low, the differential can be the difference between making and losing money.

One farmer explained, “when you are down to $15 [per hundredweight] and your excess is 13 and a half, then your margins are tighter, so you would like to have that extra $1.50. It probably becomes more important to us at that point to have our quota pounds and our production about the same.”

Since farmers were given their quota for free when the system was initiated, some thought it might have enticed farmers to exit the industry earlier than they may have otherwise.

One farmer explained that they had been “handed thousands of dollars of bonus that they could then sell,” while another noted that in the early years “virtually everyone that was selling quota was getting out.”

While quota may have encouraged some people to retire, farmers felt that quota may have also created a situation that discourages new producers.

Several farmers noted that they could not think of one new dairy farm since the start of quota, with one farmer saying, “It is keeping young dairies from starting because it is expensive to get it.”

Farmers did report benefits from the quota system, including protection and stabilization for Montana’s dairy industry. Because the quota system in the state requires processors to first utilize Montana milk for Class I fluid use, it provides a guaranteed market for dairy farmers.

Without this, many farmers I spoke with felt like Montana would be flooded with out-of-state milk, particularly given the proximity of Idaho and Washington. Smaller farmers felt like quota has protected them from the bigger dairies because everybody’s milk is worth the same amount.

Farmers also noted the stability quota has provided, which is practically unheard of in the U.S. dairy industry. Not only has it ensured a market, the quota system has encouraged farmers to produce at a level matching their quota, which makes it easier for processors to plan.

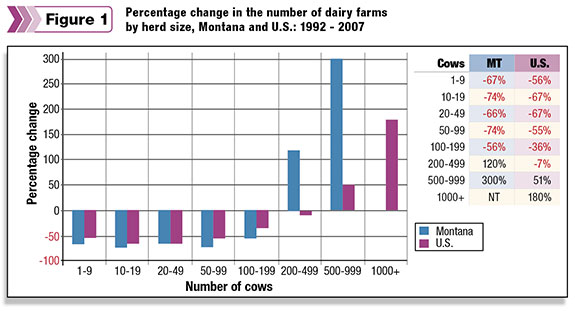

It would be easy to assume that in areas with supply management, there would be a greater number of small farms when compared to non-quota areas because of the equalized pricing, but Montana is actually losing these farms at a rate slightly faster than the national average.

The Montana industry is growing in the mid-scale category of 200 to 499 cows, where on the national level, this scale is also declining. The category of 500 to 999 cows shows explosive growth in Montana, but this is slightly misleading because it is only a change from one to four farms.

While there are no dairies in the state that have herds of 1,000 or more cows, it may only be a matter of time, as more farmers continue to retire and the remaining dairies increase their herds.

So the question remains: Are supply-managed dairy industries more stable and better off than free-market dairy industries? In Montana’s case, this question is difficult to answer because it is one state in a dairy-producing nation.

Because Montana operates with the Federal Milk Market Order (FMMO) pricing as a guide, it is not entirely separated from national and international supply and demand signals, and quota on its own does not necessarily affect the farm-gate price of milk.

Also, Montana cannot turn away dairy products from other states, so the market sells both Montana-made and imported dairy products.

Despite this, Montana’s dairy industry is not thriving. A continued loss of farms, processing only for fluid milk and uncertainty about the future still haunt the state’s dairy farmers.

When asked about the future of Montana’s dairy industry, farmers answered one of two ways: Three farmers said it is going to stay exactly the same as it is now, while 14 thought there will be fewer and bigger farms.

As it stands currently, quota may be helping Montana dairy farms stay viable in the near future, but questions about long-term survival remain.

On a national level, supply management of the dairy industry may make sense, but there are a lot of variables to consider. The U.S. generally prides itself on a free-market economy, and supply management is the antithesis of that.

Some farmers feel as though supply-managed systems cause consumer prices to rise, which is the case in Canada, and that in itself would make a national quota system unlikely to pass. The other issue with a national quota policy is whether it would control all milk, like Canada’s system, or only fluid milk, like Montana’s system.

If controlling price swings on the farmer’s end was the goal, then a system like Canada’s would be a better fit. If the U.S. wanted to limit Class I production and keep it more in line with demand, then perhaps a system like Montana’s would work better.

On the other end of the spectrum, the U.S. could remove subsidies, tariffs and FMMOs and let the dairy industry operate under a free-market policy. New Zealand did this in the 1980s, and since then farmers have learned to respond to international market signals and adjust their production accordingly.

The effects of supply management vary by farm size and intent of the farm operator, and change the ways some farmers make decisions on their farm.

Understanding the ways that quota affects individual farmers may help lead to better, more responsive dairy policy in Montana and on the national level.

But for now and into the foreseeable future, Montana dairy farmers will operate under their supply management system. While most of Montana’s dairy cows might be black and white, the issue of supply management is not so clear. PD

Laura Ginsburg earned her M.S. from the University of Montana in 2013. She received a Fulbright scholarship to study dairy policy in New Zealand for 2014 and is also starting a small dairy in Montana.

Several farmers noted that they could not think of one new dairy farm since the start of quota, with one farmer saying, ‘It is keeping young dairies from starting because it is expensive to get it.’ Illustration by Kevin Brown.