The European Union first introduced milk production quotas in 1984. At the time, the EU was dealing with a major surplus of milk, and production quotas were just one of the tools utilized to rebalance the market.

The milk quotas were originally meant to expire after just five years, but various reforms allowed EU dairy producers to continue operating with production quotas for more than 30 years. In 2003, the decision was made to adjust and eventually end production quotas.

The date the quotas would end was March 31, 2015. Demand for dairy products had been rising, and EU producers would need the freedom to expand to meet that demand.

To provide a “soft landing” for producers before the quotas were removed, the European Commission allowed producers to expand at a specified rate, which devalued the quota over time. However, after seeing massive exports in 2013 and record-high milk prices in 2014, producers accelerated their expansion.

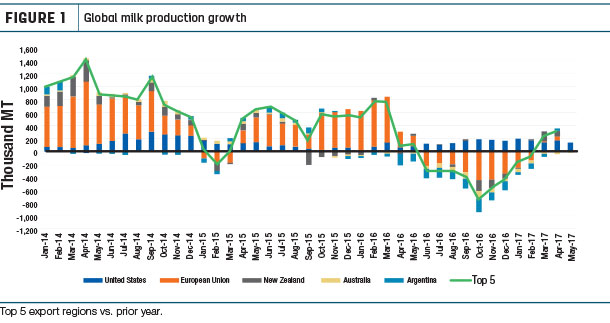

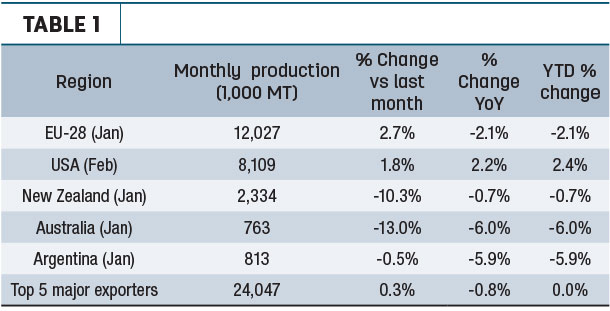

Production surged before the official end of quotas. In 2014, the EU saw year-over-year production growth as high as 8.2 percent. Once the quota program was officially retired, production continued growing, but the milk price began to fall. The weighted average milk price among EU countries fell by more than 36 percent from 2013 to 2016.

The export boom in 2013-2014 was highlighted by milk powders (whole milk powder, skim milk powder and nonfat dry milk). In the wake of this, a great deal of investments ramped up the production of exportable milk powders, in both the EU and the U.S.

Demand for milk powders has not been quite as robust as many would have thought, which has led to bulging inventories. Prices of dairy commodities in the EU fell to record lows, triggering the European Commission’s intervention program. From March to September each year, the European Commission can purchase a specific quantity of skim milk powder and butter.

In 2015, there were 40,280 metric tons (88.8 million pounds) of skim milk powder added to intervention program inventories. In 2016, the price of skim milk powder remained so low for so long the European Commission expanded the amount of skim milk powder that could be purchased several times.

By the end of 2016, there was an additional 334,551 metric tons (737.5 million pounds) of skim milk powder added to intervention program inventories. In an April 2017 release, intervention stocks were at 352,395 metric tons (776.9 million pounds). To put this in perspective, over the last three years the U.S. has produced an average of 2.263 billion pounds of nonfat dry milk and skim milk powder. That would mean the quantity in intervention is roughly 34 percent of what the U.S. produces annually.

Throughout this entire period, there have only been two tender sales of skim milk powder to move this product. The first was back in December 2016 when just 40 metric tons (88,200 pounds) were sold for €2,151 metric tons (approximately $1.04 per pound), and the second came in June of 2017 where 100 metric tons (220,400 pounds) was sold for €1,850 metric tons (approximately 95 cents per pound).

Since the price of EU skim milk powder and U.S. nonfat dry milk tend to move in tandem, these massive inventories have dictated some of the price fluctuations seen in the U.S. nonfat dry milk market over the past few years. If prices fall too low, the intervention program creates a level of price support, but as prices rise and those intervention inventories are tendered, market participants begin to feel there is a ceiling in the market.

Since 2015, Chicago Mercantile Exchange spot nonfat dry milk has remained relatively range-bound between 70 cents per pound and $1 per pound, which is in the bottom 40 percent of historical prices going back to 2005.

It was expected the removal of milk production quotas in Europe would lead to higher production, but the timing of it led to a result that exceeded the industry’s expectations. Can milk powders once again sustain long-term price support without the impending threat of the European Commission releasing intervention inventories on the marketplace? Probably, but it will take some time.

The European dairy markets have seen some immense volatility over the last few years. Luckily, the growth of dairy futures on the European Energy Exchange has been able to provide market participants with some of the tools needed to combat this volatility. While they may not be quite as developed as the dairy futures and options traded at the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, there is some excellent growth potential based on the needs of the market. ![]()

-

Curtis Bosma

- Account Manager

- HighGround Dairy

- Email Curtis Bosma