Editor’s note: This is the first of a two-part series discussing how Montana’s supply management system operates and the effect it has had on the state’s dairy industry.

From overlooking Glacier National Park in the west to the seemingly never-ending expanse of blue sky in the east, Montana dairy cows have some of the best views that can be found in the state, rivaling what many people see from their home or office windows.

In some places, there is only open space as far as the eye can see, while in others development and houses crowd the surrounding land.

And depending on what part of the state you are in, there might be another dairy just down the road, or it might be 200 miles or more before you come to the next one.

But it is not only the picturesque landscapes which set Montana dairying apart from other states – it also has a unique industry overall because it is one of only two states which utilize supply management.

Dairy farmers across the state literally have to “pay to play” by purchasing quota, or production rights, in order to sell into the higher-priced fluid milk market.

With only 70 dairy farms left across the state, the industry is just a shadow of what it used to be. Farmers and long-time residents tell stories of a time when there were dozens of dairies in areas where there may now be only one or two.

This will come as no surprise to those familiar with the dairy industry; since the 1980s, there has been a constant decline in the number of dairy farms across the U.S., an approximate loss of 3 percent annually.

According to Montana’s Milk Control Bureau, there were 218 dairy producers in 1990; by 2012, there were just 70, a 68 percent decline.

Also, only three processing plants remain in the state: Darigold, a cooperative based out of Seattle, operates one in Bozeman, while Meadow Gold, a subsidiary of Dean Foods, operates creameries in Great Falls and Billings.

While Montana generally mirrors national trends in terms of consolidation of farms, it stands out for its use of a mandatory supply management policy intended to keep production steady.

California is the only other state that utilizes supply management, yet the system has not been as restrictive as Montana’s and is considered a modified pooling mechanism rather than true supply control given the amount of milk produced over the set quota.

And unlike Canada, which regulates milk supply for all dairy products, Montana’s quota only affects Class I milk that is shipped to a processor and sold as fluid milk in a bottle.

In 1990, Montana established a quota system in which farmers own the rights to produce a certain amount of milk on a daily basis and receive the highest pay for that production.

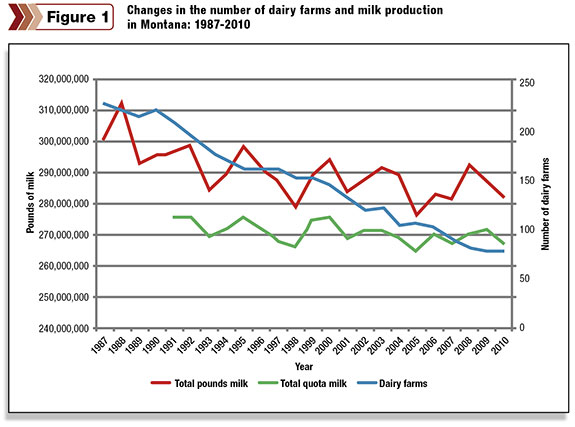

As illustrated in Figure 1 , the quota system has kept milk production in the area of 280 million pounds annually while farm numbers have continued to decline.

Despite changes in the industry and population growth in the state from just under 800,000 in 1990 to 989,000 in 2010, and thus increasing demand for dairy products, Montana’s dairy production has been fairly stable for nearly two-and-a-half decades.

Consistent with national trends of fewer and bigger farms, as the total number of dairies declined in Montana, the amount of milk produced has stayed level, indicating that as farmers exit the business, those that remain increase their own production.

Montana dairy farmers and the Department of Livestock adopted the quota system and production pool in Montana in 1989 and enacted it in 1990, with the original intent to limit producer production. Before the institution of quota, farmers typically held a shipping contract with a specific creamery for a certain amount of milk.

If the farmer wanted to significantly increase his or her herd, they would have to contract with the creamery to do so.

Each creamery had its own utilization levels for various value-added products, which later factored in heavily into the formation of the quota system and created the need for a production pool.

