In late June, the first-ever U.S. Precision Dairy Conference brought together dairy producers that utilize each of the five robotic milking systems that are now commercially available in North America. Read about how they’ve changed their farms and management systems to adopt this emerging technology.

Click here or on image at right to view at full size in a new window.

Bradley Biehl

Corner View Farm

Kutztown, Pennsylvania

A fourth-generation dairy producer, Bradley Biehl partnered with his father, Dalton Biehl, to install the first U.S. Astrea 20.20 by AMS Galaxy USA. W

ith a bachelor’s and master’s degree in mechanical engineering from Penn State University, Brad designed a new fully automated facility around the two-stall robotic milking system.

This robot features a single robotic arm that milks cows in two side-by-side stalls.

Transitioning from a 60-cow tiestall operation, the farm doubled in size to 120 cows. With only adding a fraction of labor, the farm achieved a 30 percent increase in milk production.

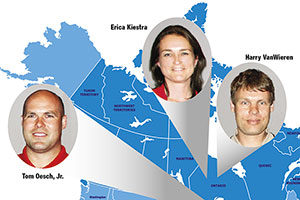

Erica Kiestra

Kie Farms, Ltd.

St. Mary’s, Ontario, Canada

Dirk and Erica Kiestra of Kie Farms are set up to milk 90 cows in an MIone automatic milking system from GEA Farm Technologies. One robotic arm services these two tandem milking boxes, which they hope to expand to a four-box system one day.

On average, the Kiestras’ cows produce 93 pounds (41 liters) of milk per cow per day, with the cows milking about 3.5 times per day.

At the end of June, they were only milking about 80 cows that averaged 80 pounds per cow per day, many of which were at 250 days in milk.

This is because they were gearing up to produce extra milk for the fall incentives through Ontario’s quota program in August and September.

Their low somatic cell counts average 60,000 to 65,000 for the herd.

Tom Oesch, Jr.

SwissLane Dairy

Alto, Michigan

Established in 1915, SwissLane Dairy Farms is a fourth-generation operation that includes six family partners. In total, SwissLane Farms includes 2,000 milking cows, 1,800 replacement heifers, 400 steers and 4,500 cropping acres.

In 2011, the farm built a robotic dairy for 500 cows one-half mile up the road from the main dairy. It includes eight single-box, single-arm Lely Astronaut milking robots, a freestall barn for milking cows, a manure lagoon and a dry cow facility.

Oesch, who worked as a dairy nutrition consultant before returning to the farm, oversees the robot dairy and provides nutritional support for the entire SwissLane Dairy operation.

The herd is averaging 88 pounds per cow per day at 2.8 milkings per cow. His goal is to get to 100 pounds per cow to be able to fill a truck in 24 hours.

Jake Peissig

JTP Farms

Dorchester, Wisconsin

When Jake Peissig returned home to farm, he and his father, Tom, built a robotic milking facility, located on a completely new site.

The 245 milking cows are housed in a cross-ventilated freestall barn with sand bedding, and separated into four groups, one for each of the four DeLaval VMS milking robots.

Labor was one of the main reasons they adopted the robotic technology, and now the Peissigs are able to operate their facility, including the raising of all youngstock, using only two full-time people.

Jake Peissig says he believes to maximize yields, one must maximize cow comfort. Milking 62 to 67 cows per robot, the farm consistently averages more than 6,000 pounds per robot per day or 95 to 100 pounds per cow per day.

Click here to read more about JTP Farms.

Harry VanWieren

Four Clover Dairy Inc.

Thedford, Ontario, Canada

Thirteen years after moving from Holland and starting a dairy in Canada, the VanWieren family decided to replace their double-10 parallel parlor with three single-box, single-arm MR-S1 BouMatic robots to milk their 140 cows. Average production is 69 pounds of milk per cow per day with 4.3 butterfat and 3.8 protein.

The barn has 150 freestalls bedded with mats and sawdust, and a straw-bedded pack for dry and sick cows. The old parlor is now an area for sick cows.

The family operation, including Harry VanWieren, his parents and his brother, currently owns 300 acres and rents 85 acres to grow hay and corn. In addition to family labor, a tractor driver is hired to haul wagons for haylage and corn silage harvests.

Why did you decide to install milking robots?

BIEHL: Our old facility was an outdated tiestall barn – the facilities needed updating. My father could not physically bend anymore to milk cows and was ready to sell the cows.

Robotic milking brought exciting technology to keep the next two generations interested in the business, keep the business viable and allowed my father to continue to care for cows – twice as many cows – with a fraction of the physical milking labor required and virtually no bending.

OESCH: It fit within our farm’s core values, which were established by my great-grandfather and great-uncles.

They are to behave with God-honoring conduct, focus on the cows, be light-years ahead, make hay while the sun shines and become productive people.

PEISSIG: To eliminate the need for additional labor and embrace technology. Since robots are modular, you can increase gradually instead of jumping from 500 to 2,000 cows. Plus, you never have to pull a drunk robot from out of the ditch.

What would you design differently if you could start again?

BIEHL: I would have made sure I did more planning and research on the differences in nutrition required to have a successful robotic herd.

We struggled for the first several months and only after partnering with (a robotic milking consultant) did we get the nutritional support needed to turn our herd from a struggling 60-pound herd to a thriving 84-pound herd today.

OESCH: We would move the robots closer together and closer to the scrape alley. I’d like better footing at the robot approach. I’d also consider having a separation area for special-needs cows at each robot.

We have K-flow robots (where cows enter and exit from the side), and I would like I-flow (where cows move straight through the unit).

What worked and what didn’t in your start-up process?

BIEHL: My biggest challenge was not having a nutritionist with experience in robotic milking. Once we made nutritional changes, everything turned around.

KIESTRA: Have lots of people and install a temporary training lane. Within a week, they all milked well.

OESCH: We started all eight robots at one time, which was good. When we started, we had 300 cows on a 500-cow farm.

This would have gone better with 425 cows because three months later we started calving all the purchased heifers, and I had to go through another start-up by myself. My advice is to start with as many cows as you can.

PEISSIG: You need a lot of people for three days straight. Don’t be afraid to hang extra gates and make chutes. Also, don’t get too hung up if some cows don’t get milked in 20 hours; they’ll catch on.

VANWIEREN: Lots of help and lots of gates. Only five months in, we’re still in some of the start-up process.

Are you culling or breeding differently?

BIEHL: We have 60 first-lactation animals, and we were pretty selective with those. We culled a few for cross rear teats when we were starting out.

KIESTRA: We did select on teat placement.

OESCH: We started with a pretty youthful herd and haven’t reached the point where we need to breed differently.

PEISSIG: The ideal cow would be a medium-framed Holstein. We have 2,200-pound cows going into the robot, and it’s a tight squeeze.

One big thing I look for is milking speed. I culled a cow milking 100 pounds a day because it took her 22 minutes each milking. At three times a day, she held up the robot for more than an hour a day.

VANWIEREN: We went straight from the parlor to the robots and only shipped one cow because she was too slow.

What is your opinion on forced or guided-flow cow movement vs. free-flow?

BIEHL: I explored all of the options from a practical and business perspective. There’s a complexity difference that translates into much lower capital costs for the free-flow system.

Maybe I fetch three or four more cows, but I don’t know if that is added labor because I’m going through the barn to groom stalls anyway.

KIESTRA: The parlor system to us is a forced system. I think (our guided system) flows freely. Our cows can move to different areas in the barn through sorting gates from their stalls. If they don’t go through often enough, we go check on them.

OESCH: We built a free-flow barn because I couldn’t visualize (the guided-flow) in my head. In my barn, about 5 percent of cows need to be fetched. Fetching cows to me is not a chore.

If the list is longer, the robot was probably down a long amount of time. No matter what you build, I don’t think there’s a right answer to this problem. The dairyman has to buy in to whatever system he puts in.

PEISSIG: I abide by the guided perspective. A guy in Pennsylvania once told me, “The cow can make whatever decision she wants, but when she does, it’s going to be in our favor.” I find it to be a way to maximize every cow’s yield potential and maximize yield from each robot per day.

VANWIEREN: We have a free-flow barn. I fetch five to six cows morning and night. I don’t see it as much of a chore.

What additional precision technology do you use?

BIEHL: We have programmable and iPhone-controlled lighting, curtains, sprinklers, fans and IP cameras.

KIESTRA: Robotic manure scraping, as well as automated climate control and the latest ventilation systems. Management tasks can be monitored remotely through an Internet camera system.

OESCH: Alley scrapers

PEISSIG: Automatic scrapers, smart gates into the milking area, automatic feed pusher

VANWIEREN: Alley scrapers PD

Karen Lee

Editor

Progressive Dairyman