All milk produced in the state that is shipped to a processor constitutes a “pool” available for processing. The pool and quota are inextricably linked, as one would not work without the other.

The pool is significant because before its inception, producers were paid differently depending on which plant processed their milk.

Historically, when there were more processing facilities across the state that made dairy products other than fluid milk, such as cottage cheese and ice cream, producers received different amounts for their milk.

Once the pool was initiated, it no longer mattered which company the farmer was working with because all milk in the state was essentially combined and the total usage derived from that larger amount.

Now usage and payout is based on the Class I utilization of both Meadow Gold and Darigold combined, so even though Meadow Gold currently has higher amounts of Class I usage, all producers benefit.

Upon implementation of the quota system, each producer was given a percentage of their existing production as quota pounds, which was based on the producer’s highest total production for the year preceding quota implementation.

Because quota only affects Class I, or fluid milk production, the percentage was calculated based on the utilization of the plant they were currently shipping to and how much of that milk was going to fluid uses.

Producers for Meadow Gold received 100 percent of their production, while Darigold producers received about 75 percent, which created an immediate demand for additional quota pounds.

Quota pounds are for daily production and are bought and sold by the pound.

The government of Montana does not benefit financially from quota or quota transfers; rather, the state (through the Milk Control Board and Milk Control Bureau) acts as a rule-making body in deciding how quota transfers occur.

When quota was initiated, there was a penalty for transferring quota and not using it to discourage the collection of quota pounds and to keep price speculation to a minimum.

The price per pound of quota is not set by the state either and varies depending on supply and demand as producers exit the industry and others look to purchase more.

Because quota has a monetary value, it can be used as equity when taking out a loan, but any liens against the quota must be paid before it can be sold.

The total amount of quota that was set in 1989 and first implemented in 1990 was based on Class I utilization at that time and has not changed. Thus, the amount of milk considered “quota milk” has remained nearly constant for the past 23 years.

The following hypothetical example illustrates how quota changes the way farmers are paid for their milk:

John currently owns 10,000 pounds of quota. His daily production is 10,500 pounds. Because the milk is pooled, John is hopeful that all of the other dairy farmers are producing at a level that is very close to their quota so that there will not be much excess in the state.

At the end of each month, the Milk Control Bureau calculates how much milk was produced and compares that with how much milk went in to each type of processed product. Currently, it is about a 70-30 ratio, with the majority going to Class I fluid sales.

Therefore, the highest price John will receive for his milk will be for the 10,000 quota pounds produced, which will receive the pooled price of 70 percent Class I and 30 percent Class II or III.

The additional 500 pounds of milk he produced will get the lower over-quota price, which is always set at $1.50 less than the highest pooled price.

If John wanted to purchase additional quota pounds to fill his production, he could do that if there was some available. As soon as he owns it, John will reap the higher pay afforded to the portion of what he produces under quota.

National supply management plans have been brought forth many times over the years, with no clear answer on whether it would be a good match for the U.S. dairy industry.

The issue of managing supply continues to be discussed at the national level, with a recent vote to remove the measure from the farm bill.

Because little is known about how supply management affects dairy farmers in this country, the discussion about its pros and cons could use more background.

For my master’s research, I interviewed 17 dairy farmers across Montana to understand how quota may have changed their decision-making process for their dairy, specifically if it altered plans for adopting new technology or growth.

Part 2 of this article will cover the results of my study and possible lessons for the broader U.S. dairy industry. PD

Laura Ginsburg earned her M.S. from the University of Montana in 2013. She received a Fulbright scholarship to study dairy policy in New Zealand for 2014 and is also starting a small dairy in Montana.

PHOTO

Before the institution of quota, farmers typically held a shipping contract with a specific creamery for a certain amount of milk. If the farmer wanted to significantly increase his or her herd, they would have to contract with the creamery to do so. Photo by PD staff.